Interview,

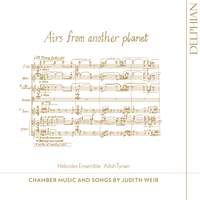

Judith Weir on Airs from Another Planet

A new album by Scotland's renowned Hebrides Ensemble showcases the music of Judith Weir for both voice and instruments; built around a reimagining of Scottish folk traditions but taking in contemporary African poetry and the immortal hymn-writing of the twelfth-century St Hildegard of Bingen, it's a dizzying whistle-stop tour of the boundless inventiveness of one of today's greatest living composers.

A new album by Scotland's renowned Hebrides Ensemble showcases the music of Judith Weir for both voice and instruments; built around a reimagining of Scottish folk traditions but taking in contemporary African poetry and the immortal hymn-writing of the twelfth-century St Hildegard of Bingen, it's a dizzying whistle-stop tour of the boundless inventiveness of one of today's greatest living composers.

I spoke to Judith about some of the influences that went into this album.

This album takes its name from the final set of pieces, the four Airs from another Planet in which you project Scottish folk traditions forward into the future to see what they might evolve into. Can you tell us anything about your compositional process here – how did you decide what elements to develop, and what to do with them?

This is an old piece, written over 30 years ago, so it’s a rather old-fashioned view of the future (!) I would describe the basic technique as ‘refraction’ of pre-exisiting tunes, for instance by harmonising them at the 4th and 5th simultaneously, often in extreme registers. And of course these tunes have been rewritten, particularly with the addition of very fast ornamentation, so as to be largely unrecognisable in the first place.

The Really? triptych from 2002 looks at first glance like three unconnected settings, whereas the other groupings recorded here are all unified by a clear common idea – is there an underlying theme to Really? as there is for the other sets on the album?

One simple connection that the texts from J P Hebel and the Brothers Grimm come from the same period of German literature and feature the same folk-like, sometimes absurdist, wisdom. Originally these three settings formed my lecture notes for a seminar about musical narrative. The first (about transport by donkey) requires the vocalist just to speak ‘naturally’. The second (concerning a kind of nuclear explosion featuring porridge) requires heightened speech moving via sprechstimme into operatic-style vocalism. The final song (about the concept of infinity, explained in a folk-like way) is simply a song, using the ‘normal’ singing voice.

Nuits d’Afrique is in part a response to Ravel’s Chansons madécasses of 1925/6. That group of songs famously included controversially sensual elements and a middle movement starkly warning fellow Madagascans to be wary of the motives of white colonisers. Was the choice of more “wholesome”, safer texts for your own Nuits of 2015 intentional?

The problem with the Ravel texts is that sentiments about male gratification and female submission (in movements I and III) are inexplicably shoved into the mouth of a soprano. I don’t at all recognise the backhanded description ‘wholesome’ and ‘safe’ about the rich and vivid poems by contemporary Francophone women writers from Senegal, Congo and Ivory Coast which form my own cycle.

Several of the pieces recorded here are instrumental responses to textual stimuli – the three chorales and O Viridissima are all pieces that might more often have taken the form of choral motets. How do you approach the idea of “setting” words in the absence of a voice to pronounce them?

O Viridissima and O Sapientia (the third of the Three Chorales) are freely based on Hildegard of Bingen melodies. But the Hildegard originals are highly melismatic, so it didn’t seem a big step to give these melodies to a cello or violin. The first two Chorales are not based on pre-existing material. They respond to the psychological and dramatic feel of two well-known hymn texts: Angels bending near the earth (golden and floating) and In death’s dark vale (dark and anxious, while bravely forward-moving.)

Given how much of the classical world looks back – not without reason – to the past for clues to help shape its identity, do you think the future is an untapped vein that might provide just as much inspiration if approached thoughtfully?

Speaking on behalf of composers – if that’s possible - nearly all of us are always looking to the future, trying to create music which will last a long time, and not lose its relevance or usefulness. Writing music (or literature) about some imagined future might soon become out-of-date once the era of that future is actually reached.

Ailish Tynan (soprano), Hebrides Ensemble

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC