Interview,

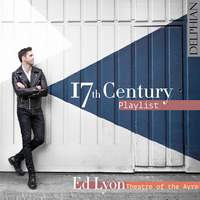

Ed Lyon on his 17th-Century Playlist

The English tenor Ed Lyon has an impressive string of oratorio and opera recordings to his name, but has bided his time before making his debut solo album; released tomorrow on Delphian, 17th Century Playlist sees him joining forces with Theatre of the Ayre (featuring lutenist and theorbist Liz Kenny, whom David interviewed earlier this summer) for a programme of mostly unfamiliar but often irresistibly catchy songs by composers including Landi, Dowland, Guédron and Cavalli. We met up in London towards the end of the summer to talk about why he thinks there’s ‘nothing quite as sexy as baroque music’, the parallels between seventeenth-century songs and pop, and how the album reflects current listening trends.

The English tenor Ed Lyon has an impressive string of oratorio and opera recordings to his name, but has bided his time before making his debut solo album; released tomorrow on Delphian, 17th Century Playlist sees him joining forces with Theatre of the Ayre (featuring lutenist and theorbist Liz Kenny, whom David interviewed earlier this summer) for a programme of mostly unfamiliar but often irresistibly catchy songs by composers including Landi, Dowland, Guédron and Cavalli. We met up in London towards the end of the summer to talk about why he thinks there’s ‘nothing quite as sexy as baroque music’, the parallels between seventeenth-century songs and pop, and how the album reflects current listening trends.

You have quite a substantial discography in oratorio, but this is your first solo album: how did it come about?

In December 2017 I was at home recovering from a spine operation and had a lot of time to reflect on the business of singing, and it occurred to me how little making singers actually get to do in their careers. That isn’t a criticism, it’s just a statement of fact - particularly if you’re not one of the people who is on the recital-circuit, which I’m not (I’ve sung one recital in my entire life!). In most opera productions there’s somebody who tells you where to stand, somebody who tells you what to feel, somebody else who tells you what to say and how to pronounce it, somebody else tells you what speed it’s going to go, and yet another person who tells you what you’re going to wear. I’ve always had quite a strong desire to make things from scratch, but that’s generally been channelled into hobbies and outside interests: I’m quite into painting and calligraphy, and do illuminated manuscripts of my own as an outlet for that urge to create. So there I was sitting at home in Cheltenham and I thought: ‘What is it that I want to make?’. And that took me back to my abiding love of baroque music, which is still my go-to listen; I’ve always had quite a varied repertoire, but I just hit forty which is a bit of a turning-point vocally, so I thought it was a good opportunity to explore some of the earlier stuff that I’d always wanted to do but never got the chance; I’ve loved the Landi songs which are on the album for ten years.

I figured that almost everything on the album would be new to almost everybody, except the Dowland and perhaps Lambert’s Vos mépris chaque jour. The music really does rely on me and this band to bring it to life, and it’s so exciting to think that a lot of people will be hearing these songs for the first time, sung and performed by us. It’s very different from doing a mainstream album of songs or arias and being compared to Bostridge or Langridge, or even legends like Caruso or Pavarotti.

Had you worked with this particular band before?

The continuo team for the album is pretty much the same line-up that we had for L’Ormindo at the Globe in 2015, which was an incredibly rewarding experience for me: I grew up wanting to be an actor before I got into music, and in L’Ormindo I found the perfect synthesis of those things. It was one of the first times that I felt liberated as an actor, because there was no conductor and no monitors: essentially, the musicians just had to listen and to know the score really well, and they responded absolutely brilliantly.

A lot of the songs on the album seem to have a great deal in common with contemporary pop ballads, despite being written several centuries ago...

It was never about creating crossover, because I don’t believe in crossover: it was more about saying ‘You don’t need something to be crossover for it to have crossover appeal’. I think these songs are so joyful and easy to connect with: they’re genuinely catchy, memorable and easy to listen to, even if you’ve never heard them before. The average length is about three-and-a-half minutes, and it struck me how much that ties into the modern songs we all listen to and the expectations we bring to them – we expect things to be a certain length, to have verses, to include a catchy refrain, that kind of thing, and so many of these airs du cour fit the bill so perfectly even though they're unfamiliar to most people.

One of the things which struck me when I first listened to the ‘Playlist’ was the surprising modernity of not only the individual songs but also the whole sweep of the album…

A lot of those songs are literally on a playlist that I have on my iPhone, and it occurred to me that that’s how a lot of people like to listen to things today; we singers are conditioned to think about recital-work, to come up with really ingenious themes and ways of organising programmes, but I don’t believe that most people sit down to listen to a whole album any more. I hesitate to think of it as ‘background music’, but people no longer listen with their full attention all the time and I don’t think that’s necessarily a problem. What I love about this album is that you can experience it in whatever way you choose: you can listen carefully with the texts in front of you, or you can dip in and out of it as the mood takes you.

You’ve chosen to style the album as a ‘playlist’ - would it work on shuffle?

Yes, I think it would, because there’s nothing prepped and classical about it at all. But at the same time it’s not not-structured – there are all sort of ideas running through the programme, as I realised once I started to think about potential titles. I didn’t want to call it 17th-Century Love-Songs, which seemed a bit generic, but at one point I did think about calling it Songs for Celia, as her name seems to crop up all the time in these songs! It’s interesting that you ask, because the order that’s on the album isn’t actually the one I initially chose. I sent Paul Baxter [the managing director at Delphian] what was essentially a recital-order, so it was quite beautifully balanced: I’d organised it so that there was a real sequence of keys and no jarring changes of tonality, and it had a nice journey that ended on a high note, so it ticked all the recital boxes. Paul shuffled it round quite a lot and I’m so glad he did, because there are now moments where it does change gear, but it’s kind of a refresh for the listener - and it also ends on the Canta la cicaletta, which is our theorbo-player Liz Kenny’s favourite! Having that as the final track will hopefully invite the listener to leave the album running so that it starts again from the beginning; I’d originally envisaged a big finish (I went with Landi's Damigella tutta bella as the closing track), but that doesn’t work so well as a circular programme.

Is any of the music actually improvised?

Yes, and one of the things that I love about the album is that it has a slightly folky aspect to it: very little is written down and preserved in aspic. Apart from the two ritornelli that were written out (Damigella and the excerpt from Cavalli's Eliogabalo), all of the violin stuff was improvised, and of course everything that the continuo team do was also essentially improvised, because that’s just how they work. One of the reasons I wanted to start with the aria from Eliogabalo was because that’s the one that’s the most set down, and everything kind of disintegrates from there, up to a point; I love people like Christina Pluhar, but I didn’t want to get into that space where we have a clarinet jazzing away in a baroque aria!

That said, we found it quite hard to avoid being just a bit Celine Dion here and there, and for one of the tracks (Passacaglia delle vita) I asked the continuo team if we could really channel Buena Vista Social Club! I’m quite evangelistic about the Landi songs, and my favourite track on the album is Je voudrais bien Chloris: the whole scenario there is so modern (it’s essentially about a man getting up and leaving a woman after they've just had sex!), and the musical language really chimes in with that too. If you listen to French pop songs very carefully, you can hear French baroque ornaments in there even today: they fit so well with the French language, and that’s why you get whispers of Celine Dion in this music that pre-dates her by 400 years!

The album has a certain timeless appeal, but how concerned were you with historically-informed performance-practice when you were putting it together?

Snobbery is still a huge issue in early music, so I enlisted Liz Kenny to act as the Taste Police for the recording: if something was bad taste but I liked it, then we kept it; if it was objectively wrong, then Liz would veto it. It was just great to have somebody there with the authority to say ‘Sorry, you can’t start a trill from the leading-note in English music’, but what I love about Liz is that she’s never dogmatic about things. I also picked violinists who were not too hessian about vibrato, because there are a lot of fabulous string-players out there who will refer you back to some treatise that was written in the seventeenth century and refuse to use it at all. But if something sounds better with vibrato than it does without, I honestly don’t believe that musicians at the time would have said ‘Sorry, we can’t do that because it’s 1610!’.

Given all the unexpected modernity of a lot of the music, would you consider performing the programme in unconventional venues such as clubs and pubs?

I’m desperate to do that, and I’m chasing various opportunities to make it happen: the only real caveat is that the music needs venues with a decent acoustic that has a bit of bloom, because otherwise these early instruments can lack warmth. There’s this misconception that early music isn’t accessible, but I think this stuff is so much more accessible than even a Mozart symphony: after all, a lot of these tracks are three-and-a-half minute songs with verses and a refrain and somebody strumming a guitar!

Ed Lyon (tenor), Theatre of the Ayre

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC