Interview,

Semyon Bychkov on Mahler

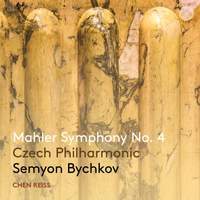

This coming Friday brings the first instalment of Semyon Bychkov's new Mahler cycle with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra on Pentatone, in the form of the Fourth Symphony with Chen Reiss (herself a recent Presto interviewee) as soprano soloist. In the lead-up to the release, Semyon spoke to me from his home in Biarritz ('my paradise!') about his first heady encounter with Mahler's music as a schoolboy in St. Petersburg, why he resisted conducting several of the symphonies for so long, the special significance of the composer's Bohemian roots, and his conviction that 'all Czech people are born musicians'...

This coming Friday brings the first instalment of Semyon Bychkov's new Mahler cycle with the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra on Pentatone, in the form of the Fourth Symphony with Chen Reiss (herself a recent Presto interviewee) as soprano soloist. In the lead-up to the release, Semyon spoke to me from his home in Biarritz ('my paradise!') about his first heady encounter with Mahler's music as a schoolboy in St. Petersburg, why he resisted conducting several of the symphonies for so long, the special significance of the composer's Bohemian roots, and his conviction that 'all Czech people are born musicians'...

How much contact did you have with Mahler’s music during your student years in the Soviet Union?

When I was growing up in St Petersburg (Leningrad at the time), Mahler was a fairly rare event. The conductor Nikolai Rabinovich, who was one of the professors at the Conservatory, was a passionate champion of Mahler, but otherwise it wasn’t performed very frequently at all. That wasn’t the case in Moscow, however: Kirill Kondrashin recorded the entire cycle (with the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra), as did Gennady Rozhdestvensky.

My own first encounter with Mahler was quite amusing: I was no more than thirteen at the time, and the short story is that his music made me accidentally skip class! From the age of seven to seventeen I studied at the Glinka Choir School, and the school building is connected to the Academic Glinka Capella - a little jewel of a concert-hall, with beautiful architecture and acoustics. What’s known today as the Leningrad Symphony Orchestra (essentially the second orchestra of the Philharmonic Society) often rehearsed in there, even though they usually played their concerts in the big Philharmonic Hall.

We had 45-minute classes with a 10-minute break, and during those breaks I would run like crazy to the concert-hall just to see what was going on. You enter the hall from backstage, so you find yourself right behind the orchestra; when I arrived there was absolute silence, then out of that silence something stirred into life and I was suddenly in the middle of the most unbelievable sound-world, like nothing I’d ever experienced before. I completely forgot about getting to my next lesson…

I had no idea what I’d just heard, but when school was over I was walking round the streets and saw a poster announcing a performance of Mahler’s Third Symphony and it all fell into place: I knew nothing at all about Mahler at that stage, but I later realised that what I’d stumbled into was the beginning of the finale, ‘What Love Tells Me’. By that age I already knew I wanted to conduct, and that’s how it all started: a lifetime of exploring and loving this music.

When did you first get a chance to conduct it yourself?

The very first opportunity came some years later – naturally I never conducted it in the Soviet Union, but when I was still at the Conservatory I brought the Fifth Symphony to my professor Ilya Musin. I was invited to make my debut with the Leningrad Philharmonic when I was still a student, and knowing my love of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony Musin suggested I propose that. My response was ‘Yes, the only problem there is that I still have no idea how to deal with the Scherzo!’. Ultimately I decided against programming it then, because if you don’t really have a conviction as to how you’d like to do a piece then there’s no point!

In 1979 I was invited to conduct in Michigan (my US professional debut), and for that I chose Mahler’s Fifth and Mozart’s Symphony No. 39 in E flat major. That was the first time I conducted Mahler in my life, and from then on he’s been an almost constant companion.

What had happened in the interim to make the pieces fall into place?

Good question! I think it simply comes down to living with the music – there’s just no substitute for that. Sometimes you simply don’t know what to do with a piece, and in that situation I think you should wait: I cancelled the Ninth Symphony four times in my life before I finally performed it. The programmes were announced and being publicised, then at the last moment I didn’t feel I could do it with conviction: I remember thinking ‘Maybe I should’ve learned this piece when I was younger, or maybe I’m not old enough yet - but either way this isn’t the right time!’.

Sometimes you arrive at a first rehearsal thinking that you know what you're aiming for, but once you’re standing in front of an orchestra it just doesn’t work. The Scherzo of No. 5, for example, remains a tremendous challenge to this day: in fact Mahler himself wrote that he felt that for the next fifty years to come the movement would be massacred by conductors taking it too quickly! I feel a bit more comfortable knowing that. He’d conducted the premiere himself, of course, in Cologne - knowing the difficulties that movement still presents for us all over a century later, I cannot imagine how it must have been for those musicians having no point of reference other than the notes on the page and no idea where the music was going to go next!

There are so many tempo-changes, and for everything to flow properly you need to feel the progression of the whole movement. That’s what I tried to do that first time in Michigan, and I got through it: in fact after that concert the orchestra asked me to be their music director so I suppose it sounded convincing to them! The disappointing thing was when I came back to it a few years later and it didn’t feel as if it was flowing the way I wanted any more…

What special interpretative challenges does the Fourth Symphony present?

The Fourth Symphony sits quite apart from the rest of Mahler, which is often very monumental, because it’s essentially chamber music. In a sense you could compare it with Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony, which also sits slightly apart, and in fact Mahler’s Fourth IS very pastoral: there’s a lot of music relating to nature. There’s nothing ‘in your face’ about it, which presents a different kind of challenge to something like the Second Symphony (and so many others). It took a long time before I dared to conduct it: it’s like having a very precious object that you’re afraid to touch in case you break it, and that’s what kept me away from the piece for many years. The first time I conducted it was with the Orchestre de Paris, in the 1990s.

Given Mahler’s own Bohemian roots, do you feel a particular affinity between the Czech Philharmonic and this music?

Those roots are the reason for making these recordings. People almost never think of Mahler as a Czech composer and musician, they see him as entirely Austrian – but even if you didn’t spend a long time in your birthplace, those roots from your early years are far more powerful than many imagine. And in Mahler’s case that’s what happened: everything started in Bohemia.

And the Czech Philharmonic is an orchestra which is so much based on its roots: to give you an idea of how far the tradition stretches back, we are now 126 years old, and the first concert that the orchestra ever gave was conducted by Dvořák! At present we have a Japanese flautist and a Spanish double-bass player, but essentially it’s a Czech orchestra. Historically that was because of the political situation and the lack of contact with Western Europe during the Cold War period - but after the Wall came down and it became essentially a country that was integrated in Western Europe that side of things didn’t change.

And that isn’t motivated by any kind of chauvinism or lack of willingness to accept players from abroad - it’s simply because there is such a phenomenal crop of young Czech musicians. Year after year we see the most amazingly gifted and musical players coming through our Czech Philharmonic Youth Orchestra, so it’s only natural that the very best of them realise their dream of entering the main orchestra, and in a way that protects the orchestra’s unique identity.

In a sense I think that Czech people - all of them - are born musicians . A small number become professional musicians and others go on to do something else in life, but they are all really musical: they need it viscerally, and it’s connected to the genetics of the nation. When I became their Music Director and decided that a Mahler cycle would be next after our Tchaikovsky project, I knew of the Czech Mahler tradition – the Czech Philharmonic last recorded the cycle with Václav Neumann about thirty years ago, but there are very few members of the orchestra who played on those recordings so I was curious whether it would still feel like home ground…

We opened the season with the Second Symphony, and from literally the first minutes of rehearsal I knew that it was a natural sound-world to them: their sensibility and the kind of sound that they produce is just ideally suited to Mahler’s music and to Czech music. Thanks to the musicality of these artists, they are able to transcend their national borders – if they play French music, to me it sounds absolutely spiritually authentic, as do Brahms, Strauss, or Shostakovich. But Mahler happens to be their home territory, and I think that comes across.

You mentioned that very few players from the Neumann cycle are still around - is the Czech Philharmonic a relatively young orchestra?

Fortunately we have a real mix, and that’s very healthy. Problems can arise when all your players are roughly the same age, because it means they all retire around the same time and new players all arrive at the same time - that creates a very delicate period of adjustment, which is tough and can last for years. Take the Berliner Philharmoniker: at the end of Karajan’s life it was essentially an old orchestra of colleagues who’d lived together for years, and then when Abbado was elected it suddenly became a kindergarten! The new players had phenomenal individual virtuosity, but because they all came from different countries and schools, they didn’t necessarily think the same way about phrasing and everything else it takes for an orchestra to gel. Today they sound absolutely organic, but it took a long time. It’s something that no-one can control, and in Prague we’re very lucky that somehow it’s well balanced.

Did pandemic restrictions play a part in the decision to launch the cycle with No. 4, given the small forces involved?

No, that was entirely an artistic decision. The original idea was to release Symphony No. 2 first, and certainly No. 4 isn’t spectacular; it isn’t a guaranteed standing ovation like No. 2, where the final stretch will send people into a state regardless of what’s happened before! But there was just something special in the air when we were playing and recording No. 4, and I sensed it again when we were listening and editing, so here we are…

We were very fortunate during the pandemic for several reasons - not least because in the European system orchestras are state-subsidised, so the musicians continued to be paid their salaries regardless of whether or not they could perform. Of course there were some points when we couldn’t play in front of a live audience, or when we had to change programmes at short notice to accommodate social distancing restrictions on stage - but we were prepared to be as flexible as possible to stay present in the life of the community. Technology helped, because like the Berliner Philharmoniker and their Digital Concert Hall we had all the necessary people and equipment on hand to live-stream performances in high quality.

I know a lot of people think it must be very strange to play in an empty auditorium, but to me it’s just the same as making a recording – the only difference is that for streamed performances we wear stage-clothes! We did a lot of it, and it was amazing to see the messages coming through on social media from Zimbabwe, Mexico, Guadalupe, France, America…Because everything was accessible we attracted audiences from all around the world, and you realised how much it meant to people during the times when they couldn’t be together: in moments of genuine crisis, the need for spirituality and for art grows enormously.

Chen Reiss (soprano), Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Semyon Bychkov

Available Formats: CD, MP3, FLAC, Hi-Res FLAC