Interview,

Brett Dean on Hamlet

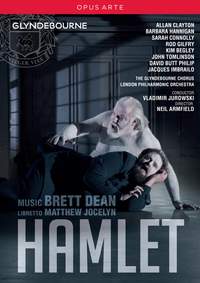

One of the most memorable musical events of 2017 for me was the world premiere of Brett Dean’s Hamlet at Glyndebourne: setting a libretto by Matthew Jocelyn (which plays dazzlingly fast-and-loose with the various versions of Shakespeare’s text) and brought vividly to life by a stellar cast including Allan Clayton as the Prince of Denmark, Sir John Tomlinson and Sarah Connolly as his parents, and Barbara Hannigan as Ophelia, it was an unforgettable night in the theatre and I'm thrilled that it’s been released on DVD and Blu-ray for posterity.

I spoke to Brett recently about the challenges involved in setting one of the most iconic plays in the English language, his working relationship with librettist and singers, the influence of other contemporary productions of Hamlet, and whether more Shakespeare might figure in his future…

One of the most memorable musical events of 2017 for me was the world premiere of Brett Dean’s Hamlet at Glyndebourne: setting a libretto by Matthew Jocelyn (which plays dazzlingly fast-and-loose with the various versions of Shakespeare’s text) and brought vividly to life by a stellar cast including Allan Clayton as the Prince of Denmark, Sir John Tomlinson and Sarah Connolly as his parents, and Barbara Hannigan as Ophelia, it was an unforgettable night in the theatre and I'm thrilled that it’s been released on DVD and Blu-ray for posterity.

I spoke to Brett recently about the challenges involved in setting one of the most iconic plays in the English language, his working relationship with librettist and singers, the influence of other contemporary productions of Hamlet, and whether more Shakespeare might figure in his future…

(Look out for my companion-interview with Allan Clayton about the project later this week…)

Tell me a little about the nature of your collaboration with Matthew Jocelyn - how much were you involved with the crafting of the libretto itself from Shakespeare's own texts?

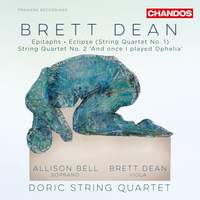

Our working process evolved over a fairly long period of time, partly through working together on a smaller-scale piece for string quartet with soprano which ended up being titled And once I played Ophelia. It was a great learning-curve to work with Matthew, and not only from the technical standpoint of thinking about how to set text (and particularly how to set Shakespeare): he was pivotal in the sense of demystifying the whole thing and making it approachable. I remember him asking me ‘What is Hamlet anyway?’: three different versions of the text were published in Shakespeare’s lifetime or shortly thereafter, so it was always something of a work in progress, and there are decisions arising from that which have to be made by anyone who tackles putting Hamlet on stage in whatever form. The way that we’d worked through that first piece together was very helpful in terms of finding a modus through those different versions - including some material from the so-called ‘Bad Quarto’, which we actually found very helpful and sometimes a bit of a circuit-breaker. It’s been a thoroughly fascinating process and a very collaborative relationship.

And how much input did the individual singers have into the compositional process?

I remember going to see Allan [Clayton] in the Barrie Kosky production of Rameau’s Castor et Pollux here in Berlin, which was incredible on so many levels – that evening something just clicked about who he was as a stage-animal. I’d met him a few times by then, of course, but that was one of the biggest roles I’d seen him in up to that point, and it was very thought-provoking in many ways.

Barbara [Hannigan] and I had also met previously, but on one of her visits to Berlin I showed her some fairly advanced sketches of where the part was sitting. She had a good look through it, and it was fascinating to see how she’d just spot things here and there and say ‘Oh, I’d set that word this way, and put that change of syllable here’ - so quite early on she demonstrated this very fine sense of detail, and I was aware that I was working with someone who really knows their stuff in terms of word-setting and what works in the voice. Another person who was incredibly helpful was John Tomlinson, for whom I’d previously written the orchestral cantata The Last Days of Socrates; well over a year before work started at Glyndebourne we had workshops on the piece, and both John and Allan’s feedback there was invaluable.

One of the most striking aspects of the scoring for me was your use of a semi-chorus in the orchestra-pit: at what point did you hit on that idea?

