Interview,

Kirill Gerstein on Scriabin

Pianist Kirill Gerstein recently joined Vasily Petrenko and the Oslo Philharmonic for a double-bill of Scriabin - the richly Romantic Symphony No. 2 and the unique Piano Concerto. The latter is, perhaps surprisingly, Scriabin's only foray into this genre, and has tended to languish in relative obscurity.

Pianist Kirill Gerstein recently joined Vasily Petrenko and the Oslo Philharmonic for a double-bill of Scriabin - the richly Romantic Symphony No. 2 and the unique Piano Concerto. The latter is, perhaps surprisingly, Scriabin's only foray into this genre, and has tended to languish in relative obscurity.

I spoke to Kirill about Scriabin's often mysterious, always fascinating music, and how the Piano Concerto fits into the development of his compositional style.

Much has been written about Scriabin’s interest in the mystical and in esoteric philosophy, and this influence is certainly plain in his later orchestral works. Do you think there already hints of this in the concerto, written when he was just 24?

Obviously given that we know what happened later, it’s easier to trace, but yes – I think it’s fair to say that in the concerto you start to hear it. It’s still very far from the ecstasy and the mysticism of the later works (and these are not really that much later – ten or fifteen years). There’s a certain nervousness and a certain hint of that ecstatic reaching towards the sky in the concerto, particularly in the third movement, with the second theme that comes twice and then returns triumphantly at the end. The way that sounds, to me, suggests it’s already got the same DNA as the later works and some of the same things are beginning to unfold.

Why do you think this concerto, which is surely every bit as powerful and expressive as those of other Russian Romantics, has never quite made it into the mainstream of the repertoire to the same extent?

I think one of the reasons is that it’s a youthful work, and such works don’t always fare so well. Because of this, it doesn’t hold together as well and as safely as later pieces like Rachmaninov’s Third Concerto – difficult as it is, if everybody knows what they’re supposed to do, the piece emerges. I think with the Scriabin, you need to rehearse it quite a bit, and the orchestra needs to have this feeling of rubato and freedom, which the conductor too has to feel and has to be on the same page as the soloist. So it’s a very co-dependent piece, and in some ways it’s more fragile.

The same thing goes for balance, because in the piano concerto he’s not yet as experienced in orchestration as he was later – and again, I don’t think that means that the thing doesn’t work so well, but it’s more fragile and it needs more care for it to work. As a consequence, it’s not a work that you can just decide to throw together on one rehearsal because ‘everyone knows how it goes’!

Scriabin, like Rimsky-Korsakov and others, took an interest in the relationship between the senses, hearing “colours” associated with keys in a way that seems to suggest synaesthesia but yet also often end up being very subjective and personal. Do you think that thinking in terms of these colour-relationships might offer insights into the moods and shades in Scriabin’s music?

It is illuminating (no pun intended) – in terms of the information we can get. It’s more relevant for some of his other works, like Prometheus (which is our next release); when we performed this in a concert in Oslo we actually had realisation of the lights. It’s interesting you should ask this, particularly in relation to Scriabin, because on the one hand it does appear that he was experiencing synaesthesia, but equally when one looks at involuntary synaesthesia as described by neurologists it’s not exactly the same as what Scriabin had. He did think about it quite a lot and there are certain signs that point to his having also studied the spectrum of light, and so on. So it wasn’t just instinctive and involuntary.

As for whether it’s helpful when studying the music… In his later works it does seem that his colouring of elements of the music – the bass is this colour, and this other motif is that colour – and it does end up providing a certain insight into how he sees the harmony of a particular moment in the piece. With the chords that we find in his later work, which are so ambiguous, from the perspective of traditional analysis maybe one could say it’s a chord based on F sharp with added notes and inversions, but at the same time you could see it as being based on C with these extra notes and inversions… from the music-theoretical point of view it’s unclear, but if you look at which colour he marks for that chord then you actually see which harmony he meant, and how that harmony appeared to him. I think it is of use and it is informative; at the same time it’s important to note that the music is strong enough on its own. You could play a very good Prometheus without knowing the colour-scheme and the music works on the basis of sound-relationships too. It’s not an indispensable key to the music but it is an additional fragment of information.

Thomas Møller’s notes mention that Scriabin not only had small hands for a pianist (especially compared to Rachmaninov’s famous span!) but also injured himself while practising Liszt; some have speculated that these circumstances had a key impact on how Scriabin wrote for the instrument. Do you think there’s evidence of this in his piano writing (both in the concerto and elsewhere?)

He was writing for a very Chopin-esque hand. If there’s an inheritor on the piano of Chopin’s figurations it might be Scriabin – especially early Scriabin – whereas Rachmaninov is much more inheriting and continuing the Lisztian tradition. That’s quite rare, and I think the filigree and the spinning of the passagework is quite Chopin-esque. It’s true he has somewhat less broadly-spread chords than Rachmaninov, but equally with the ecstatic and nervous quality to his music, there is this sense of reaching for very wide intervals that obviously have to be broken on the keyboard, no matter what size hands you have. And this plugs in well into the idea of reaching for more than one can grasp under normal circumstances, so there are a lot of spread chords all the same. Perhaps, when the question is posed like that, you could say that it’s less robust piano writing, possibly dictated by a less robust physique than Rachmaninov’s, when one compares the two of them – but not as weak and as small as the clichés sometimes suggest about Scriabin. Yes, in some ways he was not a physically bulky or robust person, but there’s a lot of strength in his writing.

You’re clearly something of an advocate for Scriabin’s music in general – can you tell us a little about how you first encountered his work, and why you’re so fervent an evangelist for him?

The first time was when I was growing up in Russia – some of the Op.11 Preludes that I played around the age of about 10 or 11. It’s music that very much permeated the atmosphere even as I was growing up – certainly Rachmaninov but also Scriabin. I remember as a child going to the Scriabin Museum – his house, where he lived in Moscow. When you experience that, especially in the winter, in the snowy small streets of Moscow where this house is, it’s very moving. The old ladies let you play his Bechstein!

There is, then, a sentimental connection; in addition, my teacher Dmitri Bashkirov is a well-known exponent of Scriabin’s works and made a famous recording of the concerto with Kirill Kondrashin. Actually that was one of the pieces that I heard him play in my home town when I was about 6 or 7. Years went by and I started to study with him, and some more years went by and I thought I would like to study this piece with him because he was so associated with it. And some more years went by, and I played it in concert, and even more years went by, and I ended up recording it! So there is that long connection with the concerto in various ways.

Above all, it’s simply good music. It’s quite unique; there isn’t anything else that’s quite like Scriabin, so aside from my personal connections I feel it’s music that should be heard and played. It’s rewarding, both to play and to listen to, and obviously I’ve had a long exposure to it and it feels close to me.

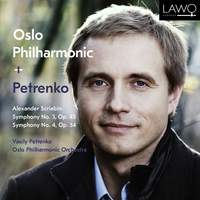

Scriabin: Symphony No. 2 & Piano Concerto

Kirill Gerstein (piano), Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Vasily Petrenko

Kirill Gerstein and Vasily Petrenko's Scriabin collaboration was released on October 13th on LAWO.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

'[Petrenko] shows an excellent grasp of each symphony's dramatic trajectory, and a broader than usual awareness of the creative legacy within which Scriabin worked.' (BBC Music Magazine)

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC

Gerstein plays works by Bach, Beethoven, Scriabin and Earl Wild.

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC