Interview,

Two new concertos by Gabriel Prokofiev

Some instruments are more frequently seen as concerto soloists than others; wind instruments in particular have always seemed to lack the breadth of concerto repertoire that violinists and pianists enjoy. The first concerto on Gabriel Prokofiev's recently-released album helps to redress this, adding another concerto to the repertoire for the saxophone - written for and recorded by Branford Marsalis, and incorporating his specific desire for melodious lines, potentially setting the writing apart from many other contemporary works.

Some instruments are more frequently seen as concerto soloists than others; wind instruments in particular have always seemed to lack the breadth of concerto repertoire that violinists and pianists enjoy. The first concerto on Gabriel Prokofiev's recently-released album helps to redress this, adding another concerto to the repertoire for the saxophone - written for and recorded by Branford Marsalis, and incorporating his specific desire for melodious lines, potentially setting the writing apart from many other contemporary works.

The second, though, caused some raised eyebrows in the Presto office when we came across it - there have been a fair few percussion concerti, but this work focuses on the bass drum, all by itself. Surely not the most promising instrument to work with in a soloistic capacity? Well, Gabriel definitely begs to differ and indeed has found plenty of different ways to exploit the bass drum as a solo instrument... I spoke to him about both of these striking works, to unpack the dizzying variety of influences that come together in his compositional style.

Both these concerti were written for specific musicians to premiere (Branford Marsalis and Joby Burgess respectively). How close was the cooperation during the compositional process – were you left pretty much to your own devices, or was it more of a partnership as the works took shape?

It really depends on each project. I really like to work with soloists; I’m all for composing for the real world and for real situations, and therefore for real people. With Joby, I knew him well already because I’d previously done this piece Import/Export for him, which had been a real joy; so I knew technically how great, and virtuosic, and brilliant, he is – and how also, whatever I throw at him, he’ll find a way of playing it. The way the process started was that I went to his studio and we spent a day trying out every possible sound we could with the bass drum. Then, in fact, I just went off by myself and wrote the piece, and I came to him with a draft with the overall structure in place, which he then went through and fed back on, tweaking bits here and there.

It was different with Branford, in some ways; he said to me “I’m not a composer, you just do your thing; you’re the composer!” He felt it was very important to have melody, that was his big thing – which was very interesting, because so often in contemporary music melody’s not really even spoken about, which is rather weird. Branford specifically wanted it, and that was a nice piece of input coming from him. He also told me to “challenge” him, which I think maybe he regretted later!

You mention being keen to avoid the oft-trodden ground of the “jazz concerto” stereotype – how hard was this in practice, given how inextricably bound up the saxophone’s sonority is with the jazz soundworld?

It was an interesting challenge. I realised that there were inevitably going to be connections with jazz, but what I was keen to avoid was that kind of mock-jazz pastiche style of thing; I thought that would be too obvious a path to take. I thought about the instrument in terms of its sound, as abstractly as possible – thinking of it as a woodwind instrument, half-clarinet, half-trumpet and with elements of the bassoon, and I tried to see it more as part of the orchestral family of instruments rather than as an outsider.

That being said, the history of the saxophone, as this jazz instrument and this innovative instrument of the twentieth century, is an interesting and an inspiring one. Thinking about what kind of personality the saxophone has; when I thought about the great soloists – Coltrane, Parker and so on – many of them are quite tragic figures, quite lonely, a real strong sense of individualism and rebellion. So I wanted to embody that aspect of its jazz heritage, but not to fall into using jazz idioms or scales or classic jazz compositional or improvisational techniques.

Many non-classical influences are on display here – not just jazz but hip-hop, disco and punk, all drawing on your own background in non-classical dance music. How did the soloists and orchestra respond to these – styles they might be accustomed to hearing, but perhaps not to performing?

I generally find orchestras are very pleased to hear rhythmic approaches and sounds that they don’t normally hear in the orchestra; they feel quite excited by it, the way it connects a bit more than usual with contemporary life rather than being this detached kind of high art. So I find they tend to enjoy and get into it. Branford was very impressed with the Ural Philharmonic: they’re so on the beat they’re almost ahead of it, whereas he was used to American orchestras playing a bit behind the beat. And I really liked that kind of tight, precise, snappy energy; it works well with my approach. The Ural Philharmonic particularly enjoyed the bass drum concerto – I’m not sure why, but I think they liked the energy of it.

You present the final movement of the saxophone concerto as a struggle between the soloist’s individuality and the remorseless rhythms of what you describe as an “uncertain and increasingly mechanical future”. In terms of the music, who would you say wins out in the end?

It becomes kind of celebratory at the end; it certainly starts off with the saxophone gasping for air and battling, but as it progresses I get the feeling that the soloist starts to lock into the system and ride it in some way. There are moments where the orchestra overwhelm it a second time, two-thirds of the way through, but in the end I think the saxophone reaches a positive connection with this mechanised future. The piece ends with a bit of a smile, with these slowed-down rising chords in quintuple meter, and the saxophone in unison with the orchestra.

The bass drum concerto makes use of widely extended techniques. Were you aware of these when you began composing the work, or are they the results of your own exploration and experimentation in the course of writing it?

When Joby and I first spoke, we talked and brainstormed the possibilities. I can remember quite clearly that we both agreed that we were quite fed up with the kind of percussion concertos where the percussionist has a whole array of different instruments: you might have a marimba, vibes, tubular bells, tom-tom, and they’re running round playing them all. I really wanted it to feel more like a conventional concerto, so I jokingly said “well, why don’t we write one for a big bass drum?” And when we started to think about it, we realised that actually it could really work, and we started discussing different sounds – you could hit the wood, the rim, the metal, you can rub the skin of the drum…

So we had quite a good idea even beforehand – but then when we started trying them out on the drum itself, that got our thoughts going even further, and we found even more things out in terms of new ways you could interact with the instrument. For instance, with a metal beater, rattling it between two metal lugs to get a really fast, metallic trill effect; or with the dampening, if you put far too many towels on the front (rather than the single one you’d use in ordinary bass drum dampening), you get this tight, almost tom-tom-like sound. It’s such a rich instrument.

Despite your passionate advocacy for the instrument in this work, the idea of a concerto for bass drum is surely still a tough sell for anyone putting together a concert season. Do you anticipate this work breaking into the mainstream repertoire?

It’s interesting that you say that, actually. It’s been very much led by the percussionists; what happens is that most orchestras will offer their principals or long-serving musicians the occasional chance to do a concerto, so percussionists are always looking for something different and that’s what’s happened here.

The big one for me was the Buenos Aires Philharmonic – their principal percussionist had been with the orchestra for some key number of years and was offered a concerto, and he chose the bass drum concerto and contacted me. Since then it’s been done in Portugal, in France, and several times in America – so actually I think it’s the percussionists who get excited about it, and if people do get to see some video footage and see how dramatic it is then they’re more willing to take a risk on it. In some ways the drama makes it quite accessible and appealing – the visual aspect as much as the music itself.

Are there any other instruments that you feel could benefit from the same treatment as you’ve given the bass drum here – instruments generally discarded as soloists but perhaps holding hidden potential?

There are things in my mind; in the wake of the bass drum concerto, the double-bass players were coming up to me and asking about a concerto for that instrument. That’s not so rare; concertos for double bass exist already, of course. I was thinking of doing a concerto for the entire double bass section, with say five double basses out at the front: they are quite quiet instruments and often have to tune the instrument up a tone or two to project over the orchestra. I have a feeling I wouldn’t be the first to do this – in fact I think someone else is working on something similar.

But as for more unusual instruments, I’ve considered following the bass drum concerto with another for cymbals, and turn it into a series. I’d probably use a selection of different cymbals, though with a certain large cymbal we might be able to get a whole range of sounds from it using extended techniques. Or you could extend it to include crotales, which are tuned – that might be another option on the percussion side. I’m also a fan of electronic music; so I’m interested in possibly a concerto for synthesiser, maybe a classic model like the Mini Moog or something, or perhaps the theremin...I’ve worked with a theremin player previously and it’s a fantastic instrument. I actually curated a concerto for drum machine – I might just write a movement to contribute to the work (it’s currently a concerto by five different composers, each having written one movement). I’ve previously written two concertos for turntables, and an alternative to that could be someone on an MPC sampler, so you’d have a sample pad to draw on, but I don’t know if that would be as satisfying as the turntables, which worked very well.

I’m about to start on a viola concerto, but of course that’s much less unusual. It’s difficult in a way, because the viola is such a quiet instrument. The one I’m writing for is for Maxim Rysanov, who is a conductor as well, so he’s going to stop to conduct in the big tutti sections and when he’s playing I’ll drop the orchestra down to just a few sections – so that’ll be a nice way of keeping it dramatic without the viola getting drowned.

There’s also Lauri Poora, a composer from Finland who’s done a bass guitar concerto, which I think is quite a good idea; I was talking to Kalamazoo Symphony recently, which is the town where the Gibson guitar was invented, and I was thinking about a concerto specifically for a classic Gibson electric guitar, and experimenting with all the different sounds you can get from that instrument; there must already be concertos for the electric guitar but maybe there’s a niche for me too!

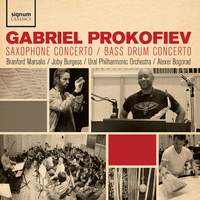

Branford Marsalis (saxophone), Joby Burgess (timpani), Ural Philharmonic Orchestra, Alexey Bogorad

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC