Interview,

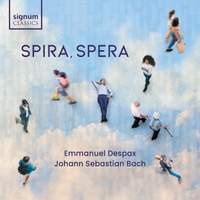

Emmanuel Despax on Spira, Spera

French pianist Emmanuel Despax has tended hitherto to record mostly Romantic repertoire – including Chopin's Préludes, Franck's Variations Symphoniques and a double-bill of concertos for Hyperion's Romantic Piano Concerto series. His latest release, though, sees him turn to an area of the repertoire that can still spark controversy today: piano transcriptions of the works of JS Bach.

French pianist Emmanuel Despax has tended hitherto to record mostly Romantic repertoire – including Chopin's Préludes, Franck's Variations Symphoniques and a double-bill of concertos for Hyperion's Romantic Piano Concerto series. His latest release, though, sees him turn to an area of the repertoire that can still spark controversy today: piano transcriptions of the works of JS Bach.

It's an album conceived at least in part as a personal musical response to the devastating fire that severely damaged Paris's iconic Notre Dame cathedral in April 2019, from which it takes its title. I asked Emmanuel about the inspiration behind the album, and the varied approaches to transcription that it encompasses.

You mention the title of this album having originated in your reaction to the Notre Dame fire of 2019 – was this a concept you were already mulling over, or did it spring into your mind purely in response to the fire?

The title was a genuine reaction upon seeing the great Parisian cathedral engulfed in flames. I think it is one of these places that belong to all of us, humanity’s heritage. "Spira, Spera" or "Breathe, Hope" is a quote from Victor Hugo’s novel: The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. My maternal grandfather, Jacques Charpentreau, was a poet, and introduced me to Victor Hugo early on as a child. I quickly became a huge admirer of his work. When I saw the great cathedral in flames, a lot of thoughts came pouring in my mind, the beauty of the place, my grandfather, wonderful childhood memories growing up in Paris and attending Bach organ concerts in the cathedral. Of course I have always loved and played Bach transcriptions, but I knew then that this is what I wanted to record next and dedicate a complete album to Bach’s legacy.

This album features the arranging talents of many different musicians – Saint-Saëns, Busoni, Siloti, Liszt, Szántó and Hess. When you come to play them, how different does each arranger’s approach seem to you as a pianist – how much does their own style come through in the arrangement?

It is fascinating to get a glimpse into the transcriber’s mind, and see how each one handles the transcription differently. At one end of the spectrum, we have Liszt, who, perhaps as a show of respect, is unusually sober in his approach and respectful of the original text. Coming from one of the biggest piano virtuoso that ever lived and a master transcriber, this is indeed I think his own personal way of showing how much he revered and loved Bach’s music. Schumann once said that “Music owes as much to Bach as religion to its founder.” I think we can safely assume that Liszt felt the same way.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have Busoni, who takes Bach’s original text, and treats it as the foundation upon which his imagination can build an entire cathedral.

In all cases though, my approach is the same: I try to remain true to the essence of the original work, while embracing the transcribing style of each composer.

The notes accompanying the album include a lengthy defence of the whole idea of performing transcribed versions of Bach’s works, pointing out that for most of musical history this practice was accepted and expected. Yet even today, many people harbour disdain for transcriptions and see them as polluting the “purity” of the original. How did this mindset first originate?

I have to admit that I have trouble thinking about music with this kind of mindset. I always remember Stravinsky’s words: “The trouble with music appreciation in general is that people are taught to have too much respect for music, they should be taught to love it instead.”

I guess what you are referring to would have started around the late 1950s with the historically informed performance movement. I have no issues with stylistic awareness and respect for the score, on the contrary, as a musical grandchild of Claudio Arrau, I can assure you that this is at the forefront of my mind and interpretative concerns - but these debates are, in my opinion , secondary to the talent, power of conviction and imagination of the performer. Let’s take the famous Menuhin/Enescu recording of Bach's Double Concerto in D minor for example, or Gould’s last Goldberg Variations recording, or Busoni’s own recording of his Bach Chaconne transcription. All these recordings could be considered, from a scholar’s point of view, stylistically “wrong”. Yet they remain, in my opinion, some of the most powerful interpretations of these works on record to date. That is not to say I don’t love hearing Pierre Hantaï’s Goldbergs on the harpsichord, or Andreas Staier’s late Schubert sonatas on a fortepiano for example - both have moved me to tears with their performances.

The second one plays Bach on a modern piano, one is already transcribing his music to some extent. And even if one plays on a period instrument, our twenty-first-century ears are no longer receiving this music in the same way. Therefore, I would argue that it is all transcribed, and it is just a question of degree.

Who can say how Bach would have composed on the modern piano we know today - would he not have taken advantage of everything it has to offer: dynamics, pedalling? Playing “unchanged”Bach on the piano poses all sorts of problems, the piano cannot rival the harpsichord when it comes to ornementation, chord spreading, clarity and lightness of textures, and articulation; and generally when pianists try to imitate the style of the harpsichord, it is to disastrous effects.

Transcribed Bach solves a lot of these issues. I find that in many ways, the modern piano is particularly suited to reproducing organ sonorities and textures, as well as the acoustics of a church.

Although he was by no means inactive as a composer in his own right, Ferruccio Busoni is well-known (perhaps even primarily known) as a transcriber of Bach, chiefly through his monumental “Bach-Busoni Editions” covering nearly four decades. How and why did he come to devote so much energy to Bach’s works?

Busoni revered Bach, and considered him to be the foundation of music and the greatest of all composers. I think Busoni transcribed Bach’s work as a tribute, an hommage to this most beloved composer and his wonderful music. He takes huge amount of freedom doing so, but the essence and spirit of the original music remains intact.

You include on this album two imposing arrangements by Theodor Szántó, of the Passacaglia and Fugue BWV582 and the Fantasia and Fugue BWV542; neither has been recorded before. Who was Szántó and why has our own time barely heard of him and his music?

Szántó was a Hungarian pianist and composer, born a few years after Busoni. He actually became a student of Busoni for a few years. He most notably helped Delius rewrite the piano part of his piano concerto (the work is dedicated to Szántó), and later played the concerto at the Proms. He, like Busoni, became very interested in Bach transcriptions. The piano repertoire is vast, and we pianists tend to play a small fraction of it. One could spend an entire life time studying the “core repertoire”. That is a lucky situation to be in of course. But as an interpreter, I love exploring unchartered territory from time to time. This was particularly exciting, as the Bach works themselves are very famous.

It is clear from his writing that Szántó was a formidable virtuoso, stretching the piano to its limits. From a technical standpoint, his transcriptions are like Busoni on steroids. From a compositional standpoint however, he takes a rather Lisztian respectful approach: Harmonies are unchanged, and polyphony is unaltered. But unlike Liszt, he is completely uncompromising, making you play every note of the organ original and more, even when one would think it is physically impossible. One just needs to hear the famous Liszt arrangement of the same Fantasia and Fugue in G minor in comparison, to see just how uncompromising Szántó can be. I think his transcriptions are remarkable and I hope that this recording will contribute to making them more established.

Emmanuel Despax (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Emmanuel Despax (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Emmanuel Despax (piano), Orpheus Sinfonia, Thomas Carroll

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Emmanuel Despax (piano), BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Eugene Tzigane

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC