Interview,

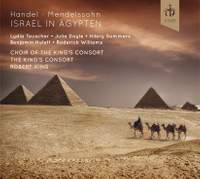

Robert King on Handel's Israel in Ägypten

Conductor Robert King has a particular interest in recreating historical performances - not merely restoring the ethos of authenticity, as so many conductors and ensembles now seek to do, but even homing in on specific events in musical history.

Conductor Robert King has a particular interest in recreating historical performances - not merely restoring the ethos of authenticity, as so many conductors and ensembles now seek to do, but even homing in on specific events in musical history.

His latest release continues this trend, with a look back at the very first stirrings of the period-performance movement in Felix Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn championed the music of Bach and Handel, and produced a version of the latter's great Old Testament oratorio Israel in Egypt - and it's this version, Handel seen through a Romantic lens, that has attracted Robert's attention.

I asked him how he approached this curiously paradoxical project - both authentic and defiantly inauthentic at the same time!

Hitherto your recordings have mostly been performances of early works from a historically-aware perspective – played ‘straight’ as it were. Where did the idea come from to record this curious mixture of a work (which, to some eyes, might seem to be the exact opposite of historically-informed!)

I’ve always relished the opportunity to reconstruct “an event”, rather than just give a concert. I especially love working in music-drama, whether that be in the opera house, or in creating concerts that give audiences more than just the music – indeed, two of our most popular concert projects still remain The Coronation of King George, and the Venetian reconstruction Lo Sposalizio. Mendelssohn is one of my absolute heroes: I’ve always loved conducting his music, because he writes wonderful melodies, has such a grasp of structure and is a genius at creating subtle orchestral colours. So any Mendelssohn project I conduct is always very special for me – indeed, the finest concert TKC has given in its 36 years was the final performance, in Lucerne, of our 2007 European Elijah tour: an absolutely unforgettable concert. All musicians have a huge amount for which to thank Mendelssohn: not just for being a fantastic composer, but for all the work he did during his lifetime in helping to restore Bach and Handel to their rightful prominence. So for me the opportunity to recreate Mendelssohn’s own recreation of Handel was unmissable.

The whole point of this album is to present an authentic performance of Mendelssohn’s version of Handel’s oratorio. But doesn’t that pose a huge paradox in terms of which performance practices you adopt – those in keeping with Mendelssohn’s time, or those of Handel’s? How did you square this circle?

This definitely is Handel as performed by Mendelssohn in 1833. Everything we do is intended to take us back to that 1833 Düsseldorf performance: approach, style, instrumentation, bows, strings, pitch, rubato, trills, portamento, string attack –add in a radically different score, including new movements, re-ordering, and a new (German) text and it really is a substantially different score. Pragmatically in any case, you couldn’t possibly start the piece with a pure Mendelssohn overture – one that Mendelssohn’s father held was his son’s finest – and then switch into eighteenth century style for the rest of the work. So, as is so often the case, the solution comes straight from the music: we just have to follow the trail.

The accompanying notes refer to there having been several pragmatic revisions to the work, mostly responding to the presence or absence of an organ for continuo use in the various venues in which Mendelssohn performed it. How did you decide which of these to incorporate into your recording?

This was a part of the two-year reconstructive process that especially pleased me, because it required a lot of gathering together of scraps of evidence, assimilating it, creating a “style bank” and then using my composing and arranging skills to fill in the missing gaps – but always using the existing evidence as my basis. Anyone who’s heard my arrangements of works by all sorts of composers, usually as an encore in a concert, will know that I relish writing and arranging music in all sorts of styles. I have a secret hope (well, not so secret any more!) that I will be let loose on a really big film score so that I can bring all those skills together. Enough fragments of Mendelssohn’s additions survive for me to form a “style bank” and then compose the lines that needed to be added. I ran a test at the early rehearsals for the project, asking highly experienced players if they could tell me where they thought Mendelssohn ended and King began: that no-one worked it out gave me quiet satisfaction that I had done my job – much as an art restorer will add in the missing sections of paint to an old master, and we won’t quite know where the master ends and the skilled craftsman begins.

Much scholarly ink has been spilled over the matter of Mendelssohn’s relationship with his Jewish heritage. Do you think there’s any significance in his choice of this particular work – telling, as it does, the story of the freeing of the downtrodden Jews from oppression by a foreign power – as a major restoration project?

Though Mendelssohn’s forebears were Jewish, Felix himself was brought up in a religiously open atmosphere, only later being baptised as a reformed Christian. The story line of Israel in Egypt certainly attracted him, but maybe more for its dramatic possibilities. How often do you get to work on a score that includes a swathe of plagues, depicting swarms of flies, a thick darkness, the slaying of all the first-born of Egypt, leaping frogs, hailstorms and more? It would be hard not to get excited by such dramatic possibilities.

What with the addition of the overture and the unmistakeably Romantic orchestration, how far do you think this counts as a separate work in its own right, rather than merely a version of the original?

The Overture is indeed nine minutes of superb early Romantic, pure Mendelssohn, with life and energy mixed with exquisitely shifting washes of instrumental colours. After that we meet an old friend, but one wearing such radically different clothes, and speaking with so wholly a new accent, that she is all but a new friend. Yet there still comes comfort from knowing that, under it all, we’ve been friends for a long time, so we don’t need to start from scratch.

What do you think Handel would have made of Mendelssohn’s take on his oratorio, if he heard it?

Handel is the greenest of composers, always recycling. He’d surely have been pleased to know that, nearly a century later, another great German composer would enthusiastically be reworking his work.

Israel in Ägypten is released on 23rd March 2016.

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC