Interview,

Manfred Honeck on The Epic of Gilgamesh

Fifteen years in the gestation, Martinů’s Epic of Gilgamesh (first performed in Basel in 1958) is a remarkable score with an equally remarkable genesis: inspired by the discovery of ancient Babylonian tablets (dating from between 2100 and 1800 BC) by British archaeologists in the mid-nineteenth century, Martinů created his own English-language version of this sprawling story of conflict and mortality from a translation by Reginald Campbell Thompson, though the first performance of the work was actually given in German and the original was quickly superseded by a Czech translation that remains standard today.

Fifteen years in the gestation, Martinů’s Epic of Gilgamesh (first performed in Basel in 1958) is a remarkable score with an equally remarkable genesis: inspired by the discovery of ancient Babylonian tablets (dating from between 2100 and 1800 BC) by British archaeologists in the mid-nineteenth century, Martinů created his own English-language version of this sprawling story of conflict and mortality from a translation by Reginald Campbell Thompson, though the first performance of the work was actually given in German and the original was quickly superseded by a Czech translation that remains standard today.

Earlier this year the Austrian conductor Manfred Honeck presided over the first-ever commercial recording of the original English-language version of the piece, with a largely Anglophone line-up of soloists and British actor Simon Callow in the pivotal role of the narrator. I spoke to Mr Honeck recently about the extraordinary challenges which the piece presents for its massed choral and orchestral forces, the influence of other large-scale oratorios on Martinů’s approach to its composition, and why he considers Gilgamesh to be the composer’s masterpiece.

This is one of Martinů’s last major works, and is lusher and more Romantic than many of his previous compositions – do you think it represents a break in style with the neo-Classical and jazz elements he’d explored earlier in his career?

I find it so interesting that many composers who go through a lot of different stages in their life (in terms of both personal upheaval and stylistic experimentation) end up coming back full-circle. Take Arnold Schoenberg, for example: the works which he produced towards the end of his life are so very different from what he wrote in the 1910s and 1920s, and something similar happened with Martinů. He was born in Bohemia and was a violinist in the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, and then he went to Paris where he was very influenced by Impressionistic elements; he came into contact with the music of Igor Stravinsky and Les Six and so on, and learnt jazz, but throughout all of this he remained passionately in love with Czech folk music. I think he was enormously influenced by the people around him throughout his life (especially later on, during his time in America) - but he still understood the value and quality of the Czech Romantics, so for me it’s not a surprise that in this late work he goes back to his own musical language.

Your recording is unusual in that it uses the original English-language version of the text - why do you think it’s been eclipsed by the Czech translation?

Yes, in fact this recording is the first in the English translation. The original text was actually found by English archaeologists in 1849 (not far from Nineveh, where the story is set, and which as we know from The Bible was a very important city in ancient times) and Martinů worked from an English translation [by Reginald Campbell Thompson]. But I believe that he was not exactly satisfied with the English version: language was so deeply related to music for him, and I believe he found it quite difficult to connected some of his musical ideas to the English language. His musical language is always Czech, even when he’s working with foreign sources and texts. With Martinů (as with Dvořák and Smetana), I find that once you speak the Czech musical language you never leave it for your whole life – it influences and infuses every aspect of your music-making. Interestingly, the world premiere actually happened in the German language – it was only later on that there was a Czech translation, and this is actually the version which most people know today.

What are the main challenges and rewards of the score for you?

The first challenge is to uncover the many hidden meanings and connections in the motivic work, and then to start building a bridge from the first bar to the very last. It’s not like an opera, where the narrative is basically linear - you have to uncover the connections between all the segments, and that’s really the key to understanding the structure. Technically, it’s pretty demanding for the orchestra (there are a lot of fantastic solos), but even more so for the singers, who have a simply enormous work-load! The choral writing in particular is terrifically demanding, especially in terms of intonation, and they just have a huge amount to sing. And let’s not forget the speaker, who doesn’t have an especially big role but does have to convey a vast range of colours and feeling for the language.

One other challenge is that sometimes the soloists have to switch between singing and speaking (you find something similar in the ‘gesungene Sprache’ passages in Berg’s Wozzeck): it’s not always easy to achieve that, but these fantastic soloists which we have on this recording certainly manage it!

Because of the Babylonic setting, I found myself thinking of Belshazzar’s Feast rather a lot when listening to this piece – do you see any parallels with that, or indeed with other twentieth-century oratorios?

That’s definitely true: a Biblical text with Babylon as a theme, massed choral and orchestral forces (though Gilgamesh is an oratorio in three parts, and Belshazzar’s Feast is a cantata)… I’m pretty certain that Martinů was familiar with Belshazzar and whilst I think he was very anxious not to copy, there’s definitely a sense of him building on that tradition. I think he was impressed by the power and the scale of what Walton had achieved in terms of the treatment of these huge orchestral and choral forces, and I find a lot of those same elements in Gilgamesh. But I also see parallels with Franz Schmidt’s Book with Seven Seals, which was written nearly at the same time as Belshazzar’s Feast (1936/37), and which I’m also sure Martinů knew: Schmidt was someone else who really understood what you can do with a large-scale orchestral and choral canvas.

Martinů was normally an extremely speedy and efficient worker – why do you think he spent such an uncharacteristically long time (nearly fifteen years!) on this particular score?

I think it was partly down to his own life circumstances - let’s not forget that he had to escape Europe during the Second World War and went to America where he started a completely different life, so it wasn’t so easy to concentrate on such a difficult, complex subject. But I do know that he wanted to do something really special with this piece, which in fact I think is one of the greatest things he ever wrote. He was initially attracted to the Epic of Gilgamesh because he was interested in the stories (he was actually given the book by the wife of the conductor Paul Sacher, and we know that it made a very strong instant impression on him), but he knew almost as soon as he started working that he wanted to focus on the philosophical elements rather than the historical ones - it was so important to him to tell a story about life and death, to express himself and what he’d experienced as well as to explore the universal themes in the text. He’s interested in posing the big questions: why are humans here? Why do we die? Every human experiences a longing for something greater, but in the end we are human and have to die: Gilgamesh is longing for immortality, and there is no answer in the music, but there’s tremendous compassion. Martinů was completely preoccupied by all of this, and you can’t work through that kind of thing in three or four weeks – but when he finally completed it in 1958, he was so ready and so happy to have something that he felt truly proud to stand behind. It’s a masterpiece, and I think he felt that also.

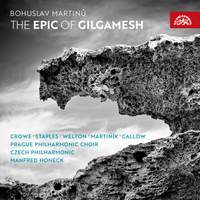

Martinů: The Epic of Gilgamesh

Lucy Crowe (soprano), Andrew Staples (tenor), Derek Welton (bass-baritone), Jan Martiník (bass), Simon Callow (narrator); Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Prague Philharmonic Choir, Manfred Honeck

The Epic of Gilgamesh was released on Supraphon on 20th October.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC