Interview,

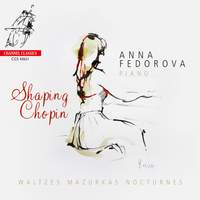

Anna Fedorova on Shaping Chopin

The catastrophic impact of various COVID-19 lockdowns on music and musicians is now well-documented, and continues to be felt strongly around the world even as those lockdowns themselves are eased or lifted. Pianists were perhaps less completely cut off from the ability to make music than were other performers, with an extensive solo repertoire to draw on during even the most severe isolation measures.

The catastrophic impact of various COVID-19 lockdowns on music and musicians is now well-documented, and continues to be felt strongly around the world even as those lockdowns themselves are eased or lifted. Pianists were perhaps less completely cut off from the ability to make music than were other performers, with an extensive solo repertoire to draw on during even the most severe isolation measures.

Ukrainian pianist Anna Fedorova was one such musician – cut off from friends and family, and in particular her parents in Kiev, she found herself drawn above all to the music of Frédéric Chopin, and has now released an album of his solo piano works that is deeply shaped by this experience. I spoke to Anna about this album, and the role Chopin's music played in her own experiences of the pandemic's early months.

Like many people over the past eighteen difficult months, you’ve found comfort in music. There are plenty of composers whose music could have served this kind of “therapeutic” function – what drew you particularly to Chopin?

Indeed, we as musicians are lucky, as even with all the restrictions and isolation we faced a year and a half ago, one thing we could never lose was music. Of course Chopin was not the only composer whose music I was playing during the lockdown. I and my husband (Nicholas Schwartz, a double bassist with the Concertgebouw orchestra) found ourselves playing a lot of chamber music during the lockdown, which also had an almost therapeutic effect – being able to have a real live contact and make music with our friends was very important during this time. We did many streams and online festivals, which also helped us to keep in touch with our audiences, even if only digitally.

But in terms of the time I spent at the piano alone, yes, Chopin’s music dominated. There was a personal reason for that: As I was separated with my parents for all this time without possibility to travel (they were stuck in Kiev, Ukraine, where the coronavirus situation was very bad), I was thinking and worrying about them a lot. Both of my parents are wonderful pianists and piano professors, they were my teachers for many years, and Chopin’s music always occupied a very important place in my repertoire and in my heart since I was a child. I always felt very connected with his spirit, his incredibly beautiful singing melodies and harmonies, the constant presence of a certain melancholy and nostalgia in his music, his tenderness and hopeless romanticism, but at the same time inner power and passion. All of this resonated very strongly with my emotional state during that time, and by playing some of the Chopin’s pieces I also felt as if I was getting closer to my parents and to my childhood, as this was the time I was working with them on so many of the pieces which ended up on the album.

You mention the vivid imagery conjured up by the works you’re playing here. Do you think we should view Chopin as a creator of musical sketches akin to Liszt or Debussy, even if his pieces mostly lack similarly descriptive titles?

Chopin was against concrete descriptive titles of his pieces, leaving the music to speak to the listener and to the performer on its own. But of course it doesn’t mean that his music is lacking in imaginary and atmospheric content. It’s very individual for everybody what they hear and find for themselves in each of his miniatures. Sometimes it’s just a mood, atmosphere, sometimes a little story, it could be a scene from the ball, or an imaginary sketch. It’s interesting, for instance, that Debussy put the names for his preludes at the end, as if to only suggest a title, so as not to take away personal approach and imagination of the performer. Liszt on the other hand was almost always giving titles to his works, as he was an ambassador of programmatic music, as well as of combining the arts. Many of his pieces, for instance, have a connection to literature, sculpture, or portraits of historical figures. We can also feel a strong connection with nature. Many of his titles give us almost impressionistic images such as “Feux follets”, “Harmonies du soir” and so on.

In the 1830s there seems to have been quite a community of Polish emigrés in Paris, of whom Chopin was one. How much do you think his artistic success relied on the support of that circle?

Chopin was getting support from various people of different nationalities, but also of course Poles. For instance, his first concert in Paris was organised with the help of Ludwik Norblin, a cellist of Polish origin, as well as the pianist Friedrich Kalkbrenner.

The Mazurka – a musical form strongly associated with Chopin – is also uniquely Polish, coming from the Masuria region. Were other composers writing or performing Mazurkas before Chopin made them a popular kind of miniature?

Yes, mazurkas were written before Chopin, and also for the piano. For instance, Józef Elsner (Polish composer and Chopin’s teacher of composition), composed two rondos a la mazurek back in 1808, and Maria Szymanowska wrote a large number of mazurkas for piano which were published in 1825, when Chopin was just 15 years old. But again, Chopin brought the genre of Mazurkas to completely different level and introduced it to the whole world.

John Field, who “invented” the Nocturne, seems not to have quite known how to develop it and had little success. How much do you think Chopin’s (far more popular) Nocturnes owe to Field?

We all are very grateful to John Field for inventing such a beautiful, romantic genre as the Nocturne. I think this genre was very close to Chopin’s nature, he loved it and developed it in accordance with his own talent, making the borders broader, the melodies more flexible and improvisatory, the dramaturgy richer and the structures more complex. Apart of the beautiful singing melody with accompaniment his nocturnes also have elements of other genres, such as polonaises, Mazurkas, chorales, marches. I don’t know if Chopin would have invented the genre of nocturne himself if it didn’t exist before – possibly he would, maybe it would have a different name... In any case, he brought the nocturne genre to such an unreachable climax that I can’t imagine a world without them.

Long periods of lockdown and quarantine have led many people to reassessing aspects of their lives, including in music. Did you find that, as you played these pieces in isolation, your approach to them changed?

I think going through this time helped us to feel, and appreciate even more strongly, the power of music and of art in general. People became incredibly creative, making use of technology to keep spreading music and art. It was helping so many people to stay sane, it was giving people hope, it kept us going! I don’t know if I can say that I changed my approach to the pieces I played, but it definitely made me love and enjoy them even more.

It also helped me to explore new depths and emotions in certain pieces I have been playing for my whole life. For instance, I discovered that some of Chopin’s music combines very naturally with poems by my favourite poet Alexander Pushkin, which in a way has a similar emotional effect on me. During the lockdown Nicky and I got into making music videos, where we tried to visualise some of the associations and images which the music provoked in our minds. Some of them we made in combination with paintings, some of them with poems. One of the videos was of Chopin’s Waltz Op. 64 No. 2, in combination with a beautiful poem by Alexander Pushkin; they seem resonate magically with each other.

Anna Fedorova (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC