Interview,

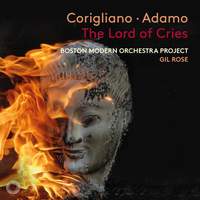

John Corigliano and Mark Adamo on The Lord of Cries

That opera turned out to be The Lord of Cries, a spine-tingling creepy fusion of Bram Stoker's Dracula and Euripides's The Bacchae on a libretto by John's husband Mark Adamo - himself a fine opera-composer, whose previous works include Little Women (1998), Lysistrata (2005), and The Gospel of Mary Magdalene (2013). It was a huge pleasure to meet the couple via video-call last month to explore the connections between these two seemingly disparate texts, how Mark managed to persuade John to reconsider his decision to never write another opera, and the pleasures of collaborating with one's spouse...

How did you hit on the idea of bringing these two texts together?

Mark: The Bacchae turned out to be the skeleton key that unlocked Dracula for me. Houston Grand Opera had invited me to adapt the novel, but I couldn’t find a reading that didn’t seem obsolete: after Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire, the idea of the vampire as a metaphor for sexual difference felt like a played card, and to me it doesn’t seem to be a metaphor for sexuality per se as much as for one’s animal nature.

I didn’t find any of the later adaptations particularly fresh, but two things occurred to me upon re-reading the novel. The first was that the vampire is a plot-point rather than the main character: you might as well make an opera about a great white shark as make an opera about Dracula, because there’s no internal development.

And the other thing was that the women were generally much more level-headed than the men: Harker and Seward and Van Helsing are always falling into each other’s arms, swearing eternal fealty and weeping hysterically…take a breath, guys! In most adaptations the focus is really on either the vampire or Lucy and Mina, and the men are essentially supporting characters.

I remember the late Bill Hoffman (the librettist for The Ghosts of Versailles) asking me how the adaptation was going and my honest answer was ‘Not well!’: I explained how I was struggling to get a handle on the story, and when I mentioned those specific elements Bill said ‘What you’re writing is The Bacchae!’. That was news to me! I went through a heavy Greek drama phase as a kid, but somehow I’d never got to this major play.

When I read through The Bacchae I realised that it’s the same story as Dracula: you’ve got this violently disordered, divine presence coming into the city from the East; you’ve got a spiritual leader who is secretly drawn towards what the god represents but cannot admit it; you’ve got the god who asks three times to be acknowledged and then wreaks a terrible revenge.

It’s chilling, actually, how all of these things stack up: Stoker read Classics at Oxford, so you have to wonder if The Bacchae had got into his imagination. The difference between The Bacchae and Dracula is that the Stoker gives us a falsely happy ending - much as Nahum Tate does in his version of King Lear, in which Lear becomes sane and is reunited with the family. Essentially Dracula is the Nahum Tate Bacchae: we drive a stake through the vampire’s heart and we all go home!

Tell me a little about the process of adapting Stoker’s narrative and characters…

Mark: All I needed to do was to map the play onto the novel and eliminate everything that didn’t fit into the Euripidean template. Seward would become the protagonist; Mina and Lucy could profitably be combined into one character, and Dracula becomes Dionysus. It seemed completely obvious to me, but when I presented it to Houston Grand Opera they said ‘Yeah…maybe not!’.

So I put it in a drawer and moved onto another project, The Gospel of Mary Magdalene, but a little later John and I were looking for something to do together and I suggested he should look at Dracula. The night before I sent the treatment off to Houston I remember saying to him: ‘I love what I’ve found in this dramatically, but if it’s accepted I’m going to have to bend over backwards not to write a good pastiche of your music – the scenario has your name all over it!’.

At that point John was insisting that he’d never do another opera - after every project he says ‘I’m never doing this again!’, so the fact that this is his second opera is kind of a record! It’s the first big thing we’ve done together.

John, what sort of sonorities leapt to mind when you started thinking about creating a sound-world for these characters?

John: Dionysus was the only role written for a specific singer – he’s this Other creature who’s neither male nor female, and writing for a countertenor completely solves that problem. I knew Anthony’s voice very well and have wanted to write for him for a long time: when he was about thirteen he sang my setting of Fern Hill for alto, chorus and orchestra, and I’ve followed his career ever since.

I immersed myself in the characters as deeply as possible, and that told me what their music should be. I wrote Seward for a very dramatic high baritone, although at that point I didn’t know Jarrett Ott’s wonderful voice. As Mark says, Seward is the protagonist in this, and he is fundamentally ill-equipped to make real decisions: his moral sensor button goes off, and he can’t display or even acknowledge his feelings. So I used the sonority of church bells as an orchestral colour for him – there is a way that you can make an orchestra actually sound like bells, and that’s Seward’s sound-world. The sound-world is completely different from The Ghosts of Versailles, just as my three symphonies are all scored differently.

Jonathan Harker is insane in this version, so I had to conjure the music of a madman; I found that if I had a small cluster of sounds undulating back and forth with pointillistic woodwinds above, then I could create the kind of music that follows him throughout. David Portillo actually had coaching with a drama-teacher to teach him to do all these wonderful bloodcurdling things: giggles, sobs, things like that.

The Bacchae chord actually came out of the name ‘Bacchae’, just like the BACH chord: I added A and E to get something which stacked up and made a great sonority which I was able to use throughout the piece. And Dionysus himself, when he speaks, is surrounded by radiant E major, with that halo of godlike purity – the orchestral writing is completely tonal, but he sings against it in other keys.

Mark: It’s like Lohengrin, but with one single, chilling displacement!

The stratospheric writing for the Three Sisters is extraordinary…

John: The first soprano is the one who goes stratospherically high, then there’s a regular soprano and alto: they’re the Furies, so they have to sound otherworldly. Our top soprano did an incredible job of hitting those super-high notes softly. It’s all possible – Tom Adès did this kind of writing in his operas, but he stays up there whereas I come back down.

Mark: I can say this and you can’t, but it’s also about the incredible harmony – I love the writing for those women! And because the two lower voices are in a normal human range they can carry more of the diction if there are moments when our high soprano needs to sacrifice just a little for the pitch.

I must also mention our wonderful Lucy, Kathryn Henry: a Young Artist who stepped in at short notice and covered herself in glory. Something similar happened when The Ghosts of Versailles went to Paris a couple of years ago, and Teresa Perrotta (who was scheduled to make her professional debut as one of the Gossips) jumped in to sing Marie Antoinette with so much poise that you’d never have guessed she wasn’t a seasoned artist. So there’s this club of soprano covers-turned-leads who leave the opera without their heads. John, you cannot behead any more sopranos - it’s become a trope!

I actually can’t think of another opera created by a married couple! Was your process very different from projects you’ve both worked on with other people?

Mark: The great thrill of coming back to my outline with John on board was that because I knew his work so well I could write the libretto on him, in the way that as a composer you write a role on a singer that you know. We both are rather organised thinkers who like to map out the structure of a piece before we finish the material, so when I gave him the first draft I said: ‘Here are the themes that I think can be revisited and transformed and here are some other things that you can take or leave, but we should probably agree on the underlying motivic structures’.

John, I think you pointed out that Seward’s three denials of Dionysus are a big signal-point in the original tragedy, and I’d kind of elided them. You suggested we have three big punctuated gestures to make that narrative quite clear, and that led to the Sisters’ wonderful trio ‘How many towers must topple’. The other point was the opening of Act Two: the first Act ends with this huge bacchanale and we had originally started the second with Seward coming on stage, but John said ‘We’ve just ended with all hell breaking loose. Can we open the second act with something eerie and calm to take the temperature down?’.

The Rape of Lucretia, The Turn of the Screw and The Rake’s Progress kept popping into my mind as I listened…did you look to any twentieth-century operas as inspiration?

Mark: We did have the prologue to The Turn of the Screw in mind, specifically for Anthony.

John: I love Britten’s operas and I know The Rake’s Progress, but I hadn’t made that association. Peter Maxwell Davies’s Eight Songs for a Mad King was in my mind’s ear, especially when I was writing Harker’s madness and the music for the Furies: surreal, out-of-the-ordinary vocal things which take singers to their limits.

Are there any plans for publication of the score, or for further performances?

John: It’s available on demand from Schirmer, and we’re probably going to excerpt certain arias to be formally published. The process was quite difficult for me because I tend to write in short score, which isn’t very piano-friendly - especially with these sliding clusters of sounds that go through microtones and various other unpianistic things. So I made the reduction for piano and synthethiser, but sadly most opera-companies don’t go for that. They did it on two pianos and they couldn’t sustain things – I don’t want a tremolo, I just want the same sonority! Take that E major writing for Dionysus: a tremolo there gives the wrong information about the character. We had the same trouble with Ghosts, which went through three different versions to make it playable on piano for rehearsal.

We were very fortunate that Gil Rose who runs Boston Modern Opera Project brought the original cast to Boston for a concert-performance and then recorded. Opera recordings are usually taken from live performances these days, but we had actual sessions. That was great because the singers had already performed the piece and it was really a part of them.

Mark: The good news is that we’re living through a golden age of contemporary opera - when John wrote Ghosts it was the first time the Met had commissioned anything in 35 years, and now they’re doing new music all the time. In my own composing career Little Women has travelled everywhere: it’s never off the stage, but things are harder now. It’s difficult to find co-productions or second performances because everyone is doing premieres!

Anthony Roth Costanza (Dionysus), David Portillo (Jonathan Harker), Jarrett Ott (John Seward), Kathryn Henry (Lucy Harker), Matt Boehler (Van Helsing)

Boston Modern Orchestra Project, Gil Rose

Available Formats: 2 SACDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC