Interview,

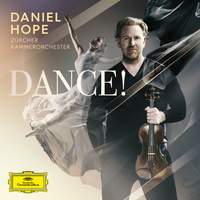

Daniel Hope on Dance!

I spoke to Daniel shortly after the album's launch at Yellow Lounge in Berlin last month about the project's long gestation, the social and political motivations behind 'people's need to move to music' over the centuries, some of the discoveries and musical friendships which he made along the way, and why he 'dances best when no-one's looking'...

I gather this project has been in the pipeline for some time...when and how was the seed planted?

It’s been in the works for twenty years: this was one of the very first ideas for a concept-album I had, at a time when concept-albums weren’t really getting any sort of acceptance. I’d long been fascinated by the stories behind why people have felt the need to move to music through the ages - whether it was for medicinal purposes, whether it was because society or the court expected them to do so, or whether it was just down to the fact that music took a hold of them.

When I started off it encompassed 500 years of dance music; when I came back to the idea two decades later, 500 became 700! In the course of that time I’ve naturally changed and grown: I’ve met so many different musicians and performed so many different musical styles, so the original concept had evolved into something much more diverse and varied in terms of the repertoire and the performers involved.

The project could have developed in so many different ways: you could record twenty CDs of dance music and still barely scratch the surface! But I decided to start with the beginning of notation, because at some point somebody must’ve decided that dance music was so important that they needed to reach people by putting it down on paper, even if it was in a basic form. And taking in those extra 200 years really makes a difference - the music of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries is a whole different ball-game from Renaissance and Baroque.

With so much material potentially at your disposal, how did you go about curating such a coherent, compelling programme?

I kept an open mind, gathering as much information as I could and whittling it down at the very end! You could easily do an entire album of waltzes or tangos or polkas, but I wanted to show as many musical styles and rhythms as possible: time-signatures play such a crucial role in defining how we dance and move and feel. We all know that the waltz is in 3/4 and the gavotte is in 2/4, but if we venture beyond duple and triple time and start looking at 5s, 7s and 9s then we’re in the territory of folk music - and Balkan and Indian music in particular make such interesting use of those meters.

The next step was to look into the geographical and political reasoning behind how dance changed and what it meant to different groups of people. When I mentioned ‘medicinal purposes’ earlier, I was thinking of the danse macabre idea of using dance to ward off evil spirits, but you also see dance being used to pray for rain, to mark key moments in the life of a family or community…to define one’s entire life, basically!

As the project started to gather pace, I got into the fascinating subject of colonialism - particularly in the case of the Spanish and Portuguese, who took their musical forms to the New World and enforced them on the inhabitants. Colonisers enslaved indigenous people who then reacted to the way in which they were forced to dance and move, then those people brought their own expression into the music, which then filtered back into Europe in the late Middle Ages and early Baroque period. Eventually people like Mozart and Schubert picked that up, and it changed again…

How much of a challenge was it to track down editions of that music from the late Middle Ages?

So much material has been made available online over the past few years – it’s still a challenge, but it’s findable. I had several people helping with that, but I must give a shout-out to the extraordinary Olivier Fourés: in addition to being a great researcher and musicologist he’s also a dancer, so he was a wonderful go-to person in terms of repertoire suggestions. He’ll send me things that are totally unrelated to upcoming concerts or recordings, just to go into the ideas box I’ve had for decades; they sit there gestating until one day I think ‘That could be a full-time project!’

Tell me a little about some of the specific pieces you discovered along the way...

The fandango by Nicola Conforto was an eye-opener, because I had to rethink my whole knowledge of the genre (which admittedly wasn’t terribly well-informed to start with!). When I started to dig deeper into its history, I found that there was this whole sweep of fandangos that came from South America, Latin America, Cuba and enslaved communities: they took this dance and shot it straight back to Europe, where it caused a huge scandal. The fandango was banned by the Catholic church: it was seen as a disruptive force because it would inspire a man and a woman to get closer together, to move and gyrate and basically do everything you weren’t supposed to do!

I’d always thought of the fandango as a rather stately kind of thing, but it was nothing of the sort - it was raunchy and dangerous, and the puritanicals hated and feared it because they knew it could incite passion and destruction! Then people like Mozart and the European gentry picked it up and ran with it, diluting back into what I always thought it was.

I think the Dall’Abaco piece is another absolute gem: I knew his name but can’t say I knew his music very well before this project. I’ve discovered someone who is every bit as arresting and exciting as Vivaldi, and yet does it all with a tremendous elegance and grace. It’s a very singular piece that looks at the idea of dances and jigs, and has a brilliance to it which I absolutely love.

And a whole other realm of surprises happened once we got into the studio and dreamt things up on the spur of the moment. The Odessa Bulgar is a tune I’ve known and played for years; for the recording sessions we had Jenö Lisztes on hand, who is probably one of the great cimbalom players on earth, and he asked if he could join in. We hadn’t planned on putting a cimbalom into the klezmer music but I thought we should give it a try…The moment you hear the cimbalom you start to totally rethink what that music means: what is klezmer, and where does it sit within the Central European tradition?

It’s like when you hear a Brahms Hungarian Dance done with a cimbalom and a bass player rather than a symphony orchestra, and it makes you wonder about where he found those themes in the first place. We know that he loved listening to gypsy musicians playing in Viennese cafes, so he may have heard something there which inspired him to go on and write some of the greatest dances in history.

Florence Price's 'Ticklin' Toes' was a new work to me, and an absolute delight! Where does she fit into the story?

I’ve been really into Florence Price for the last three or four years: I recorded Adoration on my America album in 2022, and this time around I was looking for something that alluded to ragtime, which I think is still very underestimated as a genre. People recognise the genius of Scott Joplin, but beyond that it’s often seen as a sort of placeholder that was briefly in vogue at the turn of the century, before jazz really came along… I’m not of that opinion: I think that ragtime was tremendously important and influential in amplifying the music of African-Americans at a time when they had very little chance to express anything. These composers weren’t just treading water before the jazz age: they were real pioneers.

Price is not a ragtime composer as such, but she uses ragtime in that piece so it became a crucial chapter in the story I wanted to tell: I knew I was heading towards jazz and Duke Ellington, but I was keen to show some of the gestation of that music. It goes back to back to the spirituals and protest songs of the African-Americans, which is fundamentally important to jazz and to the music of America as a whole. The Americans have contributed so much to the history of dance music, especially if you think of the turn of the century and the advent of foxtrot and swing in the 1920s – all of that came primarily from the United States, and African-Americans played a huge part in that.

How did people respond to the programme you played at Yellow Lounge in Berlin last month? Did the audience literally accept your 'invitation to the dance?

Yellow Lounge is quite a short set, usually only about twenty minutes: we had a klezmer piece, a tango and waltz, and right from the start people started to move. Since concert-halls reopened after the lockdowns, the energy has somehow shifted: you have the feeling that people want to be there more than ever, that they really relish the chance to experience live music and react to it in the moment.

When I was on tour with the American album right after things had opened back up, we played some Gershwin and Duke Ellington and people were getting up and dancing in the aisles! I’d never experienced that in a classical concert, but suddenly it was happening every single night; there was something infectious and wonderful about it, and that was one of the reasons I thought it was maybe the time to try this album. I can’t wait to go on tour with it, and try and generate some of that positive energy which I think we all need right now on our very troubled planet…

Over the past year or so, we've spoken to musicians who dance to near-professional standards and others who insist they have two left feet - where do you fall on that spectrum?!

When I hear music I just can’t sit still, but I would not describe myself as a good dancer. I dance badly, but extremely enthusiastically – I’m at my best when no-one’s looking! And that’s OK: I don’t think you have to be good at it in order to enjoy dance and music. Just let the music grab hold of you and take it from there!

Daniel Hope (violin), Zürcher Kammerorchester

Benjamin Günst (violin), Jenö Lisztes (cimbalom), Omar Massa (bandoneon), Stephane Logerot (bass), Joscho Stephan (guitar), Jacques Ammon (piano), Marie-Pierre Langlamet (harp)

Available Formats: 2 CDs, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC