Recording of the Week,

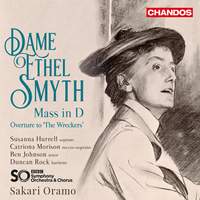

Ethel Smyth's Mass in D from Sakari Oramo and the BBC Symphony Orchestra

My Recording of the Week is an incredible album of two works by Ethel Smyth (1858-1944) which turned heads when we first played it in the Presto office – the overture to her opera The Wreckers, evoking a distinctly Poldark-esque world of Cornish smugglers, shipwrecks and romantic complications, and her hour-long Mass in D, which is nothing short of epic in its scope.

The overture, naturally enough, opens the album – a dramatic beginning, worthy of the silver-screen swashbucklers that would captivate audiences a few decades later, a middle section by turns pensive and ominous, and warm hymn-like sections. It’s very much in the tradition of the overture as a medley introducing the main themes of the ensuing opera. This brief overview is not to disparage it as insubstantial; rather, it suffers simply by being placed in the shadow of the majestic Mass in D.

The overture, naturally enough, opens the album – a dramatic beginning, worthy of the silver-screen swashbucklers that would captivate audiences a few decades later, a middle section by turns pensive and ominous, and warm hymn-like sections. It’s very much in the tradition of the overture as a medley introducing the main themes of the ensuing opera. This brief overview is not to disparage it as insubstantial; rather, it suffers simply by being placed in the shadow of the majestic Mass in D.

The Kyrie emerges out of mysterious darkness, rising to forceful heights and establishing a similar musical language to that of Beethoven’s dramatic Missa Solemnis. Smyth makes great use of insistent melodic lines scored in powerful octaves, with the BBC Symphony Chorus’ sopranos and tenors having their top As put to the test. Contemporary male detractors noted this trait disapprovingly – criticising Smyth for demanding, rather than beseeching, Divine mercy. A minority of well-meaning critics did shower praise on the composer for exactly the same qualities, however – believing her to have successfully jettisoned femininity and produced a work they dubbed “virile”.

Smyth follows the practice – rare today but relatively common under older Anglican liturgical uses – of placing the Gloria at the end of the Mass. The exultant, rushing opening of her Credo, though, is so evocative of Beethoven’s Gloria that one could be forgiven for doing a double-take and checking the track-listing! Some real hair-on-the-back-of-the-neck moments here; Smyth responds to the text identifying God as Creator with a thrilling and majestic climax on “facta sunt”.

It’s frequently remarked that composers of wavering, dubious or no faith at all seem to find no difficulty responding to the profoundest aspects of religious expression; one thinks of Howells, Brahms and others falling outside the boundaries of the conventionally religious. Smyth’s quietly awed setting of “et homo factus est” for the full choir, sotto voce and accompanied by sombre low brass, is a perfect example of this – she may never have regained her faith but her intense response to the Mass text seems to show all the passion and commitment of the most zealous believer.

It’s frequently remarked that composers of wavering, dubious or no faith at all seem to find no difficulty responding to the profoundest aspects of religious expression; one thinks of Howells, Brahms and others falling outside the boundaries of the conventionally religious. Smyth’s quietly awed setting of “et homo factus est” for the full choir, sotto voce and accompanied by sombre low brass, is a perfect example of this – she may never have regained her faith but her intense response to the Mass text seems to show all the passion and commitment of the most zealous believer.

Eschewing the common cliché of deploying the choral upper voices as ersatz angelic hosts, Smyth has the mezzo-soprano soloist (here a magnificently warm Catriona Morison, displaying the same qualities that won her the Cardiff Singer of the World competition in 2017) open the Sanctus with a sensitive line that evokes shades of Mahler or Duruflé. It’s again backed by quiet low brass – seemingly a favourite sonority of the composer’s, and a very effective one. Soprano Susanna Hurrell’s moment to shine comes in the Benedictus, with a sense of serene, almost pensive, weightlessness that is only briefly punctuated by moments of transition and moments of revelation. Scrupulously evenhanded to her soloists, Smyth turns next to the tenor to open the Agnus Dei; Ben Johnson’s beseeching tone, of which we had a preview in the Credo, is just as effective here, though his pleas for mercy now strike a more impassioned, almost urgent note.

Following this, the grand finale at last arrives in the form of the Gloria – more dazzling D major sunlight (and more heroic top As for the singers, whose tireless physical endurance here is really very impressive and merits a mention in dispatches). In the more subdued mid-section, baritone Duncan Rock finally has his turn, in solo and duet passages once again calling on Jesus to have mercy on humankind. If he lacks some of Johnson’s urgency, he makes up for it in presence; indeed Rock’s tones are so rich, so assured that he can’t quite convince as an imploring, sin-wracked supplicant.

It will come as no surprise that, after this, Smyth rolls up her sleeves for an unambiguously positive conclusion; those Beethovenian choral octave doublings are back for one more curtain call, and with the aid of an unusually generous percussion section (how many other Mass settings feature the side drum and triangle?), organ, orchestra, soloists and choir bring proceedings to a triumphant close.

Over the past few months, I’ve had the sensation that efforts to promote the works of female composers (both living and historical) have at last reached a critical mass – if you’ll pardon the pun – and gained a crucial level of momentum. This recording should by rights be front and centre in those initiatives; it’s a magnificent, uplifting work that, while far too large for liturgical use, deserves to become a regular of the concert-hall and choral-society repertoire. An exhilarating musical experience, not soon to be forgotten.

BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Sakari Oramo

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC