Interview,

Paul Lewis on Beethoven

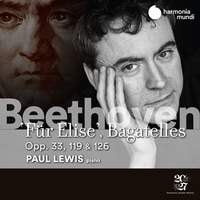

The British pianist Paul Lewis’s survey of the Beethoven piano sonatas (recorded between 2005 and 2008 on Harmonia Mundi) is widely regarded as one of the finest cycles in recent memory, with Record Review describing it as ‘a must for anybody who admires pianism at its most perceptive’, and today sees the release of his recording of the Bagatelles – works which he sees as traversing a similar path to the sonatas, ‘just in miniature form’.

The British pianist Paul Lewis’s survey of the Beethoven piano sonatas (recorded between 2005 and 2008 on Harmonia Mundi) is widely regarded as one of the finest cycles in recent memory, with Record Review describing it as ‘a must for anybody who admires pianism at its most perceptive’, and today sees the release of his recording of the Bagatelles – works which he sees as traversing a similar path to the sonatas, ‘just in miniature form’.

We spoke shortly after his live-streamed recital from an empty Wigmore Hall last month (which included the ‘Moonlight’ Sonata and one of the Op. 126 Bagatelles) about the repertoire he’s been exploring in lockdown, Beethoven’s often ‘uncompromisingly uncomfortable’ writing for the piano, and why he views the Bagatelles as a bridge of sorts between Haydn and Brahms…

Has Beethoven featured much in your music-making in lockdown?

I’ve mainly been exploring new repertoire: I started off looking at things like the Ravel Piano Concerto and a few Mozart concertos that I hadn’t played before, and also Debussy’s Suite Bergamasque and Children’s Corner. It’s been great to have the time to discover these pieces, but I’m not as obsessive as I was at the start of lockdown when I was determined not to waste a minute - now I’m finding a bit more balance between working and just enjoying being at home.

Apart from occasional little things like the odd Bagatelle here and there I’m not keen on live-streaming concerts from home, because I just don’t feel like that’s a substitute for anything: you have to ask yourself what purpose it serves. I can see that some people look on it as connecting with an audience in whatever way they can, but it’s so far removed from the experience of doing a concert that it’s not for me.

How was the experience of doing a live-streamed lockdown concert from Wigmore Hall? Did it feel closer to a live performance or a recording-session, or was it a different atmosphere from either?

Very different: I’d say it felt much more like doing a concert than a recording-session. I was very unsure how it was going to be, and when I watched Stephen Hough’s first concert in the series I thought it looked absolutely terrifying: I couldn’t imagine how it would feel to play to a microphone in an empty hall knowing that it’s being streamed to any part of the world and that the audience is out there somewhere! But when it came to actually doing it, I was pleasantly surprised at how aware of an audience I was: I was expecting it to feel a bit like a nervous rehearsal, but there was a very strong sense of being listened to even though the audience wasn’t physically present in the hall. There’s no denying the fact that a physical audience is such an essential part of a performance, because being in the presence of a group of people who are all listening intently generates such energy; you can't help but miss that, but it didn’t not feel like a performance!

You're used to playing at Wigmore when the venue's at capacity - did it take a while to adjust to the different acoustic in the empty hall?

It essentially just feels like it does in an afternoon rehearsal before a concert, and I guess that does affect the way you play: there’s more sound, it’s more resonant, and things don't feel quite as tight as they do when the hall is full. It’s inevitable that you’re affected by what you’re hearing as you play, but you have to remember that ultimately you’re playing for the microphones, not to the back of the hall: it felt like an empty hall acoustically, but you just try not to worry about that too much because it’s not what your audience are hearing.

As a veteran of the complete piano sonatas, do you see many references to the material there in the Bagatelles?

For sure, especially in the late sets and most of all in the Six Bagatelles Op. 126, which have this slightly bizarre frame: there are six bars at the beginning and the same six bars at the end, which are a sort of outburst of E flat. In between you have this incredibly intimate, reflective and introspective music, which seems to make quite a few references to other parts of his piano music - particularly Op. 111, and Op. 110 as well. Op. 126 is really Beethoven’s final statement: he did write the odd incredibly short piece after that (there’s a bagatelle from 1825 which lasts just two lines!), but Op. 126 is really his last proper piano work, and it’s kind of a summing-up of everything that’s gone before. It’s easy to think of Op. 111 as being the last work in terms of his piano music, but of course it’s really not – he develops the story much further, and Op. 126 distils it in the sense that you feel that his language has become even more extreme and more individual by that point. All of his creativity and experimentalism is right there in these pieces, but in a very distilled form: it’s extraordinary music.

And in the earlier sets we get the occasional glimpse of what's to come in the later sonatas: that foreshadowing of the Waldstein in the final Bagatelle of Op. 33, for instance…

Indeed. That’s a remarkable little piece, because he just builds it out of nothing: there are those repeated 5/1 chords and a fragment of a melody and that’s it! To construct something so entertaining and engaging and funny out of virtually no material is just astounding, but it’s also very typical of Beethoven.

Do you feel that the Bagatelles are still slightly underestimated or neglected?

I think they just aren't thought about enough, perhaps because we miss the sheer range of invention that’s present in the piano sonatas. But of course he composed them throughout his life, and in the way that the piano sonatas are a survey from the beginning to almost the end of his life, the Bagatelles are also that - just in miniature form. So yes, I do feel they’re overlooked, as in fact are some of the sonatas. Most of the sonatas which get played regularly have titles, but how often do you see Op. 54 or Op. 22 on a concert programme? They’re incredible, unique pieces, but they hardly ever crop up in recitals, and the same’s true of the Bagatelles, I think.

How do you like to programme the Bagatelles in recital – do you feel they work best as a complete cycle, or juxtaposed with other composers?

I hadn’t really thought of playing all three sets in one go, but there’s no reason why you shouldn’t! I’ve performed each set individually over the last few years as part of the Haydn-Beethoven-Brahms series that I’ve been doing: I wanted something that glued Haydn and Brahms together, and the Bagatelles seemed to fit the bill perfectly because they look in both directions. A lot of the early ones are quite Haydnesque in character: funny, mischievous and full of surprises. And I feel that in language and expression some of the later ones do point towards Brahms – they don’t particularly sound like Brahms as such, but they anticipate that deeply serious way of expressing something.

In terms of technical challenges, is there anything in the Bagatelles that's on a par with something like the Hammerklavier?

Nothing is on a par with the Hammerklavier: it’s the most stressful piece of piano music I know! But the Bagatelles are often deceptively difficult to play, and the early ones in particular are quite tricky. In the second piece of Op. 119, for instance, you have to cross your left hand over your right all the time and there’s something very counterintuitive about that – as indeed there often is about the way that Beethoven writes for the piano in general. Despite the fact that he was a great pianist, he didn’t write conveniently for the instrument in the way that Liszt or Chopin may have done: there’s something uncompromisingly uncomfortable about his piano writing, and that’s always there, so that even things that look fairly simple on the page can be quite difficult to execute. The sixth Bagatelle of Op. 119, which is the first one that’s classed as a ‘later’ bagatelle, is especially counterintuitive and somehow lies very awkwardly under the fingers.

In 2010 you became the first pianist to perform a complete cycle of the Beethoven concertos in a single Proms season: does that still stand out as a milestone for you?

It’s hard to believe that that’s already ten years ago! It was an amazing experience, and it felt like a huge responsibility to be the first person to do that – it’s extraordinary that no-one had played a complete cycle at the Proms until 2010. But once it was up and running and I got on stage a lot of that stress fell away, as it always does at the Proms: they stand out in your diary as big dates, but once you get out there that irresistible festive atmosphere takes over. When you look out at the hall from the stage, the energy that comes from the arena is unbelievable, and any worries that you might have had really do just fade away.

With the complete sonatas and concertos under your belt, do you have plans to record more Beethoven? I wondered if something like the Eroica Variations might figure in your future…

Apart from the Diabellis I haven’t recorded any of the other sets of variations, and I’ve actually never even played the Eroica Variations. That’s one glaring omission in my Beethoven repertoire, and maybe I should use what’s left of this time to plug the gap: the Eroicas are very difficult, and require a lot of knuckling down! And there are other wonderful sets like the tongue-in-cheek Rule, Britannia! variations, so there's the potential for a great CD there...why not?

Paul Lewis (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Paul Lewis (piano), BBC Symphony Orchestra, Jiri Belohlávek

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Paul Lewis Beethoven Piano Sonatas Series

Paul Lewis Beethoven Piano Sonatas Series

'Lewis's cycle of the 32 Beethoven piano sonatas is of such a high order that it promises to make the whole series a must for anybody who admires pianism at its most perceptive' (Record Review)