Interview,

Ian Venables

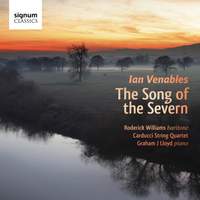

The Liverpool-born composer Ian Venables turned sixty last month, and after enjoying his recent disc The Song of the Severn (released in June on Signum) I thought it was high time we found out a little more about a composer who's widely acknowledged to be one of today's great champions of English art-song: his responsiveness to text (he's also a literary scholar, having published on the poetry of John Addington Symonds) and gift for melody have ensured that his settings of English poetry have attracted some of the finest British singers of the day, including Roderick Williams, Andrew Kennedy, Allan Clayton and Daniel Norman.

The Liverpool-born composer Ian Venables turned sixty last month, and after enjoying his recent disc The Song of the Severn (released in June on Signum) I thought it was high time we found out a little more about a composer who's widely acknowledged to be one of today's great champions of English art-song: his responsiveness to text (he's also a literary scholar, having published on the poetry of John Addington Symonds) and gift for melody have ensured that his settings of English poetry have attracted some of the finest British singers of the day, including Roderick Williams, Andrew Kennedy, Allan Clayton and Daniel Norman.

I first came across his music nearly ten years ago, when four of his songs appeared on Roderick Williams's Severn & Somme, alongside music by Ivor Gurney (with whom Venables has strong links, having chaired the Ivor Gurney Society and orchestrated and edited several of his works), and this new disc shares many of the features which captivated me about that earlier recording...I spoke to Ian earlier this week about the Worcestershire landscape which inspired works on both discs, and about writing for the voice of Roderick Williams, who gives the recording premieres of two major song-cycles on The Song of the Severn…

How do you go about creating that specific sense of place in your music? Does it spring from your choice of texts, references to folk-songs (or other compositions associated with the area), or from something altogether more ephemeral?

As with all of my songs the music flows out of the words. In ‘The Song of the Severn’ I chose poems that were rooted in the Worcestershire landscape. They all evoke a ‘sense of place’ and conjure up images of rural life, past times and most importantly, its people. Each of the five settings inhabit a different sound world and have a specific narrative, whether it be, the Romans besieging an ancient British hillfort up on the Malvern Hills or a reflection by the poet John Drinkwater after his visit to Elgar’s grave. My music comes as a response to the poet’s vision and I hope that through the cycle I have been able to capture something of the spirit of the Worcestershire.

Would you agree that there’s a tendency today to see pastoral (both in music and literature) as a nostalgic, even antediluvian genre? How much does your music make use of what Peter Marinelli called the ‘art of the backward glance’ in terms of on earlier models of pastoral in English music?

Firstly, I think that the term ‘Pastoral’ has become a rather overused and somewhat misleading term. By my understanding, English Pastoralism is ascribed to the kind of music written in the early part of the twentieth century that was based upon English folk song. Examples, might include Vaughan Williams’ Norfolk Rhapsodies or Delius’ Brigg Fair. Beyond this, English music in the twentieth century evolved along quite independent lines. Although, I do enjoy English pastoral music I don’t feel that it has informed my own music. On the contrary, my music follows in the wider development of English twentieth century music, although I would be the first to admit that it is nourished by this tradition. If this is what Peter Marinelli means by the ‘art of the backward glance’ then perhaps he’s right.

Roderick Williams has particular form on disc when it comes to English song of earlier generations (I’m thinking particularly of his Finzi, Quilter and Vaughan Williams on Naxos) – were these cycles written specifically with his voice in mind?

Both, ‘The Song of the Severn’ and ‘The Pine Boughs Past Music’ cycles were written for Roderick Williams. Indeed, he gave both of these cycles their first performance. I have worked closely with Roderick over many years and I did have his voice firmly in my mind when I was composing these works. Roderick is an amazingly versatile and expressive singer. On the one hand, he can effortlessly sing hushed long breathed lines, whilst on the other he can produce incredibly powerful forte notes at the top of his tessitura. Needless to say, I exploited these wonderful qualities to the full!

One more specific question: all of us in the Presto office were struck by the melodic echoes of Danny Boy in ‘Midnight Lamentation’ – was this a conscious reference, and if so what was it about the text that set you on that track?

The ‘melodic echoes’ of Danny Boy in ‘Midnight Lamentation’ have been pointed out to me before. Although, I cannot be certain, I doubt that I would have known this song when I composed it in 1974 when I was only 19 years old. It was certainly not a conscious reference. However, I do remember writing the song very quickly and the music came quite naturally in response to the highly emotionally charged words. As with Vaughan Williams, I think that any folk song resonances are hopefully distilled by one’s personal voice and musical style.

Finally, what are you working on at the moment? Will you be continuing in the pastoral vein or moving further afield?

I’m currently working on a song cycle, for tenor, viola and piano to commemorate the Great War.

This work, entitled, ‘Through These Pale Cold Days’ - Five Songs of War and Remembrance, and they will be given their in Worcester next year at a concert programmed to coincide with a civic event to commemorate the Battle of the Somme. The texts I have chosen are all by First World War poets and include poems by Owen, Rosenberg, Vincent-Morris, Sassoon and Studdert Kennedy.

You ask whether my music will be continuing in a ‘Pastoral vein’ or moving further afield? As I hope I’ve explained in an earlier answer, I do not believe that my music is written in a pastoral idiom. My musical language is basically tonal and melodically driven but I frequently use dissonance and that this dissonance can be at times harsh and uncompromising. For example, in my setting of Housman’s ‘Easter Hymn’ -the first of my ‘Songs of Eternity and Sorrow’ cycle. Of course, given the subject matter of my new song cycle, the music I am currently writing is much darker than usual. It is certainly inhabiting a more dissonant and plangent sound world. Having said that, the music does have affirmation, and I hope that by the end of the cycle it is this response that the listener will take away with them.

Photograph of Ian Venables (c) Graham Wallhead.

'The Song of the Severn' was released last month on Signum.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC