Obituary,

George Hurst

At first I was in two minds about writing this newsletter as, although I personally held the conductor George Hurst (who recently passed away at the age of 86) in the highest possible regard, he wasn’t really a household name to most people. But then I decided that that actually gave me even more reason to talk about him this week. He had a profound and life-changing influence on my musical development, and countless others also, and many of the most important things I know and understand about music I learnt from George.

Born in Edinburgh, Scotland, in 1926 to Romanian and Russian parents, he was sent to Canada on the outbreak of the Second World War, and continued his musical studies there. He became professor of composition at the Peabody Institute in Baltimore at the age of 21, and whilst in America also worked and studied with Pierre Monteux.

He was persuaded by the pianist Dame Myra Hess to return to Britain in the 1950s and there basically remained for the rest of his life. Although he conducted all the major British orchestras, it was the BBC Northern Orchestra (now the BBC Philharmonic), where he was principal conductor from 1958-1968, where he really built his reputation (and that of the orchestra). Then from 1968 he was artistic adviser to the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra and its chamber offshoot the Bournemouth Sinfonietta, which he was instrumental in founding.

Equally important to George though was his teaching and nurturing of young conductors and musicians, and it is in this area that his legacy will live on for generations to come. He gave masterclasses at the Canford Summer School in Dorset for fifty years, and these combined with termly visits to the Royal Academy of Music in London and the trainee conductor schemes that were active during his years in Manchester and Bournemouth, make it hard to find a conductor emerging in the UK in last thirty years who hasn’t passed through his hands at some point. Simon Rattle, Andrew Davis and John Eliot Gardiner are just three household names and Rattle later said that it was George’s performance of Mahler's Resurrection Symphony in 1966 (when Rattle was aged just 11) that turned his head to conducting in the first place.

I attended George’s classes at Canford four years running in the late 1990s, and found the experience utterly inspiring. He was a tough teacher and his criticisms when you’re on the podium could be fierce and leave you close to tears, but his passion and total conviction to the music made it all worthwhile. The ‘traditions’ were hugely important to him, and he often made reference back to his teacher (Monteux) and the direct line back to Brahms, Berlioz and others. We worked through eight or ten set works a year, but the lessons and musical principles went far beyond those: things like what Mozart ‘meant’ by putting dots above the notes, what Beethoven meant by the term dolce, how Wagner’s concept of ‘melos’ affected other composers, and indeed where Wagner got it from in the first place.

His baton technique was mesmerising – in many ways very simple and elegant, but with so many subtle variations he could show every aspect and character of the score through what he did. This may sound an obvious thing for a conductor to do, but believe me there are plenty around today who really can’t, and only get what they want by stopping and asking for it in rehearsals. Through him I really understood how much a conductor could affect the very fabric of an orchestra’s sound, and how very different this was to merely ‘inserting’ an interpretation on top of an orchestra.

I spoke to a number of people at his memorial service in Bournemouth last weekend, all with very similar views, and I know throughout the world there are very many people indebted to George as I am. That makes me confident that the musical principles he taught will carry on into the future and be passed from generation to generation.

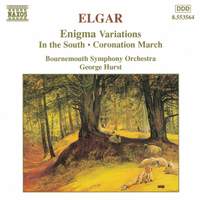

He never made that many recordings, and they’re not all currently available, but of those that are I would strongly suggest the Elgar First Symphony and the Enigma Variations (coupled with a wonderful In the South), both on Naxos. There must be loads of interesting things sitting in the BBC archives. I’ll see if I can use my connections to get some of them released over the coming years. I owe him so much, that would be the least I could do. Rest in peace George.

BBC Philharmonic Orchestra, George Hurst

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, George Hurst

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC