Interview,

Raphaël Pichon on Monteverdi's Vespers

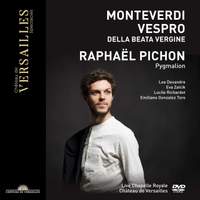

Back in September, Raphaël Pichon's new recording of Monteverdi's Vespers made a huge impression on me and my Presto colleagues; it's quite possibly the new benchmark against which recordings of this unique masterpiece should be measured. Not for nothing did it also finish in our Top 10 Recordings of the Year for 2023!

Not surprisingly, when the opportunity to talk to Raphaël about his relationship with this music arose, I jumped at it - I was curious to know where he'd got the idea of including the closing blessing, re-using the opening music, as well as to dive into other historical aspects of the music. Along the way, Raphaël also explained some of his thinking about other areas of repertoire, seeing through-lines across the centuries of French opera and across the years of Mozart's short life - connecting his childhood to late works like the Requiem in ways that aren't often realised.

There's nothing more exciting than to record a piece where you feel you have had a real journey with it. It's something really special. And of course it's also a really special piece for us - all the Pygmalion forces. For me, it was one of the crucial pieces that changed my life when I was a teenager. I had the chance to sing it when I was about ten or eleven, and many times after that, and it's the kind of piece where you feel transformed after the performance. It's absolutely unique. And on the way we've done a lot of different versions - concert versions, spatialised versions, and staged versions. We produced a full stage performance in an old oil factory in Amsterdam with Pierre Audi for the Holland Festival.

We've had the chance to experiment with many different combinations, instrumentations - it's a really detailed work, but even within that there is still a huge space for freedom and experimentation. Sound experimentation, spiritual experimentation. And I'm really happy that we had that background before recording it; I've changed my mind many times, and of course we could do another recording next week and that would be totally different again.

The main thing for me is the choral aspect of the piece.

How much difference do singers’ vocal personalities make when putting together a work like this? Do you “cast” the soloists in the same sort of way you would cast operatic characters, looking for certain qualities?

Of course. First of all because - especially for the male voices - it's asking for very virtuosic singers. Really intense, special abilities; look at the tenor voices in the Gloria Patri at the end of the Magnificat, or Duo seraphim. And also for the basses, because when you choose to perform it in the original key it's quite demanding and quite high. So it's creating something really dramatic, and you feel the effort and the sense of surpassing oneself. For me, that's a really key part of the piece, of the odyssey that it represents.

So yes, that's something I keep in mind, and also the contrasts and the colours - for instance the contrast between these two tenors. They need to be able to really sing together but also to create quite different personalities in the two long tenor solos. Between Nigra sum and Audi coelum. It's a combination of artistic and vocal personalities, drama, colours - and also the special requirement in this music of using the gorgia technique for the ornaments, which is really difficult. It's a challenge that I love.

Several movements - perhaps above all Audi coelum, with its clever textual use of echoes - hint at a Gabrieli-esque use of spatially-separated musicians as a device within the music. Was this still in vogue in Monteverdi’s time?

Oh, yes. In each psalm Monteverdi is using different combinations, different spaces. He's opening up a different world, a different galaxy. I think it's really a "space odyssey" in a sense! He's using so many different languages; of course it's a piece that uses immemorial languages that come from various roots in the past, in ways that it's sometimes impossible to tell. Sometimes you have the sensation that it's enriched by the Mediterranean culture; you feel like you might be listening to a muezzin at times.

Looking at the future and the seconda pratica language, opening up to the opera world, it's like an epiphany - or perhaps more like a pentecostal experience. Speaking all the languages of the world.

Many times over the centuries, church authorities have reacted against sacred music that was too “theatrical”. Is there any indication of this having been true of the Vespers in Monteverdi’s time?

No - because at this point the Counter-Reformation was a really important development for music. There was an acceptance of the fact that they needed to use direct language as much as they could. The pure world of harmony and the perfect harmony of the Renaissance was gone - now the need was for the listener to hear and clearly understand the text. So to use operatic approaches was absolutely permissible.

The closing blessing at the end, re-using material from the opening to bring the music full circle, is an innovative touch. What led you to incorporate this element into the recording?

There's still a discussion in respect of the Vespers (maybe not a particularly interesting one...!) about whether it's a collection or an entire piece. The genius of it is that for me at least, it's clearly both. It means that of course you could pick out one psalm or another and it would work by itself, but if you experience the full journey, it's something unique.

If you consider the whole work, you start with that first call but you're missing what would normally be the final blessing, Benedicam Domino, which normally closes the office or service of Vespers. That's why I started thinking: OK, if Monteverdi had to conclude this piece, what would be the right music to use? And it became clear that it's a circular piece - continuing with that allegory of the cosmos, we're going back to the start. I was really surprised that the meter of these final words fitted perfectly with the falsobordone of the opening movement.

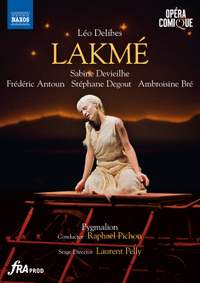

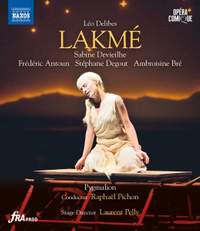

Pygmalion’s next release, a DVD and Blu-ray of Delibes’s opera Lakmé, seems quite different from most of your recordings to date; are there hidden similarities between this and earlier French operas that you've recorded?

Yes, there are a few. It's not exactly similarities, more a question of legacy and heritage. Of course there's this transparency, and the kind of declamation where the music follows absolutely and clearly the rhythm of the text, which comes from the French récit of Lully and through Rameau. There's a lot of that in Lakmé. And this ability to create a pure suspension and really deep drama. It was an adventure; we had to face many new parameters, in terms of the instruments for example. These French instruments from the late nineteenth century, which was quite a new experience especially for the wind players, with different fingerings and different kinds of sound, but it was a unique adventure.

I'm hoping it will be just the start of a French adventure in the future; we will continue in this repertoire in the coming years.

You've also just recorded a new Mozart Requiem, which includes much earlier works by the young Mozart interspersed between the movements. Can you tell us a little more about this project?

It's a great project; we developed this for a staged performance of the Mozart Requiem, which we created in 2019 in Aix-en-Provence with Romeo Castellucci as stage director. We've since revived it a lot - in Brussels, Vienna, Naples - and it felt like the time to record it. It's really about memory; I was really shocked when I discovered one of the first motets Mozart ever wrote, as an exercise for his teacher Padre Martini, which is in D minor that is exactly like the opening of the Requiem. The same harmonic journey. This discovery really made an impression on me; everything had been there from the start.

Of course, with the Requiem there are so many questions about versions and whether you complete it; so I decided to interpolate these other pieces to create a kind of box of memories, or a dialogue, where we're inserting other things. An exercise written for his wife, a memory of the Gran Partita or of the incidental music to Thamos, King of Egypt... and so it's a really nice kind of dialogue between the Requiem and different pieces from the past.

We just recorded it last week, and it'll be released next year.

Pygmalion, Raphaël Pichon

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Pygmalion, Raphaël Pichon

Available Format: DVD Video

Sabine Devieilhe (Lakmé), Frederic Antoun (Gérald), Stephane Degout (Frédéric), Ambroisine Bré (Mallika), Pygmalion, Raphaël Pichon, Laurent Pelly

Available Format: DVD Video

Sabine Devieilhe (Lakmé), Frederic Antoun (Gérald), Stephane Degout (Frédéric), Ambroisine Bré (Mallika), Pygmalion, Raphaël Pichon, Laurent Pelly

Available Format: Blu-ray