Interview,

Raider of the Lost Archives - Michael Spyres on Contra-Tenor

As his Gramophone Award-winning Baritenor amply demonstrated back in late 2021, one can always expect the unexpected from American singer Michael Spyres. Having shape-shifted between roles as diverse as Donizetti's high-flying Tonio and Verdi's Conte di Luna on that last album, he devotes the equally ear-opening sequel Contra-tenor to exploring the development of the Baroque tenore assoluto - unearthing virtuosic rarities by composers including Vinci, Sarro, Porpora and Mazzoni (this last including a jaw-dropping three-octave cadenza complete with top G!) along the way...

Fresh from his final performance as Pollione in the Metropolitan Opera's Norma last month, Michael spoke to me about the joy of delving deep into music written for 'the outsiders and the weirdos', why he feels that full-bodied voices have much to offer in this repertoire - and his conviction that an eighteenth-century tenor who's been rather maligned by the history-books 'must've been one of the greatest singers of all time'...

When were the seeds for this album sown?

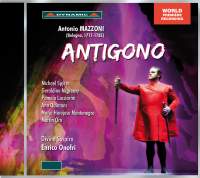

The journey started in 2011, when I sang in the first modern performance and recording of Mazzoni’s 1755 opera Antigono with the wonderful soprano Geraldine McGreevy. It all came about because of Lionel Meunier, who was my room-mate in Belgium at the time; one of Lionel’s friends told him that they were trying to unearth this bizarre piece but just couldn’t find a voice that could manage the title-role, and Lionel thought it might be right up my street. He put me in touch with the Gulbenkian Foundation in Portugal, and when they sent me the music I thought ‘This is perfect! This is the weird crazy stuff that I can actually sing!’.

The role was written for Anton Raaff, a name I only knew as a footnote in Mozart’s biography, where he’s described as this old man who was barely able to sing: he was sixty-six when he created the incredible florid role of Idomeneo, and even though he was apparently past his best by then I kept thinking he must’ve been one of the greatest singers of all time. (If I’m still able to get round ‘Fuor del mar’ when I’m sixty-six I’ll count myself very lucky!). Finding out that he’d also created Antigono twenty-five years earlier blew my mind: I thought ‘There’s this whole genre that nobody knows about - I’m a massive nerd about vocal history and even I don’t know about it!’.

It occurred to me that the only reason we know so much about the great castrati is because of the curiosity of a generation of artists who dug up these crazy pieces and then sang the hell out of them! It started with Russell Oberlin in the 80s, then Cecilia Bartoli and other mezzos got in on the act, then came the countertenors who are also musicologists – today we have a whole crop of them who started ten or fifteen years ago, including people like Franco Fagioli, and they’ve done so much to bring these forgotten stories to light. I thought it would be so exciting to take up the challenge and become like the Indiana Jones of the tenor voice!

How did you set the wheels in motion?

I started having discussions with Baroque experts and throwing out names like Francesco Borosini and Angelo Amorevoli, then I investigated the specific operas which were written for them and tracked down the scores. Seeing that amount of coloratura and long lines laid out on the page was both exciting and terrifying: I’d sing through it and think ‘This is some of the hardest music I’ve ever come across, why has nobody done it?!’. Well, because it’s so freaking hard!

To my knowledge, no one else has really explored the sheer virtuosity of Borosini and John Beard before. Because I’d already traversed the crazy world of French grand opera and Rossini’s opera seria, where the level of virtuosity is just immense, I figured I had a sporting chance of exploring that angle and getting it right! And I would definitely consider this to be part of the same tradition, because I’m not someone who believes that bel canto was just a fifty-year historical period – it’s a school of singing, and the ability and mastery of voice that one needs in the Baroque period is definitely bel canto.

Are there direct links between this generation of singers and those who created the bel canto roles you've explored on previous recordings?

All of the great tenors Rossini was writing for in the 1800s (people like Domenico Donzelli, Andrea Nozzari, Giovanni Battista Rubini and Giovanni David) came from a specific school in Bergamo, and I was intrigued by what they were doing because there’s no way that it just came out of nowhere… It all connects back to those Baroque tenors who were having to master all kinds of crazy fioritura and staccato fireworks in order to compete with the castrati.

And it was actually the castrati who taught them those tips and tricks in the first place: they were the vocal geniuses of their time, and both Raaff and Amorevoli studied with them. The twist in the tale is that the sheer amount of virtuosity that came out of those two singers was a big part of why the tenor voice eventually supplanted the castrati as the male lead…

I think Amorevoli was especially interesting and versatile: a lot of musicologists would call him the first modern tenor, because he was able to sustain such incredibly long beautiful passages. In modern times composers will write a phrase that’s 7-9 seconds, but in the Baroque period (and Mozart as well, particularly in Mitridate) they lengthen to 16-21 seconds! A lot of this music requires insane amounts of breath-control and agility, but to be able to cut across the horns you also need a certain volume of sound – they had to bring out every trick in the bag!

Flipping back to the present day, do you think there’s still resistance in some quarters to bigger-voiced singers tackling Baroque repertoire?

Baroque can be scary territory for singers with larger voices, but to my mind there’s nothing better in the world than having real meaty, beautiful voices singing this repertoire: if you read just about anything about Handel, for instance, you just know there’s no way he would have gone for straight-tone flaccid singing! Like you guys in the UK, I come from a very rich choral tradition and I have great respect for it - but I do sometimes feel like the choral purists have taken over and laid down the law about what sort of voices are ‘supposed’ to sing music from this era. And I believe that attitude needs to change. Singers in the Baroque era didn’t all have this pure, perfect little sound: of course they didn’t have Wagner or Puccini back then, but people with bigger voices existed and they were obviously singing something!

I really hope this album inspires young singers to dig deep into the forgotten riches of this period, because I genuinely believe that there’s something for everyone: if you have a voice that doesn’t fit into modern conceptions of what a tenor or soprano is, start delving into the Baroque and you’re gonna find something for YOUR voice. If you’re in the club and you’re famous for a specific thing then good for you, but most of us aren’t: we have to find our own way, and artists have always done that throughout operatic history. That’s why these pieces were written: these singers were the outsiders and the weirdos, so hopefully this project will help the next generation to find their own language and embrace the weird!

As someone who’s made your name in nineteenth-century repertoire, how challenging was it to really get to grips with Baroque performance-practice?

The Baroque period is so gloriously pedantic that it’s a bit intimidating: I know that this album will be nit-picked more than anything I’ve ever done, because the people who love this repertoire really know what they’re talking about in terms of style! Fortunately I had some amazing Baroque experts on hand within Il Pomo d’Oro, and when I came to them with some outlandish suggestions for the variazione they’d say: ‘That’s a little too Romantic-sounding - we need to bring it back to the Baroque!’.

You mentioned the sheer technical difficulty of much of this music, but are there other factors which contributed to its neglect on disc and on modern stages?

I was speaking to a musicologist friend in Vienna recently, and he hit me with some extraordinary statistics: something like 40 000 to 50 000 operas have been composed throughout history, but at any given period we’re only aware of maybe 15 000 of them. That seems like a staggering number, but it all adds up when you think about it. Over a period of 400 years you had some of the greatest minds and characters throwing their hat in the ring to compete in this art-form - especially in the Baroque period, when operatic success often meant considerable amounts of money and fame. You have people like Mazzoni who was very famous in his time and wrote dozens of operas, but because he was a court composer they’re all sitting in an archive and unless someone actively goes looking for them nobody’s going to realise just how prolific and inventive he was…

How did you decide on the sequence of composers on the album?

I really like to show people the lineage of the vocal writing, which is why this album and Baritenor are programmed in absolute chronological order. When I started looking through the pieces it was very evident that at the end of the 1600s there were two distinct schools: the French school and the Italian school, so I thought it would be good to establish that with Lully and followed by Handel (in Italian mode) and Vivaldi and then see it morph a bit.

Rameau was the first composer who really understood how to fuse the two styles, I think. Lully is wonderful at the declamatory stuff that was so popular with the French - but Rameau knew how to add that extra dash of excitement in order to compete with the Italians, who were coming into French society like wildfire! It’s fun to see the undulation between the two styles across the entire Baroque period, and we finish up with the Piccinni which sounds neither French nor Italian!

A little bird (Christophe Rousset!) told me you have another album in the works which will focus on forgotten nineteenth-century repertoire…

The idea is to explore some of the people who existed in Wagner’s shadow, because even though a huge amount has been written about Wagner and his influence there’s very little about the composers who influenced him. I think that’s partly because he was such an incredible, prolific narcissist that he rarely acknowledged his debts to other composers: when I read his writings I go ‘Hold on a second, my friend - you did a lot, but you didn’t invent the world!’.

In reality, he went through so many different phases of writing and influences, and Auber, Halévy, Marschner, Méhul, Weber and Spontini are all part of the mix: so often I’ve listened ‘blind’ to something by these composers and thought ‘Oh, I don’t know this Wagner piece…’ only to realise it predates him by fifteen years! Of course he was an absolute master in bringing all of these ideas together, but it’s fun to see the lineage.

I’m especially excited that we’re including an aria from Spontini’s Agnes von Hohenstaufen, which barely anyone’s ever heard: there’s one recording with Corelli singing in Italian, but we do it in the original German. It’ll be released next spring or summer, I think – we’ve yet to name it, but I keep returning to the fact that Wagner’s nickname was ‘The Sorcerer’...

Speaking of titles, what’s the story behind 'Contra-tenor'?

The title’s a little tongue-in-cheek: historically, the Brits would sometimes refer to countertenors as ‘contra-tenors’, but really it’s a play on words because this music goes against all your ideas of just holding one high note like you do in the church tradition! And there’s a certain symmetry with Baritenor, which I thought was nice…

I loved the idea of trying to make it look like an old 60s Sinatra or Lanza cover, but I just can’t take myself seriously so I did one straight-faced pose and the rest where I’m kind of laughing at myself - all very meta-meta! The Baroque period was this incredible period of flourishing of art and culture and general zaniness, so it felt right to throw a bit of character in there.

Michael Spyres (tenor), Il Pomo d’Oro, Francesco Corti

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC, Hi-Res+ FLAC

Michael Spyres (Antigono), Geraldine McGreevy (Berenice), Pamela Lucciarini (Demetrio), Ana Quintans (Ismene), Maria Hinojosa Montenegro (Clearco), Martin Oro (Alessandro)

Orchestra Divino Sospiro, Enrico Onofri

Available Formats: 3 CDs, MP3, FLAC