Interview,

Joseph Fort on Holst's Cloud Messenger

Gustav Holst's 'Indian period' saw him take a deep interest in the mythology, cosmology and music of South Asia, with the chamber opera Savitri perhaps the best-known large-scale result. Written only a few years after Savitri was The Cloud Messenger, a musical response to the epic poem Meghadūta by the Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa, thought to have lived in the fourth or fifth century AD. Holst takes this story, which sees a yaksha nature-spirit who has been exiled from his mountain home ask a passing cloud to take a message of love to his distant wife, as the starting-point for a luxurious and evocative musical work.

Gustav Holst's 'Indian period' saw him take a deep interest in the mythology, cosmology and music of South Asia, with the chamber opera Savitri perhaps the best-known large-scale result. Written only a few years after Savitri was The Cloud Messenger, a musical response to the epic poem Meghadūta by the Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa, thought to have lived in the fourth or fifth century AD. Holst takes this story, which sees a yaksha nature-spirit who has been exiled from his mountain home ask a passing cloud to take a message of love to his distant wife, as the starting-point for a luxurious and evocative musical work.

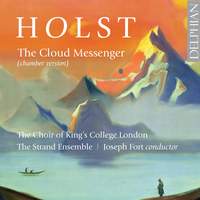

Hitherto, The Cloud Messenger has been relatively rarely performed or recorded; one of the obstacles is the extensive orchestration of its original version. Dr Joseph Fort, Director of Music at King's College London, has produced a new chamber arrangement of the cantata, and recently recorded it for Delphian with the choir of KCL and the Strand Ensemble. I spoke to Joseph about this captivating work, and the story behind it.

The booklet notes accompanying this recording hint that Holst’s period of interest in Indian legends and literature was cut short by the unfortunate circumstances surrounding the premiere. Do you think the break really was this sudden, or was Holst already starting to strike in new directions even before that?

It’s certainly no exaggeration to say that the ‘failure’ of this premiere really put Holst into a deep depression. He went on holiday with Arnold Bax and Henry Balfour Gardiner shortly afterwards, and Bax reported that it was almost impossible to get him to speak. He had spent seven years working on this piece, after all! But it’s not as if he had been working exclusively on Indian-influenced music during this period: he had also written a number of partsongs in the early 1900s, which have quite different themes. So I guess we might see it more as a shifting of focus, rather than a clean break.

Many works seem to have suffered from lacklustre premieres leading popular opinion to conclude (often wrongly) that the work itself was at fault. Is there any indication that critics in Holst’s time were able to see past the poor execution of the first performance and recognise the quality of the music itself?

Definitely. In particular, Holst’s friend W. G. Whittaker really championed Holst’s choral works in the north - especially in Newcastle, where he conducted a choral society. As Daniel Jaffé writes in our CD notes, Whittaker conducted several further performances of The Cloud Messenger, in an arrangement for piano, string quintet, timpani and percussion. Down south, in Bournemouth, another conductor friend Dan Godfrey was programming a lot of Holst’s orchestral music around this time, and Henry Balfour Gardiner (who had conducted the premiere of The Cloud Messenger) was still advocating for Holst’s music.

There are a few passages where Holst uses audibly Indian-inspired scales and melodies reminiscent of raga modes. Is this merely a sprinkling of superficial colour in keeping with the legend’s setting, or is there evidence that Holst was experimenting with incorporating Indian Classical influences into his style on a deeper level?

As Raymond Head has shown in his book Holst and India, Holst’s interest in Indian culture, Sanskrit literature, and Buddhist religion ran deep, and influenced much of his outlook on life - beyond his music. But I think it’s fair to say that Holst was extremely limited in what he’d have been able to find by way of fifth-century Indian music, to model his own on! He seems to have really engaged deeply with all the literature he could find, and the moment in The Cloud Messenger when we hear ‘the singing maidens chanting the praises of their Lord’ is certainly a sincere attempt at creating something that conveys at least a sense of what Holst imagined this music to sound like.

When you came to arrange Holst’s original for smaller forces, was the specific fifteen-player ensemble on this recording always the intention from the outset, or did the number of players in your arrangement grow and shrink during the process?

The arrangement was partly inspired by Robert Kyr’s recent arrangement of The Lovers by Samuel Barber, for a similar combination. I set out with fifteen players in mind but feeling flexible - thinking that I might need to add one of two more (and even a piano, if necessary). But in the end it stayed at fifteen! The biggest challenge was the percussion: in the original, some of the climactic moments have three players playing at least three instruments simultaneously. I managed to keep it to one player - but they need to be rather athletic at points!

Some unkind critics at the time suggested that The Cloud Messenger suffers from being merely a series of scenes and episodes without a real narrative. Do you think there’s any merit to this criticism?

Yes: it is a series of scenes/episode - quite film-like in that sense. But there’s certainly a narrative, and a really beautiful one: the story of the cloud’s journey up into the Himalayas, building to its arrival in the chamber of the yaksha’s wife. More importantly, though, Holst sews the whole thing together through his use of several Leitmotifs, which run throughout the 45-minute piece as several threads. When you start to understand the associations that these each carry, I think they bring an additional layer of meaning. For instance, Holst actually omitted a large chunk of Kālidāsa’s original poem at the start of the piece (pertaining to the yaksha’s banishment), but I think references throughout the substantial prelude, in his use and manipulation of the Leitmotifs.

The concluding section of The Cloud Messenger has more than a hint of The Planets about it – do you think there’s a sense in which Holst was trying out ideas which he would use in the latter work just a few years later?

Yes, definitely. You can certainly hear ‘Neptune’ in there, in particular, at the end of The Cloud Messenger. I love the way you can hear this little forecast of what was to come!

Beyond stemming from roughly the same period in Holst’s career, is there anything else linking the five partsongs to The Cloud Messenger?

When you have one main piece on a disc, it can be such a challenge to work out what to put with it. I must have gone through about a hundred different possibilities with this one, and not just Holst’s music. In the end I thought that the Five Partsongs (Op. 12) would be the best fit, not least because of their focus on the theme of love. Holst composed them shortly after his marriage to Isobel, and just before his delayed honeymoon to Germany (which seems to have involved going to a lot of Wagner operas!).

The Choir of King's College London, The Strand Ensemble, Joseph Fort

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC