Interview,

Vasily Petrenko on Tchaikovsky

Since his first appearances with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra a little over ten years ago, Russian conductor Vasily Petrenko has taken the orchestra from strength to strength, both in the studio and in the concert-hall – their Shostakovich cycle on Naxos scooped awards including a Radio 3 Building a Library first choice (for No. 8), numerous nominations at the BBC Music Magazine and Gramophone Awards (including winning the Orchestral Category of the latter in 2011), and three Disc of the Week spots in our own newsletters, whilst their recent live Beethoven symphonies cycle was praised by The Guardian for the ‘total rapport’ between Petrenko and his players.

Since his first appearances with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra a little over ten years ago, Russian conductor Vasily Petrenko has taken the orchestra from strength to strength, both in the studio and in the concert-hall – their Shostakovich cycle on Naxos scooped awards including a Radio 3 Building a Library first choice (for No. 8), numerous nominations at the BBC Music Magazine and Gramophone Awards (including winning the Orchestral Category of the latter in 2011), and three Disc of the Week spots in our own newsletters, whilst their recent live Beethoven symphonies cycle was praised by The Guardian for the ‘total rapport’ between Petrenko and his players.

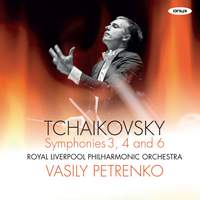

As their glorious Tchaikovsky symphonies series comes to a close (the final volume’s due out tomorrow on Onyx), I spoke to Vasily yesterday to discuss his life-long love-affair with Tchaikovsky’s music, the particular challenges presented by the symphonies on this latest recording, and the evolution of his relationship with his Liverpool orchestra over the past decade.

This new disc is the fruit of long-term immersion in Tchaikovsky for you and the Liverpool Philharmonic – what can you tell me about your very first exposure to his music?

The first encounter happened in my very early childhood, because Tchaikovsky was such a big part of repertoire in the Soviet Union: of the symphonies, I think perhaps No. 6 is strongest in my memory, because it was a signature-piece of Yevgeny Mravinsky and the Leningrad Philharmonic at that time. And I saw quite a few full ballets, because The Nutcracker, Swan Lake and Sleeping Beauty were an obligatory part of Christmas and New Year for any Soviet child! So Tchaikovsky was always there, and I also started exploring the piano music very early – you get started on Album for the Young (or even easier pieces) by the time you’re four or five years old. The symphonies I suppose I discovered much later, but for me it’s all part of one very important project because firstly of course I was born in Russia, and secondly because here in Liverpool we’ve become known for the most Russian orchestral sound outside of Russia! So for us to perform these symphonies here, and then to have so many funds for recordings, is a very special thing.

The Pathétique is arguably the most popular and best-loved of the six symphonies – why do you think it casts such a particular spell over performers and audiences?

No. 6 is a very special symphony for several reasons: because of what happened with Tchaikovsky after its premiere, and because of the mystery of the subject itself (the theme of life and death which he was exploring in all of the last three symphonies, and in the operas which were written in between). And I think it is so very personal in many circumstances, for any conductor and any orchestra. I once conducted a performance and left the stage without any applause – people were so moved and touched that they didn’t clap even when I left the podium. (And I couldn’t exactly turn around and bow immediately, because that would break the spell!) It’s very dramatic, in a particular way – it’s introverted and extroverted at the same time. And unlike any other Tchaikovsky symphony, where he explained a little bit about what the piece meant for him and what sort of moods he was trying to evoke, he didn’t do this for the Pathétique because he died so very soon afterwards. So we have to draw on our imagination: it’s like Beethoven, who explained about every symphony but 9! And who knows where he’d have gone after No. 9…?!

Conversely, No. 3 is sometimes seen as a bit of an ugly duckling – what challenges does it present, and why do you think it hasn’t enjoyed the popularity of the others?

Three is not an easy symphony: it certainly doesn’t play itself! He plays with quite large structures in all the symphonies, but in 3 you really have to know how to deal with repeated material, and also how to balance an orchestra because if you just do everything well that’s written in the score then it ends up feeling like about five minutes of music! So in those respects Three is actually quite difficult and challenging for a conductor - and also for the orchestra, it’s really not an easy or sympathetic work to play from a technical point of view.

Earlier on, you mentioned your cultivation of the ‘Russian orchestral sound’ in Liverpool, something which has cropped up in many reviews of this Tchaikovsky cycle (and indeed your work in Liverpool as a whole): how would you define that ‘authentic’ Russian quality in the first place, and how did you go about developing it with an English orchestra?

Now this is something that’s so difficult to describe briefly! I would say that the most authentic aspect of the Russian sound lies in the quality of the strings, and that’s to do with the fact that becoming a professional orchestral musician is something that’s just not taught in Russian conservatoires – you study as a soloist, whatever your instrument, so imagine that your string section contains just soloists! And this is a huge benefit, because of course most of them emerge with such great technique and skill: they’ve all studied really hard with a view to having a career as a concerto soloist, and because of that the sound is definitely richer, stronger, rounder. But the downside of that, of course, is that everyone has his or her own opinion about every single note! And to bring this all together and to make the sound meld and gel…well, sometimes in Russia that’s really, really challenging and difficult. So the combination of those two factors makes the string sound very profound, very sustained, and this is something I’ve been growing here in Liverpool – looking at attack, bow distribution, vibrato, articulation, all these technical aspects are part of what we’ve been working on together for the past ten years.

Of course it’s also to do with the quality of the brass – and I’m very glad to say that in Liverpool that quality was already really very high indeed, so for me it was just a case of encouraging them to play with a full sound, but without shrieking, or screaming, or making everything over-loud! And this is especially crucial with Tchaikovsky, who can often provoke the brass to play over-loud – so conductors have to know how to balance, how to encourage them to play beautifully. So these are all things which fit together for us, and I have to say that it pays off not just in Tchaikovsky: we have another Elgar symphony coming out [on Onyx on 24th February] quite soon, we have a Mahler cycle coming up, and just at the start of this season we did a full Beethoven cycle, which was massively popular with audiences. I think obviously a lot of the attention from the press, the ‘media angle if you like’, was very much ‘Oh there’s this Russian conductor, so let’s say that he’s very strong in Russian repertoire!’, but this orchestra is great in anything that they take on and we’re so much looking forward to doing many concerts of different repertoire!

Vasily Petrenko's new disc with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra is released on Onyx tomorrow.

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC