Interview,

Sir Mark Elder on Donizetti's Les Martyrs

Following a highly acclaimed concert-performance at the Royal Festival Hall last November, Donizetti's first great French success-story Les Martyrs will receive its first outing on disc next month courtesy of Opera Rara, Sir Mark Elder and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, and a stellar cast including soprano Joyce El-Khoury and tenor Michael Spyres.

Following a highly acclaimed concert-performance at the Royal Festival Hall last November, Donizetti's first great French success-story Les Martyrs will receive its first outing on disc next month courtesy of Opera Rara, Sir Mark Elder and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, and a stellar cast including soprano Joyce El-Khoury and tenor Michael Spyres.

Based on a 1642 play by the great French tragedian Pierre Corneille (which tells of the conversion to Christianity and eventual martyrdom of an Armenian nobleman, Polyeucte, at the hands of the Romans), Donizetti's Italian opera Poliuto was completed in 1838 for the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, but was banned by the censors at the eleventh hour after the King of Naples decreed that the suffering of Christians was not an appropriate subject for the stage. Undeterred (if understandably rattled!), Donizetti promptly upped sticks and relocated to Paris, where he proceeded to refashion the piece into a four-act grand opera for the city's major opera-house.

I spoke to Sir Mark over the phone on Saturday to find out a little more about Donizetti's 'visions and revisions', his immersion in the Parisian opera scene of the 1840s, and his development of a specifically French voice in Les Martyrs…

Poliuto itself is hardly one of Donizetti's better-known works, but why is Les Martyrs only now receiving its first proper outing on disc?

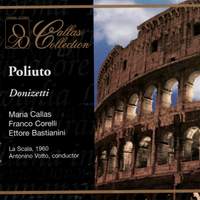

Poliuto’s fame rests on a recording made in the 1960s with Callas and Corelli, which is a bowdlerised version…Poliuto wasn’t known because it wasn’t performed (Les Martyrs was performed first, in Paris) and so it wasn’t really published and known until after Donizetti’s death…When Poliuto was discovered, people got excited by its very tightness - it’s a very taut piece that had been written for an Italian audience – but then they realised some of the best bits of Les Martyrs weren’t in it! Callas took this trio, and plopped it into Poliuto because they didn’t want to miss it.

There’s never been a proper edition of either of these two pieces till now. Because Poliuto is generally known to be a good piece, and the Callas version existed , we thought it was high time that we should do a new edition of Les Martyrs and present this French opera in its own right, in a properly rehearsed and recorded studio performance. And it’s completely unknown: everybody says ‘Oh he did a version in French to please the French public, and Poliuto is the more important piece’. I’m absolutely convinced that that’s not the case.

How did Donizetti feel, do you think, about reworking the score – did it give him free rein to explore and expand, or did it involve certain compromises?

I don’t really think of them as compromises – what he needed to do was to make a French success, and this was the first time he’d ever had a chance to write a piece for the very large Paris Opera, the Académie Musique. (There have always been a number of opera houses in Paris and some of his earlier operas were already well known in these smaller theatres, but they were smaller-scale pieces). If you were to write a piece for the main Paris Opera, you then had to conform with the taste of the day, and the most obvious thing is that you have to include a substantial ballet (and it HAD to be in the second act!), because the public would expect that.

But there were other things that the Paris public were known to want, and in order to make a success he had to adjust his style. It wasn’t that he was writing something that he’d always wanted to do: it was ‘If I’m going to do this, and they’re going to realise that I’m a composer of substance, I’ve got to understand the style of what they like…’. Now the French audiences rather despised Italian vocal bravura, so he had to take a lot of that out. There is one great passage of vocal brilliance, which is a cabaletta for the soprano, and he kept that in, because it was a display for this very famous French singer [Julie Dorus-Gras]. But generally speaking the text is set very clearly: there are some cadenzas from time to time, but the audience expected to understand the poetry, and this is particularly important because he had deliberately chosen as the libretto a famous French tragedy (Corneille’s Polyeucte) and so he had to respect that so that people would think that this famous Italian composer had done right by a French tragedy. In order to make it fit Parisian taste he had to make it into four acts - he could’ve done five, as French Classical tragedy is written in five, but he settled for four, and he had to expand the work. He did this in various ways apart from writing this long ballet, including creating another role, a role that in Les Martyrs (the father of the female character – in French ‘Felix’) becomes an enormously significant basso cantante role, whereas in Poliuto it was a tiny comprimario part.

The new title, Les Martyrs, suggests that the reworking places more emphasis on two central characters (Polyeucte and Pauline) rather than one – is this shift reflected in the revised score?

No: the choice of the title was simply because it would have seemed presumptuous to call it Polyeucte, because that was such a well-known title for the original Corneille play…he wanted to say that in turning it into a French grand opera that the libretto was based on this famous play, but that people who knew Polyeucte - and still do now – shouldn’t come along and think it was a straightforward re-telling. This was going to be a grand opera, with all the paraphernalia of grand opera, and so he decided that he’d better have an alternative title!

Was Donizetti writing for specific singers, and for a different cast from the original Naples one?

One of the most extraordinary and unusual facets of these two works is the writing for the two tenors; both of the tenors concerned with the creation of these operas were French. One was Adolphe Nourrit, who was a star in the early 1830s in Paris and was a remarkable singer. He was an extremely sensitive man, rather uptight, and when Gilbert Duprez [who eventually created the role of Polyeucte in Les Martyrs] arrived and really usurped his position and the public took him to their hearts, Nourrit thought that he’d leave Paris and let Duprez get on with it. And he went to Naples and talked to Donizetti about making an opera specially for him that would give him a great role that he could take up and down the Italian peninsula, so that while he still had voice he could have an Italian career. That’s how Poliuto came to be born …And also because Nourrit knew the place so well, he could talk to Donizetti and tell him how to turn it into an opera [for Paris] - so Nourrit was very much part of the original plan for Poliuto. When the King of Naples said ‘You can’t show Christians suffering on the opera stage, this work should not be performed – it would be a gross ethical mistake’, it was all written, it was all ready to go, and it was forbidden; and Nourrit saw his chance of having an Italian career disappearing, and he committed suicide, threw himself off the top of a building.

So, when Donizetti set about turning it into Les Martyrs, he knew that he had this great success-story in Paris (Duprez) as the principal singer, and he tailored the part in Les Martyrs to Duprez’s talents. In fact if you compare just those two roles, you’ll see how much he altered it. But he altered all the parts, because he knew who the singers were – they were tailor-made. Donizetti by then had spent time in Paris already and knew the scene.

How influenced was Donizetti by the musical language of operas like Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots and Halévy’s La Juive, which had opened in Paris a couple of years earlier?

Completely. I’m sure that (just as Verdi did years later in Milan) Donizetti realised it was the only way to be: you needed to know what the public were responding to…and I’m talking about chords here, not melodies. Harmonic progressions, writing for the orchestra, how to feature the orchestra….Very interestingly for me (as I’m an ex-bassoonist) Les Martyrs begins with a concerto for four bassoons - and this couldn’t possibly have been written for an Italian opera orchestra, where you’d be lucky to have two! But since the baroque period, the French had always had four bassoons, because the French bassoon was a softer-grained sound, and Rameau and his generation always wrote for four bassoons and that went on and on (and not just Donizetti, it was Berlioz, and Verdi in Don Carlos), so he highlighted the four-bassoon idea by starting this huge grand opera with an intimate, rather plangent section for this unexpected colour, and that’s just one example!

Given that Les Martyrs was initially so well received, why do you think it fell out of the repertoire relatively quickly?

Because Duprez went elsewhere! They didn’t have a person they could put on when he wasn’t available (indeed the first night was postponed because he was ill), and that’s the problem with writing a piece specially for somebody - if they’re not available, you then have to make alternative arrangements. The person they put on instead of Duprez was no substitute, and so the public weren’t very interested in the piece without its star.

Donizetti was writing opera buffa at the same time as working on Les Martyrs: do you detect any slippage between the two genres, or does he sustain the grander, tragic style throughout?

I think he does [sustain the grand style] completely. He juxtaposed opera buffa and melodrama all through his life…, and had this incredible Protean ability to turn his hand to all sorts of style. I think by the time he got to turning Les Martyrs into a success he was a master, an absolute master: the richness of the score is extraordinary, the excitement of it, the way he builds it up, the way each scene has a great sense of architecture. I think it’s a much greater achievement than Poliuto - although Poliuto is very remarkable - and I think if they do Poliuto well at Glyndebourne this summer, and our recording comes out at the same time, it’ll be very, very interesting to have the opportunity to compare both pieces.

Can I press you for one or two personal highlights from the score?

(I’m hesitating here because there’s so much choice! It’s so rich, there’s so much variety!)... I think that the scene at the end of Act One when Pauline discovers that her beloved, her husband (and that’s one of the interesting things about the story…operas are very rarely about husbands and wives, they’re usually about people who WANT to be husband and wife!), she finds out that he’s already secretly become a Christian and betrayed his religious upbringing, and their confrontation, surrounded by fellow Christians, is very strong. It evolves into the most beautiful trio for soprano, two tenors and a little chorus, with which the first act ends. And in expanding the form of the opera, Donizetti needed to make a new finale to the first act and his solution is to do something lyrical and extremely beautiful, and the voices weave round each other in the most beautiful and inspired way.

One of the special qualities of the recording that we’ve made is to include some passages that were taken out before the premiere, and have consequently never been heard before, and we’ve included them in the passage of the opera, rather than as appendices (which is often what we do at Opera Rara). In this instance the flow of the opera needs to be maintained, and these three passages are of such good quality that we thought it might be exciting to include them, and in the second act the arrival of the baritone, Sévère, there is a long aria which is interrupted by this scene in a style of brave and original daring. The tempi, the drama here is so strong that it’s like it’s 30 years later, and this first scene with Sévère is remarkable, very, very exciting.

And the other instance I would give is the whole of the second scene of the third act - which is the climax of the drama in a way, because it’s the scene in which Polyeucte decides to stand up against his Roman background and comes to this great formal occasion that has been organised to celebrate the arrival of the Roman consul Sévère, and he literally pushes over the Roman gods, he denounces them, he admits that he’s become a Christian. And of course in doing this he’s committing suicide, but he decides to be proud of his new faith and to mock and scorn the Roman gods, and the scene that results from his foolhardy passionate spontaneity is one of the greatest scenes that I think Donizetti ever conceived - the way that the music supports that drama and finishes with a big ensemble involving the whole company in music of incredible energy and originality…I think it’s very special.

Currently available as a download, the Callas-Corelli recording mentioned above dates from 1960 and is conducted by Antonino Votto.

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC