Interview,

Christophe Rousset on Lully's Atys

Few musicians in the recording era have done more to fly the flag for Jean-Baptiste Lully than Christophe Rousset: it was back in 2001 that the French harpsichordist and conductor embarked on his mission to record all of the composer's operas with his ensemble Les Talens Lyriques, and the fruits of his labours to date have seen him described as 'indisputably the outstanding Lully conductor of our day' (Opera Magazine) and 'a state-of-the-art Lulliste' (The Sunday Times).

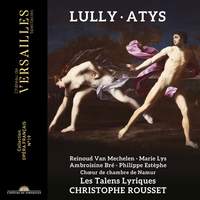

As the series nears the finishing-line with a typically outstanding account of 'the King's opera' Atys (starring Belgian tenor Reinoud van Mechelen in the taxing title-role), Christophe spoke to me from his home in Paris about how this son of an impoverished Florentine miller rose from dancing for his supper in the streets to cutting a swathe through the court of Louis XIV - and the uncanny magic of recording this music at Versailles, where it all began...

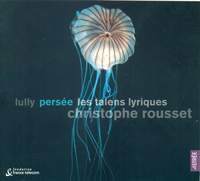

You began your survey of Lully's complete operas over two decades ago, with Persée - when did you first fall under the composer's spell?

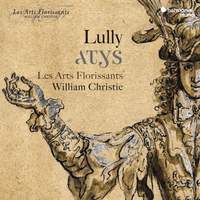

I didn’t know much at all about Lully until I started working as assistant to Les Arts Florissants and William Christie in the 1980s. We did a production of Atys in 1986, and I really fell in love with this music: it’s so flexible and sensitive, and somehow it manages to be simple yet sophisticated at the same time. And I had this flash of inspiration when I realised that the same way of doing the recitatives in Lully could also be applied to Gluck…It took me quite a while to come back to Gluck, but when I started conducting his operas I managed to do exactly the same: to be as flexible but as faithful to the language as possible.

Lully started writing operas in the 1670s, and if you look at the map of Europe at that time you see that nobody else was doing anything that was really comparable in terms of scale or complexity. If you look to Italy – to Rome, to Venice, to Naples – you never find that kind of architecture and variety. With Lully, you have orchestral pieces, dances, arias, recitatives and all sorts of machinery: it’s a really big thing!

In France for many years people compared Lully unfavourably to Rameau, arguing that Rameau is much richer, more surprising, more inventive and so on…But those people forget that there are sixty years between them, and that’s a long time in music history: it’s like comparing Carmen to Stockhausen! Lully’s operas were still being performed in Paris during Rameau’s lifetime, but when Lully created his works there was simply nobody else to touch him: he was very much the triumphant hero himself.

Atys was known as 'l'opéra du Roy' because of Louis XIV's great enthusiasm for the piece - why do you think this particular score was such a favourite?

Louis XIV loved Lully’s music, because it’s so rich and appealing. Obviously he wanted the operas to include a certain amount of propaganda, which is why so many heroes in Lully’s operas are kings or sons of kings. Atys opens with a prologue singing the praises of ‘le plus grand des héros’ [‘the greatest of heroes’]: that’s very clearly an address to Louis XIV!

But despite all the grandeur and goddesses, the opera tells a very human story: two young people love one another but daren’t confess that love…and when they do, it gets problematic! It’s about young love, suffering in love, the desire for vengeance and how far you’re prepared to take that desire…these are emotions which everyone still can feel today, and I think that aspect is what really touches you in this piece.

And what are the highlights of the score for you personally?

There's a very clear structure, and that’s what I love most of all about Lully’s operas – the architecture. As in Classical French tragédie you have tension growing until the third act, which is the turning-point…and then the catastrophe comes. The pivot is actually the sommeil, the sleeping-scene, which is just magic: it’s so beautiful and unforgettable and powerful. The music evokes Atys’s dream so well that you can’t resist entering that world, then afterwards it’s just one disaster after another! It all culminates in the revenge of the goddess Cybèle, the death of the princess Sangaride and the suicide of the young Atys - so the opera ends in a very dark way, with a big funeral oration.

Despite spending most of his life in Paris, Lully was born in Florence - do you hear any Italian accents in his operas, or did he leave his native country before he could really absorb many influences?

He travelled from a very young age, and in Italy he was mostly a dancer - that never entirely left him, and in fact he went on to dance with Louis XIV in his ballets! Lully was only a teenager when La Grande Mademoiselle [Anne Marie Louise d'Orléans, Louis XIV’s cousin] brought him with her to Paris, so he received most of his education in France. Because he was so young and moving in such elevated circles, he really absorbed the French style, rhetoric and language: he sets French verse so naturally, with the fluency of a native speaker.

I’m sure that anyone who’s spent time around Italian people knows just how charming they can be, and I sense Lully had this personality! His charisma may have been a bit fake at times, but it was certainly effective: he was a notorious tyrant with his musicians and thought nothing of breaking a violin or jumping into a harpsichord, but with the king and other important people he could turn on the charm to obtain exactly what he wanted.

The arts were so important in France during this period, so he was a very influential figure with a lot of status: this was someone who could interrupt the king when he was in conference with his ministers! Lully was an incredible arriviste: this son of a Florentine miller ended up rich, famous and ennobled, with various lavish houses in and around Paris. His music was published and performed all over France and even abroad: it’s very clear that Purcell, for instance, knew his work.

Tell me a little about the relationship between Lully and Philippe Quinault, who supplied the libretto for Atys and several subsequent operas...

It was a very special collaboration. Lully was a despot who knew exactly what he wanted, and I get the impression that Quinault was probably a very flexible and kind person – he would propose a libretto and Lully would change what he thought was too weak or not exactly as dramatic as required. And sometimes it really was a case of prima la musica, e poi le parole: for the dances and sung dances, Lully would compose the music for the dancers first and Quinault would add the verses afterwards.

These Lully/Quinault collaborations are full of aphorisms, where things start to be very philosophical and detached from the action: some figure in the opera will think ‘Love is always like this…’ and develop that idea in really clever directions. The thinking is very clear and seductive, and the language is so beautiful – it’s not quite as rich as Racine or Corneille, but it’s at a very high level and also very related to the spirit of the age. (When I conducted Gluck’s Armide on the same libretto by Quinault, I felt a real clash between the emphatically seventeenth-century text and the obviously eighteenth-century score: Quinault’s libretto is very much Grand Siècle).

And it’s clear from testimonies of the time that the libretto had a very strong impact on audiences: Madame de Sévigné writes that after attending a performance of Atys, she and her friends would declaim just the libretto (without music) because they found it so touching in its own right.

The title-role (written for haute-contre) is an enormously taxing assignment, both vocally and dramatically - when did you identify Reinoud van Mechelen as the man for the job?

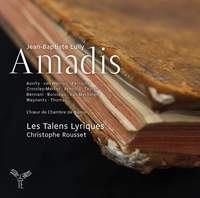

The first time I recorded with Reinoud was when we did Amadis about ten years ago: he was singing just the passacaglia at the end of the opera, and I thought ‘Oh my god, what a voice!’. I’m so happy to have him for Atys, because he’s really at the peak of his artistry: he knows so much about this period and uses his voice in such a way that you have exactly the right colour and expression, which is quite rare. The French haute-contre repertoire is a very difficult, specific matter, and he’s just outstanding in every respect.

I gather you made this recording at Versailles, where the opera was premiered: does being 'on location' add another dimension to a project like this, either in terms of acoustics or simply atmosphere?

We recorded it in the theatre, and finished all the recitatives in another room in Versailles. It’s an absolute privilege for us to record this music with the right aesthetics and surroundings. I don't know if it helps in terms of acoustics, but just being there is inspiring - the spirits of Louis XIV and Lully are somehow around! And I think that's actually what the king intended: he wanted to stake his place in history with this big monument, and Lully’s music is an integral part of that.

How many Lully operas do you have left to record now?

We still have Proserpine and Cadmus et Hermione to go, then we’ve done the lot! The very first one was Persée, and I still love it. I kept Atys for the final few, partly because I wanted to leave enough time to forget what we did with Les Arts Florissants back in the 80s: I was very much an active participant on that recording, and I was keen to come to the piece afresh. And it’s been nice to revisit it with all this experience of conducting ten other Lully operas under my belt: I feel like I have built something specific in my head and my soul now, and this Atys is somehow the culmination of all that.

Last time we spoke, you were just about to go into the studio with Michael Spyres to record a programme exploring Wagner and the composers who influenced him...how did it go, and do we have long to wait?!

It’s recorded and edited, so in March we will have the real Wagner revealed, on original instruments with a great tenor. Michael is just incredible – I always enjoy every single note with him. As well as Wagner himself, we have Rossini, Marschner, Beethoven…so many incredible composers, and he does all this repertoire in the most splendid way. He has not only an extraordinary vocal range but also so many colours in the voice, and is such a lovely person: always very ready to do whatever you want as a conductor, always willing to ask for help!

He’s so inspiring to work with, and I can tell you that every single musician in my orchestra was so keen to be part of that wonderful project. It was quite an experience: tell me what you think when it comes out!

You can browse all of the recordings in Christophe Rousset's Lully series here.

Reinoud Van Mechelen (Atys), Marie Lys (Sangaride/Flore), Ambroisine Bré (Cybèle), Philippe Estèphe (Célénus)

Les Talens Lyriques, Choeur de Chambre de Namur, Christophe Rousset

Available Formats: 3 CDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Guy de Mey (Atys), Agnès Mellon (Sangaride), Guillemette Laurens (Cybèle), Jean-François Gardeil (Célénus)

Les Arts Florissants, William Christie (assisted by Christophe Rousset)

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC

Cyril Auvity (Amadis), Judith van Wanroij (Oriane), Edwin Crossley-Mercer (Arcalaüs), Ingrid Perruche (Arcabonne), Benoît Arnould (Florestan), Bénédicte Tauran (Urgande), Reinoud Van Mechelen (Un captif/Un berger/Un héros)

Les Talens Lyriques, Chœur de Chambre de Namur, Christophe Rousset

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Paul Agnew (Persée), Anna Maria Panzarella (Andromède), Salomé Haller (Mérope), Jérôme Correas (Phinée)

Les Talens Lyriques, Chantres de la Chapelle, Christophe Rousset

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC

Due for release on 1st March.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC