Interview,

Michael Collins on his dual career

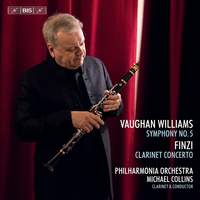

Michael Collins is no stranger to directing concertos from the clarinet, both on the concert-platform and in the studio, but his debut album on BIS (released earlier this summer) sees him taking things a step further and conducting his ‘old’ orchestra the Philharmonia in Vaughan Williams’s Symphony No. 5 – his first foray into purely symphonic repertoire on disc.

Michael Collins is no stranger to directing concertos from the clarinet, both on the concert-platform and in the studio, but his debut album on BIS (released earlier this summer) sees him taking things a step further and conducting his ‘old’ orchestra the Philharmonia in Vaughan Williams’s Symphony No. 5 – his first foray into purely symphonic repertoire on disc.

We’re very grateful to Michael for taking time to speak to us about his gradual realisation that conducting is ‘all about psychology’, the maestros who inspired him during his years as an orchestral musician, and his long-term plans with BIS in both of his capacities – especially as our conversation took place right in the middle of his recent house-move!

Photo: Benjamin Ealovega

What kickstarted your interest in pursuing conducting?

I suppose I can pinpoint one particular piece, and that’s the Mozart Clarinet Concerto. I’ve played it so many times in my life, and I got to the stage where I was a bit sick and tired of doing it with conductors who perhaps didn’t have the time or inclination to give it the justice it deserves - it often gets a quick run-through at the last minute, and then they move onto the Mahler symphony or whatever’s in the second half, so I thought ‘If the conductor wants to take it easy before Mahler 5 I’m happy to direct the Mozart myself’!

At the time I was doing quite a lot with the Academy of St Martin in the Fields, and with them I didn’t have to turn round and conduct at all: the director Ken Sillito would be leading from the violin, so it was just a matter of standing there doing my bit. But as I went round doing a similar thing with other orchestras people started suggesting I could actually conduct the tuttis, so it was a gradual process. Then I started doing whole programmes with orchestras like the South Bank Sinfonia, working with young musicians and having the opportunity to learn the trade as we were going along, and not long afterwards I got the position with the City of London Sinfonia and we went through a lot of the chamber orchestra repertoire together.

And the more I did, the faster I learned that it was all about psychology, about the relationship with the musicians, which is exactly what I wanted when I was sitting in orchestras myself: I played clarinet with the Philharmonia and the London Sinfonietta for a lot of years, so I’ve been on the other side of the coin and knew that what you really want is a conductor that’s on your side and can coax the best from you, not a them-and-us situation. Eventually I started doing the odd concert of bigger orchestral works in places like China and Brazil to see if it was going to work for me; again it was a natural progression, rather than me setting out my stall to do a big symphony. I learned to project my own wishes on a much larger scale without dictating them – so I suddenly found myself having to be more willing to show what I wanted rather than telling them outright. And it seemed to work!

Were any of the conductors you worked with at the Philharmonia particularly inspiring?

I can name the ones who were my absolute heroes at the time. One was Carlo Maria Giulini: he was a musician’s musician, and a gentleman. I remember turning up to the Festival Hall early for a Beethoven Nine, and as I was fiddling with my reed in the empty hall I saw this figure wearing a cape materialise at the side of the platform; I was slightly awestruck, but he came over to me with a cheery ‘Ah good morning, Mr Collins!’. I was taken aback that he even knew my name, but he sat with me and discussed the solo in the slow movement - where I wanted to take a breath, how I wanted to shape certain phrases, so that he could be absolutely with me. That for me was the icing on the cake of my time with the Philharmonia, because what a marvellous human being he was – he took the time to mould phrases with you rather than either dictating or leaving you to your own devices, so that for me was very special.

Another one was Evgeny Svetlanov, who could really take the paint off the walls in the Festival Hall in Rachmaninov or Tchaikovsky: he didn’t speak a word in rehearsals (though he’d have an interpreter there who would occasionally say something), and often he didn’t even play through a piece before the performance! But then in the concert he would just take the roof off, and I haven’t come across that electricity since then – I don’t want to sound like an old fogey, but music-making has changed in that respect. In my opinion, it’s all become about the glamorous side of things rather than the music itself being the driving force, but when I’ve play-directed larger works (like Britten’s unfinished concerto), I have found that some of that old electricity kicks in again: every single player sits up and takes part, whereas with a conductor they might lean back and coast. Particularly in bigger string-sections, the default mindset is that the responsibility comes from the front and filters back whereas in a situation like this they all have to take responsibility – it’s large-scale chamber music, and some of the results have been astonishing. It’s more difficult without question, but when it works and you’ve got every single player playing their heart out and taking ownership it’s quite wonderful.

Did you work with anyone on stick technique or did it come naturally?

I didn’t, though it’s been on my mind! I’m a fast learner, and I’d like to think that I know what musicians need, so whilst I’m never going to have the greatest technique in the world I can project what I want through my hands - I don’t use a baton, because that would get in the way. The other, practical reason for that is that if I’m playing a concerto later in the concert I can actually warm up my hands during the overture, whereas if I had a baton I’d have to reshape my fingers over the clarinet keys in a two-minute gap, which isn’t ideal!

You recorded the Finzi concerto less than ten years – why did you want to revisit it so relatively soon?

It’s a really basic answer, but an honest one! This is actually my third recording of the piece: my first was 38 years ago, with City London Sinfonia and Richard Hickox, and that was the very first recording I ever made. Then I did it again with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and I am really happy with it…but to get down to brass tacks the Finzi is a very popular piece with Classic FM, and they aren’t allowed to play my recording because it’s with a BBC orchestra, which I thought was a shame! My Mozart recording with the Swedish Chamber Orchestra is on Classic FM virtually every day, and the Finzi is just as popular, so I decided to do another version with my old orchestra that will actually get some air-time!

Why did you choose to couple it with Vaughan Williams's Fifth Symphony?

I was thinking outside the box in a way when I came to do this first recording with BIS: I didn’t want to do the Finzi with another clarinet concerto, so it was as pure and simple as choosing one of my favourite symphonic works. Of course there is this very pastoral quality to both pieces, so I suppose there’s a link in that respect, but the real connection was just that these are two works I adore. These days it’s so easy to go down the path of clever concepts, and sometimes we forget that we are human and just want to document whatever is in our heart at that particular time. I’ve never thought of myself as old-fashioned, but as the years go on the more I feel that I will stick to my principles and do something that I believe in rather than something clever just for the sake of it – I’m a bit of a rebel in that way, but I’ve got a few miles on the clock so I’m going to stick to my guns!

What’s next in terms of your collaboration with BIS?

I’ve actually just done another four recordings! One’s the Brahms sonatas (again!) with Stephen Hough; we recorded the Brahms trio with Steven Isserlis for BMG years ago, and have been doing the sonatas in concert together for decades. We’ve known each other since the 1978 BBC Young Musician of the Year, when we were both finalists, so we’re exactly the same age - I think there’s just a month between us. We did the Brahms sonatas about a month before lockdown at Wigmore Hall as part of Stephen’s residency, and said ‘Wouldn’t it be great to record?’. Again, no reason: it just felt right. Then I did a French recital-disc with Noriko Ogawa, and then last week a trio recording, which included some repertoire I hadn’t recorded before – the Mozart Kegelstatt, Schumann’s Märchenerzählungen, Stravinsky’s A Soldier’s Tale, and Bruch’s Eight Pieces for Clarinet, Viola and Piano. And we’ve got the Schubert Octet coming up. Further ahead, there’s another project which I shouldn’t really talk about…but let’s say it’s the complete works of a certain composer which will run to 30-odd CDs by the time it’s finished, and it hasn’t been done since the 90s… It’s been my passion to do this for years, and I’ve got the green light now.

What else is on your hypothetical conducting wish-list for symphonic repertoire?

Two main things. I adore British orchestral music, probably just because of my background: I’d like to cover all the Vaughan Williams symphonies, but I want to do more unusual British repertoire too. I’d also love to get my hands on some Shostakovich and Rachmaninov symphonies: music is a universal language, and I think we’ve got over this attitude of believing that only Russians can conduct Russian music and the Berliners and the Viennese can’t play Elgar! But we’re not built to cover the entire spectrum of music and feel comfortable with all of it. I know at this stage in my life that I wouldn’t feel comfortable doing Strauss and Wagner – I love it, but there are plenty of people out there who have a voice and opinion on that music, and that isn’t me. But I do feel that I have a voice for British and Russian repertoire, so that’s my dream.

Do you feel your perspective on music-making has altered at all in lockdown?

In a way, it’s been a chance for our profession to press the reset button, because I do feel it was getting slightly out of control, if I’m honest! I mentioned the glamour aspect of the industry earlier, and I think a lot of that might fall away now: people will want music for its own sake, played really beautifully, not by a certain player that’s in it for celebrity and international travel. It’s been a difficult time, but I do hope that the profession has learnt something from the past few months.

Michael Collins (clarinet/conductor), Philharmonia Orchestra

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC