Interview,

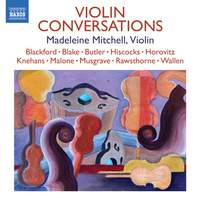

Madeleine Mitchell on Violin Conversations

I spoke to Madeleine shortly before the album's release about how some of these pieces (and the friendships behind them) came about, what sparked her love of contemporary music, and how the recording of Thea Musgrave's Colloquy which features on the album led to a delightful lunch-date with the 95-year-old composer in New York...

Has commissioning new music always been a passion?

This idea of violin-composer collaboration has fascinated me since I was a student – I explored it in my Masters thesis, with special reference to Bartók and Szymanowski. I think that Bartók is one of the greatest twentieth-century composers for the violin, and every single piece he wrote for the instrument is dedicated to a different violinist: Jelly d'Aranyi, Yehudi Menuhin, Stefi Geyer, Joseph Szigeti and Zoltán Székely (who arranged the Romanian Dances for violin and piano). Stravinsky and Brahms are also cases in point: they wrote great violin music, but always working with a fine violinist like Joseph Joachim or Samuel Dushkin.

I studied in New York as a Fulbright Fellow, which took me to the Aspen Music Festival where I met Philip Glass and Ned Rorem. Then when I got back from America I was invited to audition for the position of violinist/violist in Sir Peter Maxwell Davies’s Fires of London, which was (appropriately enough!) a baptism of fire – they were a really extraordinary group right at the forefront of new music, and through that I met lots of composers. It was via Max that I met James MacMillan, who later wrote me two pieces, but I think the very first composer I commissioned was Brian Elias: he’d written a piece for the Fires and I asked him to compose something for a South Bank recital I’d won as part of a competition-prize.

I love playing things like the Brahms and Bruch concertos, but I do like the juxtaposition of working directly with composers. For this album it was terrific to record four of the pieces written for me with the composers themselves as pianists: all of them very idiosyncratic!

For instance, I’d premiered Errollyn Wallen’s piece Sojourner Truth with another fine pianist as part of a recital called A Century of Music by British Women, but working on it with Errollyn herself for the recording was a revelation. Towards the end there’s this incredible, slow re-statement of the main theme (which comes from a slave song); Errollyn encouraged me to take even more time and give it even more space so that it sounded more imposing, and I find that sort of feedback really wonderful. It refreshes your approach to the composers who are no longer with us as well. Imagine being able to ask Beethoven ‘Do you really mean that tempo?!’.

What’s the story behind your friendship with Errollyn?

It comes back again to New York, actually. In 2001 we were both called upon to represent the UK in this amazing festival called UKinNY; six weeks beforehand 9/11 happened so suddenly it became a statement of solidarity with America. I was opening the refurbished Bruno Walter auditorium at the New York Public Library at Lincoln Center, and Errollyn was also doing a recital. We stayed in touch and talked about collaborating for years, then at the Royal Philharmonic Society Awards about three years ago I asked her if she had time to compose something for me and it turned out that she did! The piece was written for International Women’s Day, and as Errollyn explains in this video her research led her to Sojourner Truth.

I confess I hadn’t heard of this extraordinary woman before, but she lived a long and remarkable life: she escaped slavery and became a women’s rights activist as well as an abolitionist, and Errollyn thought that by naming her in the title she would be there in perpetuity.

Did other composers featured on the album draw on extra-musical inspirations?

Most of them are more abstract, but one exception is Wendy Hiscocks’s Dry White Fire, which draws on a poem by Mary Gilmore: it’s subtitled ‘An Aboriginal Simile’, which is very evocative. Wendy’s quite a visual person, and having her there for the recording was great because she gave me some mental images that would really spark the imagination.

Howard Blake’s The Ice Princess and the Snowman is the most beautiful little piece: when The Snowman was made into a ballet they felt there wasn’t enough material, so he added this wonderful pas de deux which he later arranged for violin and piano. (Video courtesy of Classic FM)

The preceding piece by Kevin Malone (an American composer resident in Manchester) is an interesting one, because the title of the album is Violin Conversations and Kevin’s piece was very much about not being able to have a conversation…It depicts a situation which we all know too well: when you’re on hold on the phone and being told you’re ‘currently No. 27 in the queue’, but you never actually get through to a human being! The violin part sounds a little like Stravinsky’s L’histoire du Soldat, when the violinist becomes more and more frustrated…

Joseph Horovitz’s piece is quite programmatic, and there’s a lovely story behind that one. I got to know Joseph in my first year at the Royal College of Music, where he was the most brilliant lecturer. Not long after graduation I gave a recital at the lovely Leighton House, and Joseph presented me with this unpublished manuscript signed ‘Encore Piece! Best wishes, Joseph’. It was a solo violin piece based on the closing credits for the music that he’d written for the TV play The Dybbuk, so it’s called Dybbuk Melody. It’s so evocative, with a lot of Jewish elements: a bit like Bloch’s Nigun, which was the piece I’d played when I got a scholarship to the Royal College.

I was honoured earlier this year to give a concert at the Austrian Cultural Forum on the first anniversary of Joseph’s death, which included the piece that he would have saved above all others – the Fifth String Quartet, which was written for the Amadeus Quartet in 1969.

How much contact do you like to have with composers whilst they’re writing something for you?

It varies. Apart from Nigel Osborne, none of the composers here are violinists themselves, though like most composers many of them are fine pianists. Martin Butler sent me his Barcarolle out of the blue as a gift; he knew my playing quite well, and he said that he liked my ‘intense lyricism’ (which is true - I do love that aspect of the violin). It’s a sort of watery piece, marked ‘aquoso doloroso’, and at thirteen minutes it’s the longest work on the album.

When I went through the score Martin was very happy for me to ask questions and make suggestions if something didn’t quite work; I had a similar experience with Anthony Powers earlier in my career, where I was able to show him a more violinistic way of achieving the effect he wanted. It’s a very physical thing, the violin, because of the positioning of the fingers and string-crossings: sometimes passages just take a little while to work out, but sometimes a tiny adjustment makes a world of difference!

We've touched on several commissions which arose from friendships - but have any friendships arisen from discovering and performing existing works?

Yes, the inimitable Thea Musgrave is a case in point. I discovered Thea’s Colloquy many years ago, when I was looking for a piece of contemporary music for Park Lane Young Artists’ recital and went along to the National Sound Archive to get some ideas. I remember thinking it was a good piece, but I didn’t play it for years and years: it’s a tough piece from the 1960s, when she was going through a phase of writing serial music. What’s nice about this album is that it goes from something really popular with that piece from Howard’s The Snowman to something really hardcore from Thea: you need the grit in the oyster. It’s interesting that Douglas Knehans studied with her, but his piece Mist Waves is completely different – it’s really spacey and tonal.

I included Colloquy in my Century of Music by British Women concert, and that was when I realised there was no available recording - the one made by the dedicatees (Manoug Parikian and Lamar Crowson) was only ever issued on vinyl, so Ian Pace and I decided to do something about that. Once it was recorded and edited I thought I’d better send it to Thea, whom I didn’t actually know at that point: within 24 hours she wrote me a lovely email saying ‘This is fabulous – thank you for playing like angels, and do come and have lunch when you’re in New York!’

I happened to be in New York just a few weeks ago, and it was such a delight to meet up with her: she’s 95, bright as a button and absolutely wonderful company. She decided that when she turned 90 she was just going to write what she really wants to write, which sounds fair enough!

There are so many connections on this album that I didn’t know about when I started working on the programme: it turns out that Thea’s Colloquy was premiered in the same concert as the Rawsthorne Sonata, at the Cheltenham New Music Festival in 1960. Both of those pieces are really strong, so it must have been a terrific concert!

I gather that the recording of the Rawsthorne sonata was made much earlier than the rest of the programme…

Yes, my pianist for that one was the wonderful Andrew Ball, with whom I had a twenty-year duo partnership: we made four albums together, but it would have been nice to have recorded more. This is live recording of a concert we did as part of the BBC Millennium Series: the theme was originally meant to be music of the 1950s and we’d programmed Górecki, Petr Eben and Rawsthorne, but then the producer said we could mix things up a bit so we did the Ravel Sonata and the Brahms D minor as well – it was one hell of a programme!

It was also one of those lucky occasions where everything just comes together brilliantly, and it’s such a fond memory. Sadly Andrew developed Parkinson’s disease and couldn’t play for the last few years of his life, although he continued to teach – he died last year, so this is my tribute to a marvellous pianist and person.

Madeleine Mitchell (violin), Andrew Ball, Errollyn Wallen, Wendy Hiscocks, Nigel Clayton, Martin Butler, Kevin Malone, Howard Blake (piano)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC