Interview,

Chen Reiss on Fanny Hensel

Although Fanny Hensel's lieder and chamber works have gradually begun to receive the recognition they deserve over the past decade or so, her larger-scale compositions still remain woefully under-represented on disc and in the concert-hall; the warmest of welcomes, then, to a new recording from Israeli soprano Chen Reiss, Daniel Grossman and the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich, which features the barnstorming dramatic cantata Hero und Leander, an aria from her Lobgesang (which predates her brother's composition of the same name by nearly a decade), and a selection of songs in new orchestrations inspired by the colours and textures which Hensel deploys in her writing for voice and orchestra elsewhere.

Although Fanny Hensel's lieder and chamber works have gradually begun to receive the recognition they deserve over the past decade or so, her larger-scale compositions still remain woefully under-represented on disc and in the concert-hall; the warmest of welcomes, then, to a new recording from Israeli soprano Chen Reiss, Daniel Grossman and the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich, which features the barnstorming dramatic cantata Hero und Leander, an aria from her Lobgesang (which predates her brother's composition of the same name by nearly a decade), and a selection of songs in new orchestrations inspired by the colours and textures which Hensel deploys in her writing for voice and orchestra elsewhere.

I spoke to Chen last month about how this project introduced her to Hensel's remarkable (and still largely underappreciated) gifts as an orchestrator, the composer's complex relationships with her brother Felix and with their Jewish heritage, how her family obligations and social class restricted her musical activities and public profile, and how one of her songs became a firm favourite with an especially high-profile female contemporary...

What prompted you to explore Fanny’s works for soprano and orchestra?

Sometimes in life things find you rather than you finding them, and often these are the best projects. Last year Daniel Grossman, the conductor of the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich, phoned to invite me to sing a big concert in Munich with them celebrating 1700 years of Jewish life in Germany. That’s a pretty big deal, and it attracted a lot of media interest, not only from music magazines but from the German press in general. Daniel asked me to sing an aria for soprano, choir and orchestra from Fanny Hensel’s cantata Faust, which I didn’t know at all: I knew her songs and piano music, but I wasn’t aware that she also wrote orchestral music.

When Daniel and I started looking into Fanny’s compositions for soprano and orchestra, we discovered so many possibilities that I suggested we record an album: as far as I know, this music has never been collected in one place before in an homage like this. And through this research I came to realise that she’s actually a very dramatic composer and an extremely skilful orchestrator: we know that she was a fine pianist and singer through her songs and solo piano works, but her sense of theatre and her ear for different orchestral colours and textures is extraordinary.

Had she not been a woman, I believe she would have written at least one of the great operas of the first half of the nineteenth century. In these larger-scale, more complex works you see that she was inspired not only by her brother Felix but also by Beethoven, Brahms and more Romantic composers; parts of Hero und Leander even remind me of Wagner. That’s what gave me the courage to propose having the songs orchestrated for the recording: there’s so much drama and poetry in the music as well as in the texts that they cry out for it. I strongly feel it’s about time that we give this composer the stage that she deserves.

How much do you feel Fanny was eclipsed by Felix during her lifetime?

There’s no doubt that she was just as talented as her brother, if not more so – their piano and composition teacher Carl Friedrich Zelter mentions her in two letters to Goethe, saying that she’s quite special. We learn more about her talent from other people’s writings about her than from her own correspondence: in her letters and diaries she doesn’t write so much about her musical world, because she took her duties as a wife, a mother, a sister and a daughter very seriously. Fanny wasn’t poor, like Clara Schumann: she came from a very distinguished, high-society family, and this was her corset in a way – she was very dutiful and played by the rules, rather than dedicating her life and herself to her art. Her father and brother didn’t support her ambitions as a composer, so she didn’t go against them and she accepted it.

Was her husband more supportive than her father and brother?

They had a very happy marriage, and that’s why it’s a little bit disturbing when people call her ‘Fanny Mendelssohn’: they do that to make the connection to Felix, but she was a composer in her own right who proudly carried the name ‘Hensel’, so I prefer to refer to her as ‘Fanny Hensel’ rather than ‘Fanny Hensel Mendelssohn’ or ‘Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel’. She and Wilhelm Hensel were genuinely in love, and he was also a famous artist: he painted her and their son Sebastian. It’s difficult to judge exactly how supportive he was, because it was simply the social norm that women of that class didn’t have a career – otherwise she could’ve been a famous pianist and toured Europe like Clara Schumann did, but for a woman of Fanny’s milieu that would have been seen as a faux pas.

I think Wilhelm was more supportive than her brother and their father, but those two were very dominant in her life – her relationship with Felix was very loving, and there was a great deal of mutual respect. Fanny was his confidante and greatest advisor: he never asked advice from other people but he always showed her all his pieces, so there was definitely a lot of trust between them. And he had no problem publishing her pieces in his name, but when she finally published her own Op. 1 under her name he was somewhat unhappy at first...

Some of the material I’ve read suggests that Felix actually believed he was doing her a favour: he thought it would distract her from her family duties had she published things under her name and had to spend more time promoting her works and talking with publishers. And I don’t think we can accuse him retrospectively: men at that time genuinely believed that it was impossible to be a family woman and a career woman. Today we know that isn’t true, but back then they thought that one would interfere with the other.

But the fact that theirs was a loving, close relationship was why it was important for me to bring the two of them together on the CD. I think Felix was very dependent on her emotionally, and when she suddenly died of a stroke at 41 he was heartbroken and depressed; he died a few months later himself, so I definitely think her death is what broke his spirit.

How recently did a clearer picture of Fanny’s output begin to emerge?

The research began around the 1990s, I think, so it’s definitely pretty recent. It was only in 2010 that we found out that the Easter Sonata was actually by Fanny – up until then it was attributed to Felix. But there’s a nice story about one particular song which dates from their lifetime: Felix toured to London on many occasions, and on one of them he met Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace. She was very excited and she asked him to play and sing her favourite song of his, Italien’…and he actually confessed that Fanny wrote it! Queen Victoria also had to struggle as a female in a male-dominated world, so I’m sure she must’ve been very pleased to learn that her one of her favourite songs was by a female composer!

How widely did Fanny travel?

I know she travelled in Germany and spent a while in Paris, but I’m not sure if she made it to England. Certainly she didn’t travel as much as Felix, because he was a very famous conductor and he was also busy rediscovering the music of JS Bach and bringing that to the world; Fanny was married with a child and did a lot of teaching, so she was more bound to Berlin.

Did Fanny have many strong female role-models in her life?

First of all I think her mother: she was her first piano-teacher and was supportive of her as a pianist and composer, but even the mother had to keep her voice down in that very patriarchal society. She also had two aunts who were well-known pianists, and there was Clara Schumann too, so she was definitely surrounded by some strong women - but if we compare it to our times it’s nothing!

How much do you feel that Fanny’s Jewish identity informed her music?

In our booklet-note we focus on the Jewish Question and how Jewish Fanny and Felix felt, because in a way they were torn between two worlds. They were born into an aristocratic Jewish family – their grandfather Moses Mendelssohn was a very eminent philosopher who was known as ‘The Jew from Berlin’, as he was probably the most famous Jewish figure in the city at the time. The family were very proud of Moses, but on the other hand Fanny and Felix’s father decided to convert to Christianity: Fanny was 11 when she was baptised, which meant changing her name as well as her religion.

That’s a huge thing for a child as smart as her to process, and I think Fanny felt it even more than Felix: they were torn between admiring their grandfather and honouring their father’s decision to convert. Today it wouldn’t be necessary because we’re much more open and accepting of other religions and cultures, but back then in Germany the Jews so wanted to assimilate that they felt themselves to be more German than Jewish, and they thought that by converting they would be accepted by society. Of course today with our knowledge of how things developed in the twentieth century they made a mistake thinking they’d be accepted. They were not.

This was my first collaboration with the Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich, and I learned so much from them: even as a Jew and as an Israeli I’m so familiar with Christian music and I have (should I say had) less knowledge of Jewish music, but through them I was introduced to some composers and pieces which I didn’t know before.

Fanny did write cantatas on themes from the Old Testament (Job, for example), but in the pieces that we recorded there are no Jewish themes in either the text or the music: she’s not using Jewish keys or Jewish motifs. I cannot say that she was a Jewish composer per se– it’s not like the music of Mahler, for instance – but the whole question of what IS Jewish music is a massive one! Non-Jewish composers like Shostakovich or Prokofiev wrote music using themes from Jewish prayers and liturgy, so their music sounds more Jewish to me than the music of Felix and Fanny.

They were both so fascinated by the music of JS Bach that if anything I would say that they are closer to Christianity in their writing; indeed we included the overture and an aria from Fanny’s Lobgesang, not to be confused with the one by Felix! There you absolutely see her fascination and appreciation and understanding of the writing of JS Bach. She’s not using Bach’s language, but you see how skilful she is in counterpart and harmonic development and the melodic line; she always has her individual touch, which I would describe as sweetness but not kitsch. It’s just the right amount of sugar!

Do you think Fanny and Felix diverged in terms of their musical language, especially later in life?

I think that had she lived longer or written more dramatic works she would have gone in a more Romantic direction than Felix – to me Felix always has half a foot in the Classical world, especially in something like A Midsummer Night’s Dream, whereas Fanny leant more towards the world of Brahms. There is one song in particular on the album, ‘Dämmrung senkt sich von oben’, which so reminds me of Brahms in terms of its harmonic language and colours, and her ‘Die Mainacht’ is on the same text as the famous setting by Brahms.

I hear a lot of North German musical language in her pieces, and when she’s describing nature it’s definitely a North German view of nature - with the exception of ‘Italien’ of course, which to me is a joke! Northern Europeans have a very romanticised way of describing Italy, even if they’ve never been there: Italy is the country where the sun is brighter, the sky’s bluer, the green is more green, the herbs smell amazing and everything’s bursting with life. She says ‘Zieh' ich zum Lande der Poesie’ – ‘I go to the land of poetry’ - so it’s a very Romantic way of seeing Italy.

Are there any books you’d recommend to anyone interested in learning more about Fanny’s life and work?

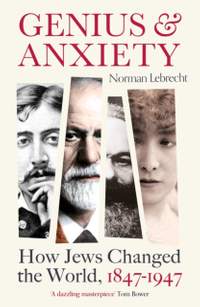

Yes: Norman Lebrecht’s Genius and Anxiety: How Jews Changed The World, which focuses on various Jewish figures from the middle of the nineteenth century through to the middle of the twentieth, and includes a chapter on Felix and Fanny. His style of writing is quite confrontational and provocative, but I found it fascinating. I also found Das Glück der Mendelssohns by Thomas Lackmann (who also wrote the booklet notes for the CD) excellent and very informative, and am currently reading Das Erbe der Mendelssohns by Julius H. Schoeps.

Fanny Hensel & Felix Mendelssohn: Arias, Lieder & Overtures

Chen Reiss (soprano), Jewish Chamber Orchestra Munich, Daniel Grossmann

Available now as a download, and released physically on 25th March.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Norman Lebrecht

Available Format: Book