Interview,

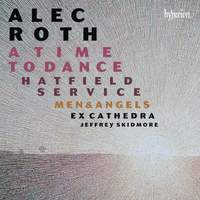

Alec Roth - A Time To Dance

British composer Alec Roth has a distinctive and uniquely accessible musical voice, above all in his choral music (though his oeuvre extends right across, and indeed well beyond, the classical sphere - with a more than passing interest in the Indonesian gamelan feeding into his style).

British composer Alec Roth has a distinctive and uniquely accessible musical voice, above all in his choral music (though his oeuvre extends right across, and indeed well beyond, the classical sphere - with a more than passing interest in the Indonesian gamelan feeding into his style).

His newest album is dominated by his recent cantata A Time to Dance, in which the interrelated themes of the ages of the human lifespan, the seasons of the year and the hours of the day are fascinatingly interwoven via a series of carefully-selected texts, all accompanied by a Baroque orchestra (a choice rooted in simple pragmatism - the work was originally commissioned to share a concert with Bach's Magnificat, and was thus specified to have the same instrumentation).

I spoke to Alec during breaks in the recording of this work with Ex Cathedra. Here are some of his thoughts on his cantata.

You use the chimes of the handbells at strategic points to denote the passing of time – striking the hours of three, six and so on – and the work’s diverse texts tightly integrate the times of day, of the year and of human life. How did you manage to find texts reflecting all three parallel progressions as closely as your music does?

The two temporal cycles, Times of Day and Seasons of the Year, are favourite subjects for poets, as they offer such rich possibilities for metaphor when dealing with the human condition. There was no shortage of material; I simply had to spend a lot of time (well over a year) searching and sifting.

Occasionally I’d find something which hit both nails on the head – Marlowe’s “In summer’s heat and mid-time of the day”, for example. But the key question for any text is will it set well to music? My way of discovering this is to take the words for a walk, speaking them out loud, internalising their inherent musical qualities and discovering whether they move me, and how they make me move.

For a large work of this kind, there is the added complexity of finding how the texts speak to each other in different proximities and relationships – how does a ‘twinkle’ in summer’s heat (No. 9) compare with an autumnal ‘twinkle’ (No. 16), for example. So, assembling the text was a time-consuming process, but one in which much compositional activity must have been going on subconsciously, because when I had the words finalised, the musical setting progressed relatively quickly. Even now, I’m discovering interesting cross-currents in the texts which clearly have influenced the music, but which I was not aware of at the time. Even if the music is not to your taste, I hope you’ll agree that the text has been assembled from quite a nice selection of English poetry.

There are, as you hint in your accompanying notes, four musical quotations from Vivaldi waiting for the sharp-eared listener to pick out. Are these just a bit of fun on your part, or is there a deeper significance to them?

For me, creating music is a lengthy and arduous process; I have to find ways of keeping myself amused in the long lonely hours. This might be by setting myself a particularly knotty technical challenge – concealing an intricate canon below the surface of the music, for example, or hiding occasional musical puns within the texture. Mention of ‘the seasons’ is almost guaranteed to bring Vivaldi to mind, and I couldn’t resist incorporating a few references to his music, although I now regret mentioning it in my notes for the CD booklet. Vivaldi is a generous composer, his musical ideas ripe for further development, as Bach so often demonstrated. My Vivaldi references vary from a short snippet of melody, to a quite sizeable, much re-composed section, but they have no “deeper significance”, and you haven’t missed anything if you don’t recognise them.

Musically this is a gloriously eclectic piece, with milonga-inspired movements sitting along Philip-Glass-esque polyrhythms, all set within the mould of Baroque-derived instrumentation. What would you say are the most significant influences on your compositional style?

My “compositional style” is something I never think about. It’s like asking why do you walk the way you do, or speak the way you do? I’m just intent on where I’m going, or what I want to say. We are what we eat; and since it’s a question of taste, that applies in music too. Someone whose musical memory-banks are nourished by copious helpings of say Rachmaninov; Eisler; Dangdut; Haydn; Eccles; Rheinberger; Reggae; Isaac; Nono or Gagaku, might initially hear their echoes in a piece of music new to them (whether they are actually there or not), because listening is a creative process of making musical sense of what we hear. The process will vary from listener to listener according to their accumulated experience and tastes. And nowadays when every conceivable kind of music is instantly accessible at the click of a mouse, the possibilities are legion. But I digress. My influences?

Well, it’s clear that the years I spent in the study and practice of Javanese gamelan music have been a huge influence. What interests me is adapting the deeper structures and compositional principles of gamelan music to Western resources. Steve Reich put it quite neatly: "one can study the rhythmic structure of non-Western music and let that study lead where it will, while continuing to use the instruments, scales and any other sounds one has grown up with". One of the most formative things I grew up with was singing, so I feel very much at home composing vocal/choral music. But when I come to work in a new medium, I take time to study with a master in that form. So when I was commissioned to compose a string quartet, for example, I spent a lot of time listening to Haydn. A Time to Dance is my first attempt at a cantata. I’m keen to do more, and so I’m now spending a lot of time listening to Bach.

Performers often have to be reminded –particularly when performing Baroque works – that the style is ultimately rooted in dance music. Which of course it is! And your music – both A Time To Dance, but also the similarly light-footed Hatfield Service – clearly pays homage to this tradition. Is this something you try to involve in all the music you write?

For me, music is rooted in the body – in song and dance. When we are deeply affected by music, we say we are moved by it. For music to happen, something has to move to set the air vibrating: bow; string; lips; tube; hand; drumhead; breath; vocal cords. In the lovely imagery of the final poem in A Time to Dance, music comes into being when the air is made to dance. For me, the most inspiring composer from this point of view is Bach. His music is infused with the spirit of dance. He must have been a great dancer – just look at the pedal parts in some of his organ works! Even in the most deeply felt movements of the great Passion settings, his music sets the spirit dancing. And for me, the measure of great Bach performers is the way they make the music dance. That’s one reason why I feel so privileged to work with Ex Cathedra’s inspirational conductor, Jeffrey Skidmore. So yes, I spend quite a lot of time both singing and dancing around when I’m composing, although I make great efforts not to disturb the neighbours.

This may be a rather unfair question to ask a composer about their own work, but do you have a favourite movement from this cantata?

I completely agree with you – an unfair question. It’s like asking parents which of their children they prefer. So here’s an answer to a different question: Yes, the experience of working on A Time To Dance has really whetted my appetite for composing for ‘period’ instruments. I don’t like them because they are old; exactly the opposite: for me they are new, fresh and wonderfully subtle, sounding particularly well in balance and counterpoint with the human voice. So, yes, I’d love to do more (potential commissioners, please note!).

A Time to Dance is released on Friday 29th January on Hyperion.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC