Interview,

Mark Bebbington on Poulenc

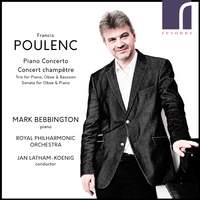

The British pianist Mark Bebbington's recordings of Poulenc's Piano Concerto and Concert champêtre last year were described by Gramophone as 'rich in sensual gratification and intellectual nourishment', and the sequel (recorded under COVID-compliant conditions shortly after the first disc was released) is no less rewarding, featuing witty, mercurial accounts of Aubade, Le Bal masqué, the Flute Sonata and the Sextet. I spoke to Mark over Zoom about how his affection for Poulenc's music was inspired by his early studies with one of the composer's great friends and champions, why the piano works perhaps don't receive the attention and exposure which they deserve, and how Aubade turned out to be the perfect 'lockdown piano concerto'...

The British pianist Mark Bebbington's recordings of Poulenc's Piano Concerto and Concert champêtre last year were described by Gramophone as 'rich in sensual gratification and intellectual nourishment', and the sequel (recorded under COVID-compliant conditions shortly after the first disc was released) is no less rewarding, featuing witty, mercurial accounts of Aubade, Le Bal masqué, the Flute Sonata and the Sextet. I spoke to Mark over Zoom about how his affection for Poulenc's music was inspired by his early studies with one of the composer's great friends and champions, why the piano works perhaps don't receive the attention and exposure which they deserve, and how Aubade turned out to be the perfect 'lockdown piano concerto'...

Although Poulenc himself adapted (and even recorded) the Concerto champêtre for the piano, it’s still more commonly heard in its original incarnation for harpsichord: how well do you feel it translates?

Even the Piano Concerto is so rarely heard, but the Concerto champêtre in some ways is a much finer work from a musical point of view, and the prospect of recording it in this alternative version immediately appealed to me. The idea came from our conductor, Jan Latham-Koenig, who’d done both versions of it quite a bit in the past: he told me he feels it works much better for piano than it does for harpsichord, and I have to say that on balance I agree with him. It becomes a slightly different piece: when you hear Poulenc’s own recording of it (with Dimitri Mitropoulos and the New York Philharmonic), he’s clearly relishing the textures and the expressive possibilities of the piano in a way that completely transforms it from a harpsichord concerto.

It throws up some fascinating conundrums: in passages like the opening of the last movement you’re actually directly imitating the harpsichord (you have to in order for it to make any musical sense), but elsewhere there are opportunities to make these fantastic pianistic legatos which sound completely different from the harpsichord.

Do you have a preference as to what model or vintage of piano you use for Poulenc, or indeed for this piece in particular?

No, I’m not one of these pianists that’s obsessively in pursuit of the perfect piano: I think that all of the major piano manufacturers have particular qualities that suit the strengths of most repertoire. In this instance we recorded on a wonderful Steinway, and I thought it worked very well.

Do you have a direct lineage back to Poulenc via any of your teachers and mentors?

I studied in Italy and in Paris with the great French-Italian pianist Aldo Ciccolini, who was of course well known for all of his EMI recordings of French music, and he introduced me to Poulenc’s solo piano works – I learned Napoli with him, which is a wonderful showcase. He knew the composer very well: Poulenc was going to write a third piano concerto for him, but alas Poulenc died before that happened.

So it was Aldo who opened my eyes to the joy of the music, and also to the fact that French piano music of that era of course is dominated by Debussy and Ravel…I think part of the reason why the Poulenc piano works have been overshadowed by those two composers is that many of them are essentially rather small-scale and perhaps better suited to a salon rather than a large concert-hall: there’s a certain intimacy about them that would be lost in venues like the Queen Elizabeth Hall or the Festival Hall (it’s perfect for the Wigmore, of course!). I believe that’s one of the reasons why this music has been neglected, frankly, by so many pianists - but it’s just glorious stuff.

Poulenc described Le bal masqué as ‘100% Poulenc’ – what precisely do you think he meant by that, and do you agree with his self-assessment?

Le bal masqué is one of his most complex and contradictory works. With that remark I think he was referring very much to the last movement, which is in a sense quintessential Poulenc in its light-hearted feel; it also takes a punt at something that comes close to being commonplace or even vulgar, which was a very important part of Poulenc’s make-up and his music-making. He could compose a theme that we think of as distinctively ‘French’ very easily – that finale is a kind of Gallic version of Knees Up, Mother Brown, really, and it’s a fantastically exuberant way of finishing this cycle. But the piece before, La dame aveugle, is a setting of an almost Expressionist text: if you listen to even three bars of that you could almost be in the world of Webern. It’s so strikingly different from the surrounding movements, but in so much of his music we find these abrupt juxtapositions of mood with no real preparation – the Piano Concerto, for instance, is full of similar contrasts. They’re a hallmark of his style, but can throw the listeners a bit!

I think it is ‘100% Poulenc’ in a way, but not in the sense that he meant of being full of Gallic charm: there are strong elements of that, of course, but it’s also much more strident music at times than we usually associate with this composer. And that was something that Jan, our conductor, was particularly keen to get across – there has to be a kind of biting sound from the woodwind, which can in all honesty make it something of an uncomfortable listen, but it’s also part of what makes the piece so intriguing.

The Sextet, which also features on the album, was very poorly received at its premiere – do you think there were similar elements at work there in terms of the stylistic contrasts wrong-footing audiences?

Yes, I do. I was listening to some of the session-tapes recently, and when you hear the main theme of the Allegro which he then picks up at the end, again it’s very close to an almost atonal world – certainly far more akin to the language of Stravinsky and Prokofiev than we might naturally expect from him. He also employs a rather wonderful technique which was something which he learned from the Germanic tradition: the idea of a transformation of themes. He translates the very jagged theme that begins that Allegro into something incredibly beautiful for the piano and oboe in the middle section, and unless you’re really listening hard you can’t tell that it’s actually the same melody in massive diminution. But it’s only when we get into the slow movement that we come close to that quintessential lyricism that we tend to associate with Poulenc.

We accept the Sextet now as one of the masterpieces of the twentieth-century chamber-repertoire: all of the RPO players on the recording had played this piece many times before, and for the horn-player in particular it’s notoriously difficult but also rewarding. So it’s become part of the canon, as it were, of popular chamber works, but it’s taken quite a long time to get there because the musical language is really quite forward-looking for the time when it was written.

What inspired you to group these particular works together, and is there more Poulenc in the offing from you?

For me all of these works are now indelibly associated with the major lockdown of last year from March onwards: Aubade is scored for eighteen players plus piano and conductor, and it was the biggest work that could be fitted on stage at Cadogan Hall under the circumstances: Health and Safety regulations could cope with nineteen performers, but no more! It sort of became ‘Aubade: The Lockdown Piano Concerto’ in the sense that we could do it comfortably with social distancing, and we decided to do Le bal masqué while we were there; Roderick Williams (like most of us at the time) was readily available for that, and then a little later we did the Sextet. With everything that was going on it seemed natural to make this recording a kind of grouping of the chamber works, and I’ll explore the solo piano works further down the line.

We’re having a little bit of a break from Poulenc for the next CD and looking at some more neglected French composers, in particular Déodat de Séverac, who is one of my great enthusiasms and wrote wonderful music for the piano. And there’s also some Messiaen in the pipeline…

Mark Bebbington (piano), Emer McDonough (flute), Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Jan Latham-Koenig

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Mark Bebbington (piano), John Roberts (oboe), Jonathan Davies (bassoon), Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Jan Latham-Koenig

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC