Interview,

Xavier Sabata on Winterreise

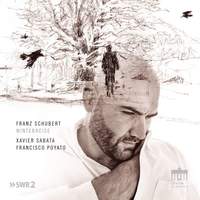

With an impressive discography of baroque recital albums and complete opera recordings under his belt, the Catalan countertenor Xavier Sabata is perhaps more commonly associated with Handel’s heroes and villains than with German song repertoire, but over the past three years or so recital work (and in particular Schubert’s Winterreise) has figured prominently in his schedule, and in November his recording of the cycle with Francisco Poyato on Berlin Classics was greeted with considerable acclaim in the German press. I spoke to him shortly before Christmas about his extensive background in lieder, overcoming resistance to countertenors performing this music, and why he thinks that Winterreise ‘could happen in twenty minutes in an armchair’…

With an impressive discography of baroque recital albums and complete opera recordings under his belt, the Catalan countertenor Xavier Sabata is perhaps more commonly associated with Handel’s heroes and villains than with German song repertoire, but over the past three years or so recital work (and in particular Schubert’s Winterreise) has figured prominently in his schedule, and in November his recording of the cycle with Francisco Poyato on Berlin Classics was greeted with considerable acclaim in the German press. I spoke to him shortly before Christmas about his extensive background in lieder, overcoming resistance to countertenors performing this music, and why he thinks that Winterreise ‘could happen in twenty minutes in an armchair’…

When and how did your love-affair with singing Schubert begin?

I’m absolutely fascinated by lieder, and that’s why I did a Masters in it: of course as a countertenor a lot of your focus is on baroque music, but having previously trained as an actor I love working with text and I really wanted to explore and understand the song repertoire from the source. When I was at the Escola Superior de Música in Barcelona I was amazed at how many people would say to me: ‘First the words and then the music’, but no-one was really teaching me how to do that in terms of colouring the text and understanding the energy of a poem, or building a psychological structure for a character.

My teacher in Barcelona sent me to Karlsruhe to work on lieder with Hartmut Höll and Mitsuko Uchida, initially on an Erasmus, but I loved it so much that I stayed on and completed a Masters degree. At the beginning I just thought it would be a good learning experience rather than something that I would ever think of doing professionally, because I was very much aware that I was a countertenor; I was doing Le Jardin des Voix at around the same time, and when you have the opportunity to work with someone like William Christie you’re not going to pass that up. But this Winterreise came at a moment in my career where I felt mature enough that I honestly don’t care about what people might say!

So you think there’s still resistance to the idea of countertenors singing Lieder?

Oh yes, there’s a lot of resistance, but the only way to counter that is just to do it anyway! I’m not going to apologise for singing this music, and I’m not going to ask for permission: I’m going to take every opportunity to do what I’m passionate about. I spent years studying lieder specifically and Winterreise is one of the things I’ve prepared in my life the longest, so I know what I’m doing – and the funny thing is that I often feel that other singers who don’t really have a proper grounding in how to approach this repertoire can very easily find opportunities to do song recitals simply because they’re tenors or sopranos and apparently that’s what they are ‘supposed’ to do. Countertenors are always being told that they aren’t ‘allowed’ to sing this or that - but now we have singers like Franco [Fagioli] with the technique and the range to sing Mozart and the big Rossini heroes, and if a singer is also dramatically credible in those roles then why not? I just want to see a well-sung Cherubino or Arsace, and I don’t care if it’s a man or a woman.

Some of the nicest feedback I received after a performance of Winterreise came from an audience-member who said: ‘After a minute-and-a-half I forgot you were a countertenor - I was just listening to what you were telling me’, and really that was my only aim with this project. The quotation on the back cover of the album sums up my perspective, I think: ‘Who can deny the universality of this music? These days, why should anyone want to limit it to a specific voice type, gender or age?’. If Schubert had known countertenors or castratos I’m convinced he would have written for them and that they would have been very good friends!

Going back to that idea of focusing on text, where did you start when it came to preparing the cycle?

I wanted to make sure that I didn’t lose the sense of where the music originally comes from: I find that certain approaches to the lied can be very manneristic in terms of overdoing the colouring of each word, and that can be extraordinary, but it comes at a price. Schubert was writing these songs for his friends to sing in his salon - maybe they weren’t even professional singers - so for me it was all about combining two ideals: understanding the fresh energy behind this music which sometimes goes against the almost sacral atmosphere that one wants to create in a Liederabend, and at the same time being flexible enough to bring out all the tiny details of the piece.

When I started settling into the idea of performing Winterreise and going through the poems (which is where I begin with any project), I got to thinking about what sort of mindset could be behind all this music. Who has the need to tell this story? What’s the unifying thread that runs through these 24 poems? And all of a sudden it came to me: Winterreise is essentially about the restlessness of the mind. It doesn’t need to be a linear narrative: it can be seen as a kind of spiral or a circular story where the character meditates on his suffering, rests for a while, then takes up the same theme again. For the most part he’s not even talking about her (she’s mentioned in just three or four poems); he’s talking about his open wound. One of the reasons that Winterreise is so relatable is that it’s essentially a cycle about suffering, by which I mean being closed off from the possibility of loving: everyone suffers in the world, regardless of wealth or privilege, and that’s why it’s so easy for all kinds of people to connect with the piece. The other day in Seville the audience was mainly made up of elderly Spanish ladies, and they couldn’t read the texts and translations because it was so dark, but I knew that they understood everything.

So you don’t have any literal landscape or time-scale in mind when you perform the cycle?

No, because I really approach it as a trip into the darkness of the mind: of course the character talks a lot about the snow and the cold, but I escaped very soon from this kind of literal narrative and began to feel that Winterreise could happen in twenty minutes in an armchair in a restless state of mind. I’m very curious about how the mind works and have worked with various meditation techniques for many years, so it’s extremely interesting to see how all these poems could be the sort of inner dialogue that someone has with himself while he’s cooking or getting on with mundane tasks. But the funny thing is that when I perform the piece, time seems to fly: I’ll get to the end of a performance and suddenly register that I’ve been singing for an hour and ten minutes!

Given your own background in theatre, what are your thoughts on actually staging the piece?

We recently did a very simple but beautiful staging by an extremely talented young Spanish director, Rafael Villalobos, at a festival in Seville. It was a very empty stage, almost like a Samuel Beckett piece, with lots of repeated images in the projections to reinforce the idea that this character can never escape from his own mind. Having the opportunity to dig into this kind of artistic material with just one or two other people is what I love the most about my career: I also love doing baroque opera, of course, but when you’re not dependent on complex scenography, a big production-team and a huge budget, the experience is akin to creating a little piece of jewellery or fine embroidery, and to me that’s extraordinary.

Are you also tempted to perform and record Die schöne Müllerin?

Everybody asks me that, but it’s really a question of age: I’m very young in my mind and heart, but I’m actually 43 now and I would rather let it be done by a younger singer. One idea that appeals to me is to do it when you’re very old so that it’s a throwback in time, from another perspective. But for now I feel closer to later works like Dichterliebe and Schwanengesang, and I’d love to do the big Schubert ballads: Der Zwerg, Erlkönig, even Die junge Nonne.

Would you ever consider recording any of Mahler's song-cycles?

That’s the next thing. I actually sang Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen at school with piano, and I would love to do the Rückert-Lieder and Kindertotenlieder. I quite often sing Strauss’s Morgen!, transposed and with a baroque orchestra, as an encore. But Strauss is very extreme in terms of range, so I don’t think everything works in transposition - sometimes you miss a certain tension that sopranos get when they sing that repertoire, but that doesn’t happen in Schubert for me, and I hope the same will be true for Mahler because I feel very close to his music.

And I can’t name names just yet, but if everything goes according to plan there is also a commission in the works for me, which will be a sort of contemporary Winterreise, setting texts by a living poet: a large-scale cycle of twenty songs with piano, telling a very vivid, real story, which is a terrifically exciting prospect.

Xavier Sabata (countertenor), Francisco Poyato (piano)

Available Format: CD