Oh, that came fairly early on. When I first told my trusted friend Simon Rattle that I'd been approached to do a big project at Glyndebourne, he pointed out to me that whatever I decided on doing I should bear in mind that Glyndebourne has one of the greatest choruses in the opera world. (There’s their Young Artist programme, of course, and various other projects to motivate young singers). When we settled on Hamlet and I met with Matthew, we searched for ways to people the piece, musically as well as in terms of theatre – and he suggested some wonderful and entirely convincing ways to do that as far as the stage chorus was concerned. But from the outset I also had this desire to expand the orchestral sound-world into a vocal one by having singers in the pit - not only for the purpose of expanding that orchestral palette, but also to create a link between the stage and the pit on another level.

Then around the same time I saw a production of Moses und Aron here in Berlin (again directed by Barrie Kosky), where voices in the pit are part of Schoenberg’s sound-world - and that was a revelation too, because although I was already on that path for Hamlet it was a great opportunity to see that in place in a production. Schoenberg actually took the idea further than I did in that certain voices are coupled with particular instruments: for instance, he puts a singer in-between the second and third clarinets, so that the voice almost functions as part of the clarinet section.

Did you draw inspiration from any particular recent productions or films of Hamlet?

Matthew and I went together to see the Lars Eidinger production at the Schaubühne in Berlin, which I found fascinating because it has a very taut structure – they used only six actors who assumed multiple roles (including just one female actor who played both Gertrude and Ophelia), and it also has a fantastic soundtrack. But what I found particularly inspiring was Eidinger’s darkly comic take on Hamlet himself (his performance is an absolute tour de force, and he improvises quite a lot in the course of it), which reminded me of something that Matthew had said to me when we first talked about doing Hamlet together…He emphasised how funny a lot of the play is and how important humour is; and then that was something that I could really see coming into focus with somebody like Allan, who brings such a sympathy to any role he plays. It’s partly because there’s always a twinkle in his eye, and yet there’s also something incredibly touching about how he uses his voice – and it was through the coupling of that sympathetic quality with his sense of mischief and boyish charm that I saw this particular version of Hamlet emerging.

Hamlet looks set to travel far and wide over the coming years - has the score been adapted or revised since the premiere?

It’s more or less the same: in the touring version for Glyndebourne we had to reduce some of the external instrumental groups a little because of the size of some of the theatres (the Theatre Royal in Norwich, for example, is so small that we couldn’t really have the full complement of percussion in the balcony), so there is this slightly smaller-scale version which could be utilised elsewhere in future...The only other place it’s been so far is the Adelaide Festival (where the score was performed exactly as it was at Glyndebourne); later this year before it goes elsewhere I’ll do a full update, which won’t involve any major structural changes but just incorporate the various minor details like dynamic changes and phrasing changes that happened along the way.

Are you tempted to tackle more Shakespeare in operatic form - King Lear, perhaps?

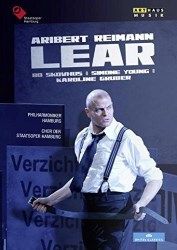

Lear would be a real contender were it not for the extraordinary Aribert Reimann version, which is such a strong piece that I don’t see any compelling reason to go there. I don’t think it would be the next thing that we do, but I’d be very interested in working with Matthew on another Shakespeare project somewhere further down the line: I got so much out of it, just delving into that world in such detail. I had a wonderful teacher in high school who took us through Lear, but it’s not as if I’d pursued Shakespeare in any great detail after that until I came to work on Hamlet. So it was a history lesson in many ways (in artistic and cultural history as much as anything else), and I can well imagine wanting to explore that path even further - but I’m not quite sure when that will happen or with which play…!

Allan Clayton, Sarah Connolly, Barbara Hannigan, Rod Gilfry, Kim Begley, John Tomlinson; London Philharmonic Orchestra, The Glyndebourne Chorus, Vladimir Jurowski, Neil Armfield (director)

Available Format: DVD Video

Allan Clayton, Sarah Connolly, Barbara Hannigan, Rod Gilfry, Kim Begley, John Tomlinson; London Philharmonic Orchestra, The Glyndebourne Chorus, Vladimir Jurowski, Neil Armfield (director)

Available Format: Blu-ray

Includes the String Quartet No. 2 ‘And once I played Ophelia’.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Bo Skovhus (König Lear), Katja Pieweck (Goneril), Hellen Kwon (Regan), Siobhan Stagg (Cordelia) & Erwin Leder (Narr); Staatsoper Hamburg, Simone Young

Available Format: DVD Video