Interview,

Robin Ticciati on Duruflé and Debussy

Since taking up the position of Music Director of the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin in 2017, British conductor Robin Ticciati has been on a mission to explore French repertoire which hasn’t figured prominently in the orchestra’s history; following luminous accounts of Debussy’s La mer and Ariettes oubliées and music by Ravel and Duparc, he’s introduced the Rundfunkchor Berlin into the mix for their new recording of the Duruflé Requiem and Debussy’s Nocturnes, released on Linn tomorrow. I spoke to Robin last month about how the orchestra responded to their first encounter with the Duruflé, why he thinks the piece is often unfairly maligned, and his reasons for juxtaposing the Requiem with Debussy’s orchestral triptych from forty years earlier.

Since taking up the position of Music Director of the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin in 2017, British conductor Robin Ticciati has been on a mission to explore French repertoire which hasn’t figured prominently in the orchestra’s history; following luminous accounts of Debussy’s La mer and Ariettes oubliées and music by Ravel and Duparc, he’s introduced the Rundfunkchor Berlin into the mix for their new recording of the Duruflé Requiem and Debussy’s Nocturnes, released on Linn tomorrow. I spoke to Robin last month about how the orchestra responded to their first encounter with the Duruflé, why he thinks the piece is often unfairly maligned, and his reasons for juxtaposing the Requiem with Debussy’s orchestral triptych from forty years earlier.

This is the third recording that’s grown out of what Magdalena Kožená described as a ‘real treasure-hunt’ for French repertoire that was new to the orchestra when we spoke with her about your Ravel/Duparc recording last year: what special rewards and challenges did the Duruflé present to players and singers who were relatively unfamiliar with the piece?

It’s been a work that’s been in my heart for a long time, and at this point in this French ‘treasure-hunt’ it suddenly felt like the right thing to do to bring the Rundfunkchor Berlin on board. The orchestra had never played it before, and it’s just fantastic when a piece feels like a gift, like something new: the level of exploration and revelation in the process feels maximised. It was also interesting to look at the piece's discography: there's the odd concert-hall recording, but the majority are cathedral choir performances, and what I think’s really exciting is to treat the orchestral score as something that’s incredibly refined, powerful, perfumed and dramatic, rather than viewing it as a backing-track to great choral writing, or allowing it to be clouded in so much incense that it just becomes a mist. In a way that comes from the French Impressionist school. We’ve spoken before about this love of mine about finding Pointillist detail in French music as well as incredible washes of sound: I think it’s possible to do both, and the Duruflé was a really wonderful piece work with in that respect. And on a personal level it’s a challenge to deal with the Requiem text as something that’s contemplative and meditative, but also at times totally operatic and dramatic – I really enjoyed playing with that balance throughout the piece.

Going back to your comment about the Duruflé discography, a lot of recordings couple it with the Fauré Requiem: was that a pairing you wanted to avoid, and do you think that the piece has been eclipsed by the Fauré's popularity??

Certainly it’s not often thought of as a go-to Requiem in the same way that the Fauré is: I don’t think the Fauré’s fundamentally more accessible in any way, but it just seems to have taken that place. I’ve heard musicians that I admire greatly arguing that the Duruflé's not the most complex of pieces, or that there’s an element of kitsch to it - and with a certain part of my brain I do see how people can experience the piece in that way and therefore not be drawn to it, but I feel there’s an honesty behind it which is very moving.

Structurally, too, they’re very different pieces. Fauré takes just three pages to confront the darkness of the Dies Irae: there’s a certain emotional tension generated by having such a limited amount of time to respond to that earth-shattering moment, but if you really look into it and respond to it as Duruflé does it’s deeply moving, and something that you can really grow with. And a lot of the Duruflé is incredibly pictorial: for me, all that modality at the beginning conjures up a procession of pilgrims coming from afar. In terms of the structure of the recording, I thought a lot about how to present the Duruflé, and I loved the idea of putting it next to Debussy’s masterpiece. I remember reading that Debussy described the opening of Nuages as ‘grey upon grey’, and I wanted to put the Duruflé in that context, so that the pilgrims of the Kyrie emerge from the opening movement of the Nocturnes. And somehow Sirènes cross-references with all those unaccompanied soprano lines in Duruflé’s In Paradisum when they’re talking about St Michael leading them out of war, both in terms of story-telling and sound.

The settings of the Pie Jesu are utterly different as well. Whereas in the Fauré you have this childlike vision, Duruflé presents us with the figure of the mother – there is something so adult, so broken about that movement, and I loved having the vulnerability that Magdalena brings to it. She can be so powerful in her delivery of text and sound, yet she's also willing to let her voice speak like a nineteenth-century instrumentalist. That’s when I think her voice is released in the best possible way, and I was really pleased that rather than having a typical contralto sound here we were able to find something very multi-dimensional.

It's evident from talking with you and Magdalena that the two of you have a very special artistic rapport - when did you first work together, and how has your relationship developed?

The first time we made music together was with Les Nuits d’été in Bamberg, and what’s always stayed in my mind was the incredible way she responded to those poems – I remember sitting in while she worked with a rehearsal pianist, just listening and reacting to what she did. In terms of our working relationship there’s been real development, and French repertoire and that particular piece has felt quite central to it. Last season we performed it together again with the Chamber Orchestra of Europe, and it was so beautiful to realise not just how much I’d grown, but also how I could conduct her in a way that made her feel freer and able to create even more colours. And of course it makes a difference knowing her personally – having meals together, being with her children, just sitting and chatting…it all feeds into the music. There are instrumental soloists that you meet in the rehearsal-room and on the podium and the relationship can be incredibly intense, yet once you leave the building there’s not the sense that you would spend time with that person. It’s hard to articulate without it sounding like a cliché, but music must embrace life, and making music must embrace life, in all its complexity and messiness.

Given that so much of this French repertoire is new territory for the orchestra (and presumably for audiences too?), did you meet with any resistance when you started your 'treasure-hunt'?

Not in this case, though I have experienced that earlier in my career: the first French music I ever programmed was the Fauré Pélleas et Mélisande, and I do remember my love not quite being matched by the audience’s reaction, or even by the orchestra’s! Fauré’s an interesting case more generally: I’ve just been discussing his Pénélope here at Glyndebourne [where Ticciati was conducting Rusalka and La damnation de Faust], and I think a lot of people just don’t really get it, but in Germany things are slightly different. Certainly my orchestra are very open, and they absolutely loved playing the Duruflé - what I found very special was that they didn’t bring any preconceptions like ‘This doesn’t have the rigour of Germanic structure’ or ‘Twentieth-century music must fit a certain form’. Recording the piece was an emotional experience for us all: they were totally open to being moved by music which at times can even be filmic in the best sense. Interestingly, the Orchestre de Paris have never played the Duruflé, and I’m going to perform it with them in a year’s time: in France there is this quite complicated discourse about what’s perceived as ‘proper’ music, but I feel that if music’s presented in the right way, and if you really believe in it and are really touch with what you want to say about it then you meet with less and less resistance.

Magdalena Kožená (mezzo), Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Rundfunkchor Berlin, Robin Ticciati

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

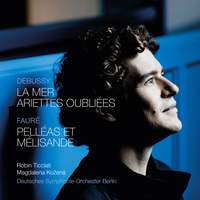

Magdalena Kožená (mezzo), Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Robin Ticciati

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Magdalena Kožená (mezzo), Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Robin Ticciati

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC