Interview,

Gabriel Jackson on Vox Clara

The British composer Gabriel Jackson has made something of a specialism of choral music, developing a unique and instantly-recognisable style. For over a decade now he has had a close musical relationship with the choir of girls, men and boys at Truro Cathedral, and his latest disc, Vox Clara, is not only performed by the choir but also features several works written for them.

The British composer Gabriel Jackson has made something of a specialism of choral music, developing a unique and instantly-recognisable style. For over a decade now he has had a close musical relationship with the choir of girls, men and boys at Truro Cathedral, and his latest disc, Vox Clara, is not only performed by the choir but also features several works written for them.

I spoke to Gabriel earlier in the week about the pieces on the album, and the compositional thoughts behind some of them.

Three of the works on this album feature the saxophone, and you’ve also featured the cello, flute and electric guitar in other choral pieces. Where did this idea of “choir plus obbligato” first come from, for you?

It’s always come from the commissioner. Not no faceless angel was for the Royal College of Music Junior Department Chamber Choir, which is full of very fine instrumentalists – featuring a couple of them was an obvious thing to do. Ave Regina caelorum was commissioned by King’s Place, The Sixteen and the International Guitar Foundation so a guitar was always part of the brief, though the choice of an electric instrument (for its greater coloristic possibilities) was mine. In the case of Vox clara ecce intonat, Andrew Nethsingha, who commissioned the piece for his choir at St John’s, Cambridge, likes an obbligato instrument that isn’t the organ in his Advent commissions. The saxophone is my favourite wind instrument; and the soprano saxophone, especially, is so loud it can never be drowned out by the choir, which is rather useful!

You’re not the only contemporary composer to have revisited the idea of plainchant in a new guise, as you do in your neo-fauxbourdon Canticles – James MacMillan has done the same thing in some of his recent works. Do you think chant is making something of a comeback as a sacred compositional style in its own right (as distinct from merely a form of easy listening)?

To be honest, I don’t really know. I am not actually terribly interested in plainchant per se, but monodies (whether a kind of quasi-chant or something much more ornate) have always been an important compositional building-block for me.

Indeed the Canticles as a whole seem to fit very much within the current trend among choral composers to seek a simple, self-effacing style in sacred writing; would you say the understated approach taken by, say, Tavener and Pärt has influenced you in these pieces?

When I was younger John Tavener was very important to me. From his works of the early 1980s I learned how it was possible to build substantial, powerful pieces from very simple ingredients. I also admire the intense rigour of Arvo Pärt. But I’m more interested in directness and clarity than simplicity as such; of the pieces on the new disc, the Canticles are unusual in their restraint.

That Wind Blowing And That Tide is the result of a collaborative workshop with the trebles of the choir; do you think this is an approach that composers should take more often, involving the performers-to-be in the creative process?

It’s not for me to say what other composers should do, but I certainly found the process of devising the piece together with the Truro boys very rewarding. They had lots of ideas and everything we had agreed on went into the finished piece. I recently wrote a piece for a choir, Extraordinary Voices, from Newham in London, and the children not only decided what the piece would be about but they wrote all the words. I wouldn’t always want to work this way – sometimes it’s nice to do exactly what I want! – but I think it’s very important that the commissioner should have a role in the creation of the piece, however that role may be realised.

You mention in your notes that when writing for an ensemble you know personally, the individual musicians themselves are a key influence on how the work turns out, as well as the physical configuration in which they perform. Doesn’t that create something of a paradox when one of these works you’ve written for the choir at Truro comes to be performed by a different choir in a different building?

I suppose it could do, couldn’t it? But thinking about those things is really a way of informing compositional decisions. For example, the acoustic of Truro Cathedral (like many cathedrals) is quite light in the bass, so it’s a good idea not to divide the basses unless absolutely necessary. Again, the boys at Truro Cathedral are especially good at singing long, sustained line, so I make a feature of that kind of material in one or two pieces. At the same time, I am always aware that other, perhaps differently constituted choirs might sing these pieces. Just as in the hands of Pollini, say, the Appassionata Sonata becomes a slightly different piece to what it is when played by Alfred Brendel, every different performance of a piece of mine remakes the piece slightly. And that’s fine. But perhaps there is a special authority to a performance by the artists a piece was written for.

Other recent recordings by Gabriel Jackson

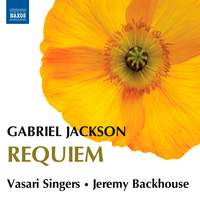

Jeremy Backhouse and the Vasari Singers perform Jackson's Requiem and other works (by Jackson, Chilcott, Pott and Tavener).

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC

The striking 'Airplane Cantata' features Rex Lawson on the pianola; also on this album is Jackson's unaccompanied, London-themed Choral Symphony.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC