Interview,

Scott Metcalfe on The Peterhouse Part-Books

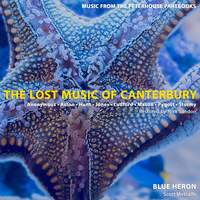

Last year saw the culmination of a fascinating musicological project exploring an often-neglected corner of the early music repertoire – for the last few years, Scott Metcalfe and his vocal ensemble Blue Heron have been busily recording a series showcasing the music preserved in the Peterhouse Partbooks, a pre-Reformation collection of original sources that escaped various waves of Protestant iconoclasm in the library of Cambridge's oldest college. The fifth and final volume was released in April 2017, and this year it's been nominated for a Gramophone Award in the Early Music category.

Last year saw the culmination of a fascinating musicological project exploring an often-neglected corner of the early music repertoire – for the last few years, Scott Metcalfe and his vocal ensemble Blue Heron have been busily recording a series showcasing the music preserved in the Peterhouse Partbooks, a pre-Reformation collection of original sources that escaped various waves of Protestant iconoclasm in the library of Cambridge's oldest college. The fifth and final volume was released in April 2017, and this year it's been nominated for a Gramophone Award in the Early Music category.

I spoke to Scott about his relationship with this music, and the various hurdles that have had to be overcome in order to bring it back to life for performance today.

Even within the field of early music, it’s fair to say that this is a relatively niche area of interest. Where did the initial idea come from to record works from this collection – did you envisage a five-CD odyssey when you set out?

The summer before Blue Heron gave its first concert in the fall of 1999, I was over at the shop in Brookline run by Friedrich von Huene and his family, browsing through music in a filing cabinet, when I came across a piece, Ave Maria dive matris Anne, by someone I had perhaps never heard of before, one Hugh Aston. It was scored for five voice parts, exactly what we were planning for, and it looked quite wonderful. The edition was beautiful, too, with a complete scholarly apparatus and extensive notes, but easy to read from and obviously made by someone with a keen sense of visual aesthetics combined with practical understanding of what performers need. 'This Nick Sandon clearly knows what he’s doing', I thought, 'and oh look, he’s reconstructed the tenor part, too!' So I took the Aston home with me, read through it, and began to realise what a find I had made - or rather, what a treasure Nick Sandon and benevolent happenstance had delivered into my hands.

Ave Maria dive matris Anne closed our debut concert, which also featured Nick’s edition and reconstruction of Taverner’s Missa Mater Christi, another Peterhouse work. By that time we’d fallen in love with Aston and we were beginning to realise just how much music there was in these partbooks: fifty pieces that don’t exist, or don’t exist complete, in any other source; works by big names like Fayrfax, Taverner, and Tallis, but also by composers we know much less well (Aston, Ludford, Pygott), some we know little about, whose music is only in Peterhouse (Jones, Mason) and a clutch of completely unknown musicians like Robert Hunt and Hugh Sturmy, not to mention 'Anonymous'! And all this music seemed to be well off the radar of performers and scholars alike; you can hardly find anything about these partbooks or their contents in studies of English music, and of course, with a part missing, the music was unperformable in our times until Nick began to publish his reconstructions.

I think the idea to record a number of discs of the Peterhouse repertoire, starting with Aston, must have come up pretty soon after that first fall, but it was quite a while before we felt ready to start - ten years, in fact! But by the time we recorded the first volume in 2009, we were planning for five.

The Eton Choirbook is perhaps the best-known of these “survivor” texts – rare collections preserving the pinnacle of the pre-Reformation English school of polyphony. Several ensembles have recorded its contents extensively. What’s different about the Peterhouse Partbooks, and why are they so special?

A generation or so separates the Eton composers from those in Peterhouse. Eton was copied around 1500, Peterhouse around 1540, and Peterhouse includes works composed over the previous couple of decades. Only one composer, Robert Fayrfax, is represented in both collections. So one obvious difference is that of style. Eton displays English sacred music at its most exuberantly Gothic, overflowing with melisma, highly ornate, fantastically complicated, sometimes in more than five parts. By the time Peterhouse was copied, that late medieval style had settled down a bit: things are rather less Gothic, one might say, and some pieces show signs of influence from Continental music, which was generally much more tightly organised in this period. But the style has settled down only by comparison with Eton: the music is still highly melismatic, the counterpoint is very free and largely not structured by imitation, and the vocal ensemble has some wonderful sonority, unique to England between the late fifteenth century and the Reformation, combining high and low adult voices (basses and tenors), with two kinds of boys’ voices, high and low (trebles and means) - not just one, the sort of middle voice that was the standard on the Continent. Those trebles were an English speciality.

One crucial difference between Eton and Peterhouse is the format in which they were copied. Eton is a choirbook, one very large volume in which all the parts appear together on the facing pages of one opening, not in score but with one part in the upper left, one below that, and so forth. The entire choir, gathered around a huge lectern, sang from this one book. So when a portion of the Eton choirbook was lost, entire pieces of music disappeared - we know of their existence only from the index - but for the rest, we have complete works.

Peterhouse, on the other hand, was a set of five partbooks, one for each voice part: treble, mean, contratenor (a part in the same range as the tenor, or slightly higher), tenor, and bass. And what happened with the Peterhouse set was that one of the five partbooks vanished, probably in the early seventeenth century, so that for music that exists in no other source (which is the majority of the 72 works copied in Peterhouse) we are missing one-fifth of the texture.

The big problem with the Peterhouse books is the missing Tenor book, which necessitated the reconstruction of an entire vocal line by contemporary scholar Nick Sandon. Can you tell us a bit about this process – and how far do you think it affects the “authenticity” of the resulting pieces?

Not only is the entire tenor book missing, a number of pages have disappeared from the treble partbook as well, so several of the pieces we recorded required Nick to recompose the treble as well: he supplied two-fifths of the texture!

I can’t provide much insight into the inner workings of Nick’s compositional process (though he’s said something about it in the notes to the new 5-CD boxed set), but I have had the privilege of looking over some of his drafts as he revises his work, and I can tell you that his sensitivity to the nuances of this very free and unpredictable style is exquisite. For every piece, applying both close study and brilliant intuition, he has been able to find a compositional manner that seems to fit perfectly into the individual, idiosyncratic style of that specific piece. There is nothing generic about his recomposition. And I do think the word “recomposition” is correct here, not “reconstruction.” He is aiming, of course, for something as close as possible to what the composer might have done, but given how many options this style allows for, it’s impossible to be certain what was there originally. It’s not a realistic goal. What Nick has accomplished, it seems to me, is to imagine himself into the mind of the composer, and the quality of his work is beyond praise.

As for “authenticity,” that’s a debate that’s come and gone in early music, thank goodness (I think it had a lot to do with marketing records of early repertoire, back in the day). What we have here is a living musician, Nick Sandon, working in collaboration with musicians who are no longer alive, making it possible to bring their creations back to life in sound, which is our job.

Do you think these pieces can now, having been rediscovered, regain a place in the repertoire of cathedral choirs in England and beyond – or is their interest today only that of historical artefacts?

No great music is simply an historical artefact, and the Peterhouse repertoire is exceptionally wonderful music, a joy to sing and a joy to listen to. I hope that it becomes much more widely known and sung by as many people as possible. It is quite difficult, of course, but no more so than the Eton music that is now much better known. And I do hope that the next survey of English vocal music to be written treats Peterhouse for what it is, the most important source of English sacred music between Eton and the Elizabethan era, rather than blithely ignoring it (as a recent book did; it’s not even mentioned!).

Can you tell us anything about your future plans with Blue Heron? Are you going to stick with this uniquely rich period of English composition, or branch out into some other area?

There’s a lot of Peterhouse repertoire we haven’t sung yet. This music will remain a staple of our programming for as long as I can imagine, and we could easily fill many discs more with it, if only we had unlimited funding. But since our first season we have also been very involved with fifteenth-century Franco-Flemish music, and at present we are about halfway through a multi-season project called Ockeghem@600, over the course of which we are performing all the music of Johannes Ockeghem (c. 1420-1497), one of the greatest composers of all time. We are embarking on a new five-CD series which will begin with two discs containing all of Ockeghem’s two dozen songs; the rest of the series will include music by his contemporaries as well. And we are also working on a recording of Cipriano de Rore’s first book of madrigals (1542), a project for which we and Prof. Jessie Ann Owens (University of California, Davis, emeritus) won the Noah Greenberg Award from the American Musicological Society. Both the first disc of Ockeghem songs and the Rore set will be released next year.

And of course we present a five-program concert series at our home base in Cambridge, Massachusetts. This season includes a production of Machaut’s Remède de Fortune - we’re also pretty active with fourteenth-century music - and for 2019-20 we are planning a large Praetorius program. While the core of our repertoire remains fifteenth- and sixteenth-century, we are always reaching backwards and forwards.

The final volume of Blue Heron's Peterhouse series was released in April 2017 on the choir's own record label.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

The full boxset, comprising the five CDs Blue Heron have released of this repertoire, will be available from September 14th.

Available Formats: 5 CDs, MP3, FLAC